Whenever people ask me what I do for a living, and I say that I’m a forensic psychologist, I generally get some version of “Oh, that must be so cool!” I get it; the only exposure most people have to the professions is what they see on “L.A. Law” or “CSI.” Generally, they see a “forensic psychologist” survey a crime scene and determine that the perpetrator of the murder was a Gen Z male with dyslexia, a slight limp, and a predilection for Chicago blues played on the original vinyl. Unfortunately, it’s not an actual thing. The FBI uses behavioral consultants, and I assume they must be helpful, but I’m given to understand that they are only used in specialized circumstances. The reality of the profession is very different.

The latest crop of forensic psychologists generally follow a fairly straightforward path: four years of undergraduate study, four more in graduate school—typically in clinical, counseling, or school psychology, sometimes with a forensic concentration. Then comes a forensically oriented internship, and you’re good to go—or at least that’s how it sounds when I oversimplify it. Back in 1987, when I got started, things weren’t quite so streamlined. I had gone through a school psychology program. I’d applied to several graduate programs in psychology and landed on the “please reapply next year” list at a couple of them. With a year to fill, I spent about six months working on an acute psychiatric floor at University Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. That was instructive—but six months was plenty—so I headed back down to Sarasota, Florida, and moved in with one of my best friends and my girlfriend at the time. You can probably guess where that part of the story is heading, but perhaps that’s for another post.

During this time, my mail was going to my family home in Beachwood, Ohio. My father monitored the letters as they came in. He generally threw the bills away unopened, working on the theory that they would always send another if you missed one. That caused me some problems down the road, since some of those “bills” were notices that it was time to start repaying my student loans. I ended up in default and had to move heaven and earth to get that straightened out.

However, my father did open one of the letters: it was an invitation from Yeshiva University to reactivate my application for the coming academic year. He decided that was a good idea, forged my name on the application, and sent it off. He never mentioned this to me at the time. A bit later, he called to let me know that I had been accepted to a school to which I didn’t quite recall having reapplied.

Ok, here’s the short version of what happened after I got my doctorate. My wife and I bounced around a bit but finally settled in Concord, New Hampshire. I worked in the schools for a couple of years and then started a private practice. I saw some adults, a few couples, and lots of obstreperous adolescents.

In the course of my work, I got to know Wilfrid Derby, Ph.D., who was board certified in clinical and forensic psychology. I remember him telling me, in that booming naval officer voice of his, “You should start taking some forensic cases.” I replied, “Sure, why not? What is forensic psychology?” Thus are careers launched.

So, if forensic psychology is not mostly about profiling serial killers, what is it? It might help to give a little background. Most people seem to associate the word “forensic” with dead people, probably because they only hear the word in connection with autopsies. That is not quite right.

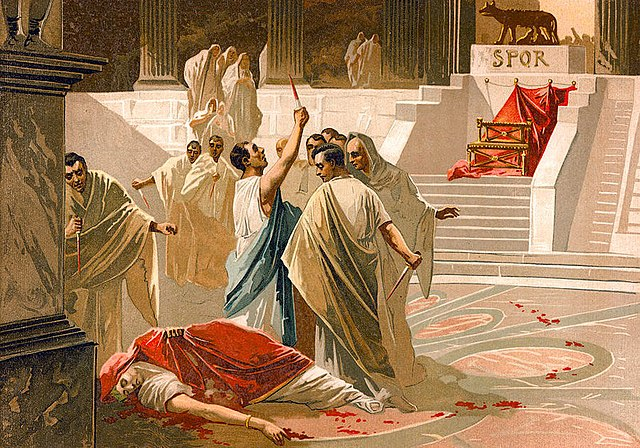

The word “forensic” comes from the Latin forensis, meaning “of or pertaining to the forum.” The Roman Forum was where the courts met. On the Ides of March in 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was assassinated, and a physician was called to examine the body. Antistius, a medicus (Roman physician), found that Caesar had been stabbed 23 times, but only one of the wounds was fatal. He determined this by probing the wounds with a glass rod and discovering that only one of them, located below Caesar’s left shoulder blade, was deep enough to reach vital organs and cause his death. In a way, that makes Antistius the grandfather of forensic science.

In American courts, there are two types of witnesses. Let’s say you are walking down the street and you look up just in time to see a car hit a man who is crossing the street. The police arrive and take your statement, and several months later you are called to court to testify. For the sake of this example, you do not have any special knowledge of cars, road conditions, or motor vehicle accidents. That means you are being called as what is known as a lay witness. You can talk about what you saw, heard, or actually said yourself. You cannot testify about your estimate of the speed of the car, the road conditions, or whether you thought the driver had been reckless. Why not? Because you do not have any special knowledge that would make your opinions on these topics any more useful to the judge and jury than anyone else’s.

The other type of witness is referred to as an expert. Here in the U.S., we have the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) that lay out the rules for federal trials. Most states have their own “rules of the road” for trials and procedures that pretty much follow the FRE. Rule 702 of the FRE defines what makes someone an expert for the purposes of the court:

- The expert’s scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact understand the evidence or determine a fact in issue.

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data.

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods.

- The expert’s opinion reflects a reliable application of these principles and methods to the facts of the case.

So you have to know what you are talking about in a specialized area that the judge and jury would not be expected to know much about (for example, whether the car was going too fast to be able to stop). Not just that, but the way the expert arrived at their conclusion has to be based on solid research that they actually applied to the situation at hand.

Quick digression: I recently read Christopher Hitchens’s autobiography, Hitch-22, in which he includes this joke. A Buddhist monk walks up to a hot dog stand and says, “Make me one with everything.” The vendor fixes him a hot dog, and the monk pays with a twenty-dollar bill. He waits, but the vendor shows no sign of giving him his change. Finally, the monk asks for his money, and the vendor sighs and says, “Alas, change comes only from within.”

But you do not need an advanced degree to be an expert. Here is an example I sometimes use when I give talks on this subject. In a town not far from Chicago, there is a company that has a number of hot dog stands in different parts of town. Unfortunately, one of their customers buys one with everything, gets food poisoning, and dies. Sadly, in this case, the only change involved was a wrongful death suit.

The family of the food-poisoned customer (the plaintiffs) sues the owner of the stand for damages. They bring in several experts to testify. One of these is the M.D. who performed the postmortem examination and determined that the unlucky patron died of E. coli, most likely from the hot dog. They also bring a second witness. This witness comes from New York, where his family owns and runs over 50 hot dog stands. He is prepared to testify about industry standards regarding sanitation: how often cleaning should be done and what agents should be used. Even though he does not have an advanced degree of any kind, the court rules that he is an expert and can testify to his opinions. He has experience and technical knowledge that the judge and jury cannot be expected to have, and his testimony about how hot dog stands should be maintained will be helpful in the trial.

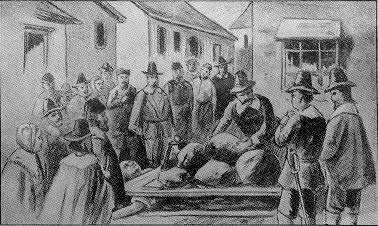

The point of all this is that forensic psychologists serve as experts for the court. They have one foot in the world of applied psychology and one foot in the world of law. For example, one type of evaluation forensic psychologists commonly perform for the court is an assessment of competence to stand trial. Again, a little background. In the Middle Ages, people put on trial had to consent to be tried “by God and my country.” “Consent” meant something a bit different back then: if you did not “consent,” they might throw you into some horrible prison cell or place you between two large pieces of wood and pile them with stones until you felt like “consenting.”

Courts eventually noticed that some defendants truly could not speak or hear and were thus “mute by visitation of God,” while others were “mute of malice,” stubbornly refusing to participate. Over time, the “visitation of God” idea broadened into a more general recognition that it is fundamentally unfair to try someone who cannot understand what is happening in court or communicate with counsel, because it is essentially like trying them in absentia. That tracks a basic intuition: you cannot meaningfully confront your accuser if you do not understand who the accuser is, what you are accused of, or what the process is about.

Weighing the odds of acquittal against the risk of a long sentence, while factoring in suspended time, probation exposure, and the misery of several years in prison, requires holding multiple contingencies in mind and engaging in fairly complex cost–benefit reasoning. Most defendants can handle this with help from counsel, but some cannot—because of very low intellectual functioning, major mental illness, serious brain injury, or a combination of these. On top of that, a nontrivial number exaggerate their symptoms or malinger, which is precisely why courts rely on competency evaluations to sort out who is genuinely incompetent from those who are not.

But courts gradually began to realize that there were some people who couldn’t hear or talk. These people were said to be “mute by visitation of God,” while the stubborn ones who needed to be squished between two boards were “mute of malice.”

As the law developed over time, the idea of “mute visitation of God” was expanded. The idea was that it was fundamentally unfair to try a person for a crime if they didn’t understand the process of a trial and couldn’t communicate with their lawyer, because it would be like trying them in absentia. Makes sense, really; how can you confront your accuser if you don’t understand who the accuser is or if you really don’t understand what you have been accused of?

What if you are offered a plea bargain? You are accused of aggravated assault, but the prosecutor is not sure they can make it stick. So he tells your lawyer that he will let you plead guilty to simple assault and get two years of probation. But you already have a suspended sentence for a previous assault with three years of incarceration hanging over your head. Your lawyer tells you that you could go to trial and you have a decent chance of being found not guilty, but if you are found guilty, they will really bring down the hammer: you will get the three years you were facing for the aggravated assault, plus the three years that were suspended. They might also tack on some additional time for violating your probation.

Weighing the odds of acquittal against the risk of a long sentence, while factoring in suspended time, probation exposure, and the misery of several years in prison, requires holding multiple contingencies in mind and engaging in fairly complex cost–benefit reasoning. Most defendants can work this out with help from counsel, but some cannot—because of very low intellectual functioning, major mental illness, serious brain injury, or some combination of these. On top of that, a nontrivial number exaggerate their symptoms or simply malinger, which is why courts order competency evaluations in the first place: to sort out who is genuinely incompetent from those who are not.

Most people can work this kind of thing out, and you do have a lawyer to help you in a criminal trial. But some defendants cannot, for several reasons. Some have very low IQs, some suffer from major mental illnesses, and some have had serious brain injuries. Also, there are a significant number of folks who exaggerate their symptoms or simply malinger. So how does the court determine who is really incompetent versus those who are not?

That is where forensic psychologists come in. When I or one of my colleagues receives a referral for a competency evaluation, the first thing we do is review any available medical and educational records. We want to know whether the defendant had any of these problems before they were arrested, back when they had no motive to exaggerate their symptoms. It is also important to gather as much information as possible about what other doctors have thought about them. Sometimes the records show problems the defendant did not acknowledge on the personal history form they filled out that may have a bearing on the case; for example, they may have neglected to mention a long history of polysubstance abuse. Other times, you might discover that although they cannot recall what the job of the judge is in a jury trial, no matter how many times you tell them, their hobby is chess and they have won several recent local tournaments. That does not make them competent, but it is something to keep in mind.

There is a general protocol for determining competence across the various capacities psychologists assess, laid out by Thomas Grisso, one of the leading figures in modern American forensic psychology. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Grisso

This is simplified, but here is how it goes.

Functional component: Can the examinee do what we are asking them to do? Do they understand what is involved in making a will, signing a contract, standing trial, or making medical decisions? This part is similar to when you took your driving test at age sixteen: they gave you a minute to parallel park, and you either could do it or you could not.

With a competence-to-stand-trial assessment, you ask whether the defendant knows the jobs of the judge, jury, prosecutor, and defense attorney. Do they know that they have to be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, and what that means? Are their choices about what to do in their present situation rational? It is one thing to be cynical about the U.S. justice system if you are a member of an oppressed minority; it is different if you believe that your lawyer, the members of the jury, and the bailiffs are werewolves and vampires.

All of this tracks the legal standard for being able to stand trial: a defendant is competent if they (1) understand what they are charged with and what the court process means for them, in a real-world, rational way, and (2) can work with their lawyer well enough, right now, to help defend the case.

If the defendant has no problem with the functional component of the assessment, that is usually it. You ask them pertinent questions about standing trial and their view of the process, and they give satisfactory answers. But what if they cannot? What if they think they can plead guilty but still argue that they are innocent? Or that the jury decides guilt based on a simple vote and the majority wins? You might assume they were just uninformed and explain the facts, but what if they still do not understand?

That brings us to what Grisso calls the causal component: what is the reason for these apparent difficulties? That is really where the rubber meets the road in these evaluations.

There could be a number of reasons:

Maybe they have low intellectual ability. You look at the records and discover that the defendant was in special education starting in fifth grade. School testing indicated an IQ of 73, placing him around the third percentile compared to his classmates. He was also evaluated by the speech and language pathologist and had particular difficulty understanding spoken language. That might be the problem—and he had it long before he committed any crimes.

They might also have a history of serious mental illness. The record shows that he sees a provider at the local mental health center and is prescribed medication for schizoaffective disorder, which is something like a combination of psychosis and bipolar disorder. He does reasonably well when he takes his medication, but he has a history of not taking it. That has led to problems in the community and, at times, psychiatric hospitalization. This raises the possibility that his difficulty with the issues associated with standing trial is related to mental illness.

Another possibility is that he is playing up his problems, or malingering. It happens all the time. Maybe while he was being held at the county jail before being released on bail, another inmate told him that if you act really confused or claim you just cannot understand things, the court will find you incompetent to stand trial and cut you loose. This is not an all-or-nothing proposition; you can exaggerate your problems a bit, pretend you do not understand anything, or do something in between. Forensic psychologists might suspect this for many reasons, which then shapes how they approach the rest of the evaluation.

Their history might be inconsistent with their presentation. For example, they may pretend not to know A from B or 1 from 2, but it turns out they pay their own bills, handle a checkbook, and drive a car. They might claim to have amnesia for the events surrounding the alleged crime, yet offer a detailed account of the specific things they supposedly do not recall. Or the unit staff notes may describe the defendant as oriented and social, watching complex television shows and playing poker with other patients or inmates, while in the interview room the same person stares blankly and insists they cannot understand simple questions like, “Why are you here today?”

There are more clinical indicators, but you get the idea. In one case, I was evaluating a young man who had some learning problems but who also professed an almost complete lack of understanding of the process of standing trial. He answered nearly every question with, “I don’t know; I’m confused.” Spoiler alert: people who are truly confused almost never keep repeating, “I’m confused.”

After about half an hour of this, I suggested we take a break and asked what he liked to do in his free time. He told me he liked to play basketball and that he was pretty good. I said I had never really played and did not understand the rules. He proceeded to explain them, including traveling with the ball and spending too much time in the key. He knew there were five players per team and that the referee enforced the rules but did not play for either side. He could explain the difference between a personal and a technical foul, but he could not tell me the difference between simple and aggravated assault, even after I explained it several times. That did not prove he was competent, but it made me suspicious—and it meant I needed to dig deeper.

One of the ways psychologists gather evidence that a defendant may not be trying, or may be presenting themselves as more impaired than they really are, is through performance and symptom validity measures. These tools are designed to flag exaggerated or noncredible symptoms without revealing exactly how they work.

With performance validity tests, you check whether the defendant is playing up intellectual deficits. You do this by giving tests of memory and attention that look difficult to a layperson but are actually very easy. For example, you might read a list of words and ask the defendant to repeat them back, then note how many they get right. In some cases, you may find that they remember fewer words than eight-year-old children with intellectual disabilities or people over eighty with moderate dementia. That pattern strongly suggests they are not trying very hard—or are actively trying to look bad.

The process is similar when checking the validity of reported psychiatric symptoms. There are reliable differences between how people with genuine psychosis present and how people who are pretending tend to present. Some patterns that raise suspicion include:

- Exaggerators and fakers may describe their illness as starting all at once: one day they were fine and the next they were hearing voices and seeing things

- They may report hallucinations that go on 24/7, with no breaks and no way to distract themselves. That is not how hallucinations typically work in real psychosis

- They may endorse every possible psychotic symptom as occurring all the time: hearing voices, seeing visions, feeling things crawling on them, smelling invisible poison gas, all at once and constantly. Again, that pattern does not line up with how actual psychotic symptoms usually present.

The tests psychologists administer look at the same kinds of patterns, but they also generate scores that show just how far the person’s reported symptoms deviate from what is typically seen in people with actual psychosis. When someone scores in a range that is markedly more extreme than genuine patients, that is a red flag that exaggeration or feigning may be part of the picture.

One wrinkle that complicates things is that people with very real, severe mental illnesses can sometimes exaggerate their symptoms and make them look worse than they really are. In those cases, they may, in fact, be incompetent—but the exaggeration makes it much harder to sort out what is genuine and what is being played up for effect.

So at this point, you have a functional assessment and some hypotheses about why any apparent problems are showing up. The next thing to consider is what Grisso calls the interactive component.

The idea behind this component is that some kinds of cases are more complicated for defendants than others. A case involving a fight over a pack of cigarettes is pretty simple; standing trial as an accessory in a drug-distribution case, with multiple co-defendants giving conflicting testimony and very complex legal issues, is a lot harder for a low-functioning defendant or someone with psychosis or brain damage. The forensic psychologist has to factor these variables into the conclusions.

Next comes the conclusory component. This is the report’s “bottom line,” where you tell the court whether you think the defendant is fit to stand trial. This part of forensic reports has generated considerable controversy in forensic circles. Lawyers and psychologists refer to this as the “ultimate issue”—the very question the court is trying to decide. Examples of ultimate issues include questions like

- Was the defendant legally insane at the time they committed a crime?

- Did Grandpa know what he was doing when he disinherited his kids and gave all his money to the Church of the Blinding Light?

- Was the defendant coerced into confessing by the police?

On one side are those who argue that psychologists and psychiatrists should not be the ones to answer the ultimate legal question—things like “Was this person legally insane?” or “Is this parent fit to have custody?”—because those decisions belong to judges and juries and necessarily involve moral, legal, and value judgments as well as psychological data. On the other side are those who contend that, in practice, courts need clear, plain‑English answers that explicitly connect the findings to the relevant legal standard, as long as the evaluator carefully lays out the supporting data, the inferential steps, and the important limitations so the court can see that this is an opinion, not a pronouncement.

If you subscribe to the idea that you should not give an ultimate-issue opinion, the goal is to provide a detailed description of what the defendant could and could not do when you assessed their abilities and then let the court decide what that means in relation to the legal standard. I tried that a few times, always with the same result.

As an aside, when I first started testifying in court, I did not know that the judge could ask you direct questions; I thought only the attorneys could do that. The first time a superior court judge turned to me and said, “I have a few questions, Dr. Mart,” I almost jumped out of my skin. This work is full of those kinds of surprises.

Many years ago, I went down to North Carolina to testify in a case and did not realize it was high profile, at least locally. The bailiff came to the little room where I was waiting and told me, “You’re on.” I walked into the courtroom, and it was a circus—reporters, photographers, several video cameras, the jury, and a couple of alternates. I remember thinking that if I had known, I would have worn a better suit. But as usual, I digress

The point is that every time I refrained from giving my opinion, the judge would turn to me and ask, “So, Doctor, do you think the defendant is competent to stand trial?” My conclusion is that judges know they get to make the call; they just want to know what you think. Over the years, I have tried to address this by adding something like the following to my reports: “While decisions about the ultimate issue in these matters rest with the court, it is my opinion that (defendant) is/is not competent to stand trial.” This way, I signal that I know who is in charge and still provide the opinion they want to hear.

There is a further wrinkle. As an expert, you are almost always asked, “And do you hold this opinion to a reasonable degree of psychological certainty?” The problem is that nobody seems to know exactly what that means. The phrase “reasonable [scientific/medical] certainty” has no clear scientific definition and has been criticized for being vague and potentially misleading. I generally take it to mean, “As a psychologist, are you pretty sure?” but opinions differ. One of my colleagues caused a minor uproar by replying, “If you tell me what you mean by that, I will tell you if I do.” Another colleague was asked if he held his opinion to a reasonable degree of psychological certainty. He said yes and was then asked what he thought that meant. He replied, “I am reasonably sure that I am probably right.”

The last component is called the remediative component. In plain English, this part asks, “Can anything be done to improve the defendant’s understanding of the process?” In many jurisdictions, judges can find a defendant “incompetent but potentially restorable.”

If the main problem is that the defendant has a severe mental illness and stopped taking medication, that may be relatively straightforward to address. If the problem is simply not knowing the pertinent information, the federal system and many states have competency restoration programs that combine legal education with treatment; sometimes that helps, and sometimes it does not. After these steps are tried, the defendant is assessed again. If they are ruled competent, the case goes back to trial. If not, they are typically released or, in some states, can be civilly committed for psychiatric care and monitoring instead of remaining in the criminal process.

That is the forensic assessment of competence to stand trial, in broad strokes. CST is a good place to start because it pulls together many of the basic concepts that show up in other types of forensic evaluations. On a certain level, it reminds me of being a bartender. A martini is gin or vodka with a bit of dry vermouth. Once you master that, a Manhattan is pretty much the same thing but with bourbon and sweet vermouth. The same goes for a Martinez (Old Tom gin and bitters) or a Vieux Carré (rye whiskey and cognac with sweet vermouth and a couple of drops of Benedictine). Okay, it is more complicated than that, but you get the idea.

Of course, things are more complicated than what I have outlined here. There are often logistical hurdles just getting into a jail to see the defendant. Getting medical and arrest records can be difficult. Then there are the various maneuvers and general hijinks of the attorneys trying the case. But that is another post. For now, welcome to the world of forensic psychology. In future posts, I’ll talk about how these same ideas play out in insanity evaluations, juvenile cases, and custody disputes.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.