January Again: The Biennial Panic

It’s January, and it is already time for me to start making belated plans for fulfilling my continuing education requirements. I’m not sure what’s wrong with me, but this happens every two years. I put it off and put it off month after month until I really have to hustle to fulfill the requirements. This is complicated, expensive, and time-consuming for me, and I imagine the same is true for many of my fellow board-certified forensic psychologists. I know many of us are licensed in multiple states with different CEU requirements. In my case, I am licensed in New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Virginia. My dates for reapplying are all different from state to state, and the requirements differ as well; some require specific numbers of ethics units, and a couple have special requirements for topics such as domestic violence or diversity. The most difficult state is Vermont, which requires 60 CEUs every 2 years. Vermont makes the process particularly difficult because of the way they allocate how different kinds of CEUs can be used to satisfy their requirements.

Vermont: An Exercise in Regulatory Math

The most demanding state, by far, is Vermont, which requires 60 CE hours every two years. Vermont also has opinions about how those 60 hours should be obtained. At least 6 hours have to be specifically devoted to professional ethics. The rest must be divided among three buckets: large group activities, small group activities, and individual activities.

Large group activities are what you probably picture when you think “CE”: formal courses, in‑person lectures, conferences, workshops, symposia, webinars—anything where a lot of us sit in the same (actual or virtual) room while someone with slides talks at us. At least 24 of the 60 hours must come from this category, which in practice means about four full‑day workshops.

Small group activities are defined as in‑person or video meetings of 3 to 8 professional peers. These have to be preplanned and involve something plausibly scholarly: discussing current issues in psychology, talking about practice, doing case consultation or supervision, or even a journal or book club.

Individual activities are things many of us already do as part of normal professional life: independent reading, online CE courses, writing papers, preparing talks, conducting scholarship or research, keeping up with journals, or even critically reviewing “alternative paradigms” in psychology. There’s no minimum here, but there is a cap: no more than 24 of the 60 hours can come from individual activities.

Now let’s run the numbers. I have to get 24 live large‑group hours—that’s roughly four full‑day workshops. I can get another 24 hours from individual work like writing, research, and self‑study. That puts me at 48 hours, which still leaves me 12 hours short.

In theory, those 12 hours could come from small group activities. But the rules are vague about how many small‑group hours I can actually apply, and how exactly things like ongoing group supervision will be treated. Maybe they’d all be approved; maybe some would; maybe I’d end up in a bureaucratic argument about whether my consultation group was sufficiently “pre‑planned.”

The safer option is just to book another workshop or two and resign myself to another 12 hours in a lecture hall or parked in front of my laptop. That is a lot of time to spend passively absorbing information I could probably access more efficiently with a stack of articles and a pot of coffee.

The Fiction That “Live Is Better”

But let’s step back for a moment. How did we end up deciding that sitting in lectures is a necessary, even privileged, way to prove we’re keeping up with the field? We’re supposed to be a science‑based profession; that’s why we spent all those years earning Ph.D.s and Psy.D.s. Surely somewhere there must be a tidy stack of randomized controlled trials showing that live CE is clearly superior to reading, self‑study, or recorded courses.

Alas, no. When you look at the literature, including Cochrane‑style reviews of educational meetings and workshops, you mostly find that these activities can produce small improvements in provider behavior, with a lot of variability and a general inability to say which specific formats are actually better. There is no solid evidence that the kind of live, large‑group hours favored by many boards are uniquely effective compared to other ways of learning. The usual selling points—“You can ask questions! You can network! You’ll feel more confident!”—are more marketing copy than outcome data. Yet, every year, we dutifully trundle off to workshop after workshop as if this were self‑evidently the gold standard.

And it gets better. Most live workshops don’t require you to demonstrate that you actually learned anything. You sign in, sit down, and as long as you don’t flee the building, you get your hours. In theory, I could spend six hours playing Stardew Valley on my tablet while the presenter explains the latest “innovations,” and I would still leave with a shiny certificate. I would consider that a tragic misuse of both time and farming simulation, but the system would be perfectly satisfied.

Online and streaming workshops often include post‑tests, which sounds like an improvement—until you realize that in most cases, the answers are either sitting right there in the PowerPoint or are so transparently obvious that you could pass without having paid any attention. A typical question might look like this:

When doing internal family therapy, which is the most correct?

A. Establishing rapport

B. Understanding the client’s mental map of their family dynamics

C. Finding out their favorite NFL team

D. Both A and B

If you can’t guess that the answer is D without having listened to a single minute of the workshop, you probably shouldn’t be licensed in the first place. These “assessments” function more as a compliance checkbox than as any meaningful measure of learning or retention.

For early‑career psychologists or people shifting specialties, a good workshop can be genuinely useful. The trouble is that many seasoned clinicians already have established areas of expertise. Mine happen to be forensic psychology and forensic neuropsychology. There are fewer high‑quality CE offerings in those subspecialties, and while remote options have helped, they are not cheap.

Live, lecture hall CEU offering cost anywhere from $100-$300 per hour. If I tried to get all 48 of my Vermont‑eligible hours that way, I’d be looking at something in the neighborhood of $4,800 to $14,000 and that’s before adding travel and hotels if the event isn’t local. That’s a substantial investment for the privilege of sitting in a room being talked at, especially when I could access the primary literature for free or nearly free and tailor my reading directly to the questions that come up in my practice.

Cost, Relevance, and the Specialty Problem

Another option is to sign up for cheaper alternatives, but that usually means spending a day in trainings that have little to do with my practice and aren’t necessarily much cheaper. I could, for example, sit through an entire day on nutritional treatments for autism. A quick trip to PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library, however, already tells me that most “alternative” nutritional interventions for autism are backed by low‑quality studies and show little, if any, reliable treatment effect. Why would I pay good money to hear someone summarize weak evidence I can read myself in an hour?

Some of these programs are perfectly reasonable for a psychologist who is just starting out or wants a basic refresher on a topic. The problem is the long trail of offerings I’d happily skip, especially those with titles like “Healing the Wounded Inner Child,” “Polyvagal Pathways to Everything,” or “Internal Family Systems for Your Dog, Your Neighbor, and Your Mailman.” If it were crunch time and I still needed 12 CEUs, though, I might find myself eyeing them anyway.

That doesn’t sound so terrible at first glance. It’s not hardcore forensics, but surely I could still learn something, right? Maybe—but maybe not. A lot of these offerings drift into the realms of pseudoscience or what has been memorably called “tooth fairy science.” Tooth fairy science is doing careful, even statistically sophisticated research on a phenomenon whose existence has never been established in the first place, so the work can’t actually answer the question it claims to address.

A classic example (from Harriet Hall, who coined the term) is studying the Tooth Fairy herself: you might compare how much money is left per tooth in different families, whether first teeth get higher payouts, or whether putting the tooth in a plastic baggie vs. wrapping it in Kleenex affects the amount. You could get clean data and significant effects, but you still haven’t shown the Tooth Fairy exists—so you’ve done tooth fairy science rather than answering the real underlying question.

Pseudoscience vs. Tooth Fairy Science very briefly:

- Pseudoscience: Methods ignore or violate basic scientific standards; data are often anecdotal, uncontrolled, or cherry‑picked; progress is minimal because ideas don’t change in response to contrary evidence.

- Tooth fairy science: Sometimes rigorous methods, but aimed at the wrong question; the core premise is untested, implausible, or false; sophisticated work proceeds without ever establishing that the underlying entity exists at all.

In other words, you can run elegant statistics and publish in peer‑reviewed journals, but if you’ve never stopped to ask whether your “tooth fairy” exists in the first place, you are just doing sophisticated work on a nonexistent problem.

When Pseudoscience Earns CE Credit

Of course, some ideas and practices in psychology and related fields manage to be both pseudoscientific and classic tooth fairy science at the same time. My favorite example is craniosacral therapy. In this approach, the practitioner palpates and presses on the patient’s skull. John Upledger, D.O., proposed in the 1970s that the cranial sutures of the adult skull don’t fully fuse and that trained practitioners can feel a special energy‑like pulse in the cerebrospinal fluid that can become dysregulated. By gently manipulating the skull, they claim to restore these supposed pulsations to their proper state and thereby improve a remarkable range of conditions, including autism, seizures, cerebral palsy, headaches, dyslexia, colic, and asthma.

Where to even start? Adult cranial sutures do not move in any clinically meaningful way, and certainly not enough to be realigned by light hand pressure. Cerebrospinal fluid does not emit a detectable “energy pulse,” and when researchers have tried to test inter‑rater agreement on the alleged craniosacral rhythm, practitioners can’t even consistently agree on what they’re feeling. Systematic reviews of craniosacral therapy have repeatedly concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support specific therapeutic effects beyond placebo, with high risk of bias and no clinically meaningful improvements in pain or other outcomes when better‑designed trials are considered. In other words, we start with a biologically implausible premise, layer on untestable “energy” language, and then add low‑quality studies that never seriously grapple with whether any of this is real.

On a certain level, you almost have to admire it. As a piece of snake‑oil design, craniosacral therapy is impressively complete: a mysterious mechanism, sweeping claims across multiple conditions, emotionally compelling anecdotes, and just enough scientific‑sounding language to keep the skeptical part of your brain slightly off‑balance. If I had set out to invent the perfect modern placebo treatment, I’m not sure I could have done better on my best day.

And at this point you might reasonably protest: “But surely the APA—a proud guardian of science, empiricism, and evidence‑based practice—would never let this kind of thing into the CE ecosystem, right?”

I wish that were the case. Unfortunately, even within APA‑approved continuing education, you can find offerings that range from conceptually shaky to full‑blown pseudoscience.

Take Thought Field Therapy (TFT) for agoraphobia. TFT, developed in the 1980s by Roger Callahan, starts from the idea that emotional disturbances are caused by disruptions in “thought fields,” which supposedly behave like energy fields in the body. The proposed fix is to tap on specific sequences of acupuncture points to correct these invisible energy disruptions. A few obvious questions come to mind:

- Have these “thought fields” or even the underlying energy meridians ever been demonstrated with any kind of scientific instrument? No.

- If I just ask a patient to tap on themselves in random places, might they still feel a bit better? Quite possibly—but that’s exactly what you would expect from non‑specific factors and placebo effects, not from tuning imaginary energy lines.

This is tooth fairy science in its pure form: elaborate protocols, precise tapping sequences, and plenty of charts, all built on top of entities that have never been shown to exist. Why would APA approve continuing education credits for this kind of thing? I don’t have a satisfying answer. I will simply note that becoming an APA‑approved CE provider involves, among other things, paying fees and navigating an application process that focuses more on format and documentation than on independently vetting every underlying theory.

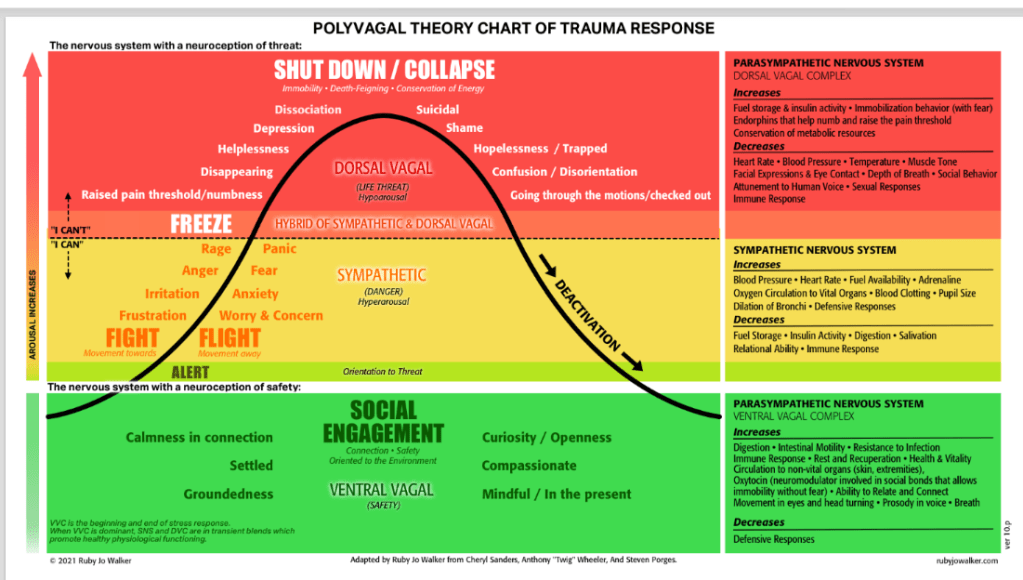

Polyvagal theory is a more subtle case, but its role in the CE ecosystem raises similar concerns. Stephen Porges’ model offers an evolutionary story about the vagus nerve, “neuroception,” and a three‑tiered autonomic hierarchy that is said to explain everything from shutdown to social engagement. Its appeal in workshops has less to do with robust clinical outcome data and more to do with how neatly it packages “the nervous system” into a narrative clinicians can graft onto almost any modality: your therapy isn’t just talking, it’s regulating dorsal and ventral vagal circuits.

The theory begins with a perfectly reasonable observation: the autonomic nervous system is deeply involved in how organisms respond to safety and threat. From there, it leaps to a much more ambitious set of claims—that mammals are organized around a strict three‑level autonomic hierarchy (ventral vagal social engagement, sympathetic fight/flight, dorsal vagal immobilization), that vagal “tone” and “neuroception of safety” drive most of our mental health and relational outcomes, and that therapists can directly modulate these circuits with polyvagal‑informed postures, breathing, or sound‑based protocols. Critics have pointed out that key anatomical and physiological assumptions are contested, and the clinical evidence base for these highly specific mechanisms is much thinner than the marketing would suggest, especially relative to the sweeping claims made in some CE offerings.

Here’s a sample:

Enter NeuroSomatic Alignment Therapy

But not all energy‐based approaches are without promise. I have recently developed one myself, integrating selected principles from traditional Chinese martial arts with emerging findings in neuroscience. The result is a modality I call NeuroSomatic Alignment Therapy (NSAT), which targets dysregulated mind–body fields through structured touch and brief, repeated “micro‑entrainment” rituals designed to restore adaptive coherence in the nervous system.

NSAT is grounded in the observation that chronic stress and trauma produce not only cognitive and emotional sequelae, but also persistent distortions in the organism’s underlying neuro‑somatic field. By combining slow, patterned contact at key transition zones (such as the cranio‑cervical junction and diaphragmatic dome) with precisely timed micro‑movements and breath cues, NSAT practitioners seek to re‑phase these dysregulated field segments. The goal is not simply symptom reduction, but a more global restoration of adaptive coherence across autonomic, interoceptive, and postural systems.

In clinical application, NSAT is delivered through brief, highly structured rituals that can be layered onto existing treatment frameworks without disrupting their theoretical orientation. Clients are guided to “map” regions of somatic static, then experience a series of short entrainment sequences in which targeted touch, breath pacing, and minimal voluntary movement are synchronized to foster a felt sense of internal alignment. Preliminary observations suggest that even a small number of sessions may enhance patients’ capacity to tolerate affect, modulate arousal, and experience their bodies as more stable, continuous, and responsive over time. NeuroSomatic Alignment Therapy™ (NSAT), © 2026 Eric G. Mart. All rights reserved.

Sound good? That’s unfortunate, because I just made all of that up. It’s nothing more than New Age woo‑woo wrapped in neuroscience jargon. Based on what I’ve encountered, though, I have no doubt I could market it—and in a couple of years you could probably receive APA CE credits for attending my workshop.

When Format and Career Stage Collide

For many of us who have been around awhile, the format itself is part of the problem. A good live talk can be informative and even entertaining, especially if the presenter knows how to hold a room. But I was first licensed as a psychologist in 1987, after several years working as a certified school psychologist, and in the four decades since then I’ve gotten reasonably competent at finding and digesting research on my own. I have full access to APA journals, and if something isn’t in that database, I can always drive over to the University of New Hampshire and raid their stacks.

It’s pleasant enough to hear an expert walk through something like the relative merits of the MMPI‑2 versus the MMPI‑3, but the truth is that I can usually get everything I need from the primary literature and a couple of good book chapters in a fraction of the time it takes to sit through a full‑day workshop.

So here I am again in January, staring down another CE deadline, calculator in one hand and registration website in the other, trying to assemble exactly the right mix of large‑group, small‑group, and individual activities to please five different boards. I’ll probably end up doing what I always do: a couple of solid workshops, some writing and self‑study, and maybe a slightly desperate ethics webinar when the clock is really ticking.

What nags at me isn’t just the hassle or the cost. It’s the mismatch between what we say we value and what we actually reward. We claim to be a science‑based profession, but our CE systems privilege seat time over demonstrated learning, format over substance, and occasionally pseudoscientific storytelling over careful engagement with the evidence. We make it harder to count the hours spent reading journals, writing, consulting with colleagues, and critically appraising new claims than the hours spent passively absorbing whatever happens to be on offer this year.

If CE Were Actually About Competence

If we really wanted CE to reflect how psychologists learn and maintain competence, we could make a few modest changes.

First, we could stop pretending that seat time is a proxy for learning. Instead of counting hours in chairs, boards could accept more structured demonstrations of learning: brief post‑tests, application exercises, or even short reflective write‑ups about how a training changed (or didn’t change) one’s practice. Nothing elaborate—just enough to distinguish “I was in the room” from “I engaged with the material.”

Second, we could give reading, writing, and consultation the respect they deserve. Many health professions have moved toward competency‑based continuing professional development models that explicitly recognize self‑directed learning plans, practice‑driven questions, and portfolios documenting how new evidence was integrated into practice. Psychologists could do the same: let a certain number of hours come from documented literature reviews, case‑based peer consultation, and scholarly writing, instead of treating those as second‑class, tightly capped “individual activities.”

Third, we could tighten the standards for what counts as “evidence‑based” in CE. That doesn’t mean banning anything that isn’t backed by ten randomized trials. It does mean asking sponsors who offer grand mechanistic stories—about energy meridians, thought fields, or exquisitely tuned vagal ladders—to clearly label where the evidence ends and speculation begins, and to justify their claims with something more than testimonials.

Finally, we might acknowledge that different stages of a career call for different kinds of CE. Early‑career clinicians may benefit from more structured, curriculum‑like workshops; seasoned specialists might justifiably lean more on targeted self‑study, advanced case consultation, and focused updates in their subspecialty. A one‑size‑fits‑everyone‑for‑60‑hours‑every‑two‑years system serves neither group particularly well.

Until then, I’ll keep playing the CE shell game like everyone else—while quietly wishing we’d apply even half as much critical thinking to our own requirements as we ask our clients to apply to their treatment choices.

O

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.