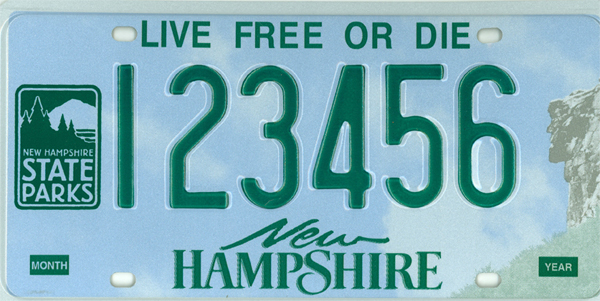

You may be aware that the state motto of New Hampshire is “Live Free or Die.” I once heard a comedian comment on this: “There’s a state that has had way too much coffee.” But you have to admire the sentiment; it’s right up there with “Give me liberty or give me death” and “It’s better to die on your feet than live on your knees.” And maybe I’m naive, but you’d think that the motto would set the tone for the state government. But at least in certain areas, alas, no. The New Hampshire Senate has put the kibosh on legalizing marijuana yet again. Their reasons?

- Sen. Bill Gannon, R-Sandown, the committee chairman, spoke at Tuesday’s committee hearing against HB 198, whose sponsors include Rep. Jonah Wheeler, D-Peterborough. Gannon said legalization would send the wrong message to kids, adding he never tried the drug himself because it is against the law. Well, Bill (can I call you Bill?), if you want to give it a try, you could always pop over to Maine, where it isn’t against the law.

- Gov. Kelly Ayotte: “I ran on this issue, and the people of New Hampshire know where I stand on it. I don’t support it. And “I don’t think legalizing marijuana is the right direction for our state. As we think about our fentanyl crisis, I’m concerned about the impact.” Also, “I know people are going to use marijuana. I just don’t think the state has to be in that business. It should not be in that business and that’s why I don’t support legalization.”

- Here’s my personal favorite from Stephen Scaer, Republican candidate: “Marijuana has the highest conversion rate to psychosis of any drug. Anyone who wants it can already obtain medical marijuana.” Granted, he lost his bid for state senator, but let’s digress for a moment.

What does “conversion rate” mean in this context? I assume he is talking about cannabis. The conversion rate would be the percentage of people who come to the ER with a cannabis-induced psychosis, which generally lasts from a few hours to a few days. These episodes are treated with reassurance, monitoring, and occasionally a dose or two of antipsychotic medication. Conversion refers to situations where these individuals develop a chronic psychosis. That’s a potentially serious problem. But how much conversion are we talking about?

- And Mr. Scaer is correct as far as his analysis goes. Here are the results of a large Danish study:

- Out of 6,788 cases of substance-induced psychosis, those with cannabis-induced psychosis had the highest conversion rate: approximately 47% eventually received a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, often within a few years of the initial psychosis.

- By comparison, the rates for other substances were:

- Amphetamine-induced psychosis: 30%

- Hallucinogen-induced: 24%

- Opioid-induced: 21%

- Alcohol-induced: 5%

But let’s remember that there are a lot more people who drink alcohol than use cannabis. You’d actually see more alcohol users developing psychosis than cannabis users.

That sounds grim, but what does it mean? The devil is in the details. It doesn’t mean that 47% of cannabis users will eventually develop psychosis. In reality, most population studies put the number at 0.1% of users over their life span. Also, these studies set the bar pretty low for what they consider psychosis Many include any episode of paranoia, hallucination, or disorientation as ‘psychosis,’ but most acute, brief reactions are not clinically significant or diagnosed as psychotic disorders. So when we talk about a conversion rate of 47%, we are talking about 47% of 0.1%. Let’s apply these numbers in a little thought experiment.

Let’s imagine that every adult over 21 years of age in New Hampshire started using cannabis moderately. That’s about 1 million people. Using a very liberal definition of cannabis-induced psychosis, we could expect to see about 27 cases per year. Of these, about 13 would eventually be diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder at some point in the future. Again, nothing to laugh at. But let’s remember that people who don’t use any intoxicants also develop these disorders. So what would we see if we looked at the absolute numbers of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia cases in both groups, the abstainers and cannabis users?

| Group | Schizophrenia | Bipolar Disorder |

| Abstainers | 4,000-10,000 | 20,000-44,000 |

| Cannabis Users | 4,100–10,200 | 20,100–44,200 |

Again, I don’t want to minimize the importance of even one case of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. But from a public health standpoint, these numbers mean very little. But back to New Hampshire and prohibition.

These legislators hold these positions in spite of overwhelming support for legalization. The University of New Hampshire conducts polls and found that over 2/3 of New Hampshire residents either moderately or strongly support legalization.

I think I should put this in context. As I write this, 24 states and Washington, D.C., have legal recreational marijuana. More have legalized medical marijuana. And New Hampshire is an island of prohibition surrounded by a sea of legal ganja. To the northeast, there is Maine, and to the west, there’s Vermont. Massachusetts to the south has recreational dispensaries. Let’s round out this picture: Connecticut and Rhode Island are on board.

Let’s be clear, intoxicants have downsides. I won’t rehash alcohol; we are all familiar with the problems associated with excessive use. Drunk driving fatalities, cirrhosis, delirium, and dementia. And cannabis is not completely benign.

It’s never a good idea to inhale large quantities of smoke from any source. The best thing to fill your lungs with is air; anything else is bound to have negative effects. I’m not surprised that heavy pot smokers have higher risks for respiratory and cardiovascular disease. And there has been a documented uptick in emergency room visits due to cannabis use. It’s a bad idea to get behind the wheel of a motor vehicle with altered consciousness from any substance. And if you get wasted on THC with your friends while playing video games, it’s probably not the time to operate a chainsaw or heavy machinery. Plus, there are cases where people develop reactive psychosis after getting high. So, are Governor Ayotte and Senator Gannon right to oppose legal cannabis?

I don’t think so. Where to start? Let’s begin with an analogy. At some point, self-driving cars will be a reality. And inevitably, one of them is going to malfunction and drive through a playground or take out a park bench and cause a number of fatalities. Just as inevitably, there will be a call for a moratorium on these cars. But what if (as predicted) self-driving cars actually reduce the risk of fatalities? Taking steps to stop their use in the face of one of these tragic events would be counterproductive and increase rather than decrease the average person’s safety. Life is full of these kinds of calculations. Let’s use a concrete example.

In most states, the speed limit on the highways is 65 mph. It could be 70, or 75, or 50 mph. So what would be the impact of lowering the speed limit to 60 mph? We have good data from other countries with lower speed limits. Each lowering of the speed limit by 5 mph is associated with an approximately 8% reduction in deaths on the freeways and interstates.

In the US, we have about 40,000 traffic deaths yearly, so that 8% reduction translates to between 1500 and 2000 traffic deaths a year. If you dropped the speed limit down to 50 mph, that would save 10,000 to 13,000 lives. If I drive from Portsmouth, NH, to Cleveland, Ohio, how long would it take at 60 and 65 mph? Driving at 65 mph, the trip would take a little over 10 hours; at 60 mph, it would take 11 hours. The difference is about 51 minutes for the whole trip. Is the 51-minute shorter trip worth 2000 lives? Before you say, “Of course,” it’s not that simple. We could lower the speed limit to 0, and then there would be no traffic deaths, but then you’d have to walk to Cleveland. Or you could get a horse, but they can buck or step on you. Pretend the US had a transportation czar, and by some mischance, you were tapped to take the position. It’s all on you. What are you going to do about speed limits?

Well, for sure you aren’t going to ban cars. That ship has sailed. So you are going to have to balance the needs of commerce, transportation, convenience, and safety. But, you might protest, can you put a price on a human life? Well, we don’t like to do that with individuals, but we do it every day for groups. My mentor, Bill Derby, Ph.D., was a captain in the Coast Guard during WWII before he became a psychologist. He told me about nights when he commanded ships looking for missing fishing boats in gigantic storms. He told me that after 2 days of battling the waves looking for the missing. After 2 days, they went home; a calculation was made that he and his crew were in peril, and that after 2 days, the likelihood that anyone in the fishing boat was still alive was close to nil. So there is a cost-benefit analysis that was made about the lives of the fishermen vs. the lives of the coasties.

Does the idea of making decisions that involve human lives make you queasy? Too late, you are the transportation czar. So, 50 mph, or 65? Glad it’s you and not me. But the point of all this is that there is no perfect answer. When it comes to these kinds of serious decisions, there are different needs and priorities, and no decision will be without consequences. There would undoubtedly be some downsides to legalization. But as with speed limits, it’s always a matter of competing harms and benefits.

So with that in mind, what reasons do politicians and the medical establishment give against recreational cannabis? Here are some common points they make:

- Cannabis lowers intelligence and impairs memory, attention, or executive skills in adults.

- Long-term, frequent use supposedly causes global neuropsychological decline.

- Modern, high-potency products are claimed to create permanent brain changes, even for adults.

- Cannabis acutely impairs judgment and decision-making, raising public safety risks (e.g., for driving and work).

- Legalization increases cannabis use disorder (addiction) and harms mental health.

- Brain scans show damage or abnormal structure in adult users.

- Societal costs: legalization is said to burden public health, healthcare, and workplace productivity.

Well, that’s pretty daunting. If these arguments are true, no responsible politician, physician, or citizen should support recreational marijuana. But are these claims true? Mostly not, but some explanation is probably required.

If, like so many hundreds of thousands of people across the globe, you’ve been following this blog (soon to be available in Mandarin and Urdu), you know I’ve discussed the difference between what scientists call statistical significance and clinical significance, but let’s recap. Statistical significance means that a study has found a difference or effect that isn’t likely to be due to random chance—basically, the math checks out. But clinical significance asks if that difference is actually big enough to matter or make a real impact in people’s lives. Let’s illustrate this with an example. You may recall some years back when all the news shows and papers claimed that moderate drinking of red wine, maybe a glass a day, was good for your heart. CNN ran a story in 2000 titled “Red wine may protect against heart disease.” Great, laissez les bons temps rouler! But not so fast. What was the actual clinical impact of a glass of red per day on your health? Nada, bubkis, zip. These studies reached statistical significance but had no clinical impact. But before you say this is just an example of how you can lie with statistics, let’s remember that 2 things can be true at the same time. Studies that reach statistical significance are important because they point the way to further research; remember ivermectin? Early studies showed a statistically significant antiviral effect, but the findings didn’t hold up and didn’t show any meaningful clinical utility.

Short digression here. Sometimes I see these kinds of stories in the media, and I don’t even have to look at the data and methodology to know that someone is blowing smoke. Let’s take an example. Sometime back, I saw one of these stories that trumpeted, “Adolescents who listen to rap music have more sex!” Sounds interesting, and at first blush, seems to make sense. After all, if your teen spends all his time listening to songs with titles like “Me So Horny” and “Just Don’t Bite It,” they are bound to get ideas. But how would you prove it? You could give the youngins self-report inventories asking what kind of music they like and how often they do the horizontal mambo, but everyone lies about sex. You’d probably have to do an experiment. You’d get two large darkened rooms and set up infrared cameras. Then you’d get 100 adolescents, herd them into the rooms and play either Mozart or a medley of the most explicit songs by Megan Thee Stallion and Lil Wayne and tally up the number of times the members of the two groups got busy. Of course, that could never happen.

You’ve probably picked up on a recurring theme in my postings: Scientific studies might show statistical significance, but that doesn’t mean the results are actually meaningful in the real world. Case in point—lots of headlines love to trumpet dire warnings about cannabis and cognition. But here’s how the trick works: researchers find a tiny difference, maybe in test scores, often in groups like chronic heavy users or teenagers. Then, like clockwork, those findings get blown up and served as a cautionary tale for every adult who ever took a puff. The reality? For most responsible, moderate adult users, the cognitive impact is somewhere between negligible and nonexistent.

It gets better. Sometimes animal studies or experiments with extreme cases get tossed into the mix as proof that disaster lurks for everyone, but those aren’t telling the story of most adults’ lives. Most users show no meaningful change in memory or thinking—no matter what the averages say. So, next time a headline tells you to panic, remember: group averages and worst-case scenarios are the smoke and mirrors of health journalism. The actual risks for regular folks are usually a fraction of what the policy debates and scare stories suggest.

Statistical significance is a big deal for scientists—it means a result isn’t just luck, and yes, it’s crucial groundwork for future research. But for people trying to live their lives, clinical significance is what really matters. If a difference doesn’t make a dent in your daily functioning, it’s a lot of math about nothing—just like all those old wine stories, or the ivermectin hype that fizzled when researchers asked, “But does it actually help?”

OK, are we all clear on statistical significance vs. clinical impact? If not, don’t feel bad; many of your physicians don’t either, but stay with me.

A short aside here about the diagnosis of addictions. It might be helpful to look at the actual DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for cannabis use disorder. I know not all of my readers are mental health professionals, so here’s a word of explanation about the DSM-5-TR. DSM-5-TR stands for “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision.” It is a revision of the fifth edition (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association, with “TR” indicating that it is a text revision rather than a new edition. I’m old enough to remember the DSM-III. It was about the size of a trade paperback and was 494 pages long. The DSM-5-TR was released in 2022 and includes updated diagnostic criteria, descriptive text, and new coding information for mental disorders. The paperback edition is 1056 pages, and it now weighs about 5 pounds. It is pretty much the Bible of psychodiagnosis, and more importantly for some, you need the diagnostic codes to submit a bill to insurance and get paid. Some of the newer diagnoses have been controversial. For example:

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Ongoing arguments focus on whether normal childhood behavior and attention variability are being pathologized, with critics citing possible educational and pharmaceutical industry influences.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): The broadening of autism’s criteria led to debate about overdiagnosis and the validity of combining previously distinct conditions, such as Asperger’s disorder, under one umbrella category. Also, as the diagnosis became less specific, more and more people are now autistic. You may have heard that there is an epidemic of autism (I’m lookin’ at you, Robert Kennedy Jr.) but it appears not to be true; we just lowered the bar, increasing the number of cases.

- PTSD: Back in 1980, to qualify for a diagnosis of PTSD, you had to be exposed to a major, life-threatening stressor that caused intense fear, helplessness, or horror, and it had to happen to you. By 1994, DSM-IV stated that it didn’t have to be something that you personally experienced; you could see it happen to someone else, but you still had to react with helplessness or horror. These days, DSM-5-TR further allows the diagnosis to be made if someone experienced actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, but you could qualify for the diagnosis by learning that one of these traumatic events happened to a close family member/friend (restricted to violent/accidental deaths) or by repeated/extreme indirect exposure to these events (such as first responders experience on a daily basis). It does specify that seeing or learning about such events by watching TV didn’t make the cut. Concerns have been raised that people experiencing understandable distress and normal grief are now being saddled with a psychiatric disorder.

Diagnoses related to substance use have changed as well. In DSM-IV-TR, they distinguished between substance abuse (problematic use of alcohol and drugs that caused problems in living) and substance dependence, which involved physical addiction. DSM-5 combined substance abuse and substance dependence into substance use disorder and added “craving” as one of the criteria.

There are some serious problems with a number of these diagnoses and the area of substance abuse is no exception; it’s not just my idea—these concerns have been raised by psychologists and psychiatrists who specialize in addictions. I’ll list the DSM-5-TR criteria for cannabis and I’ll note some of my personal concerns under the applicable criterion:

- Cannabis is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

Ok, you thought you’d smoke a joint, but what the hell, let’s fire up another? If you don’t miss work, neglect your kids, or drive into a tree, what’s the problem? I can see why this might be a warning sign of a developing problem, but that’s not what a diagnosis is meant to do.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control cannabis use.

This is one I can see. You’ve decided you don’t want to spend so much time slumped on the couch, playing God of War. You decide to cut down, but the next night, there you are again, stoned on the couch. Maybe you need some help. On the other hand, if that’s what you like to do, who am I to judge?

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from cannabis.

Again, this seems kind of judgey. Whose business is it of anyone else’s if that’s how you spend your time? Also, in a state with legal cannabis, you don’t have to hustle on the street to get some; you can just walk into the local dispensary and tell the amiable stoner you want 5 cartridges and a bag of watermelon gummies.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use cannabis.

Right, that’s why you went to the dispensary in the first place.

- Recurrent cannabis use results in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

Ok, this one makes sense. Functional impairment is where the rubber meets the road.

- Continued cannabis use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of cannabis

Also worth considering.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of cannabis use.

This one is iffy. If you are smoking so much you might lose your job; that’s a problem, but again, that could have gone under “recurrent failure.” But maybe you’ve decided that smoking marijuana is your new form of recreation, and you don’t feel like socializing so much. Is the American Psychiatric Association going on record as approving or disapproving of your hobbies? Why do a bunch of psychiatrists get to decide that birdwatching is good, but getting stoned is bad?

- Recurrent cannabis use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

Good call.

- Cannabis use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem caused or exacerbated by cannabis.

This one makes sense too. If you are getting more depressed or psychotic because of all the cannabis you ingest, seek help. If your asthma is kicking up because of your vaping, switch to gummies.

- Tolerance, as defined by either:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of cannabis to achieve intoxication or the desired effect

- Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount.

This is a real thing, but not really a problem until you hit high levels of consumption.

- Withdrawal, as manifested by either:

- The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for cannabis

- Cannabis (or a closely related substance) is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

This can happen at high levels of use.

Before we venture on, you might be wondering why the DSM-5-IV, the Bible of the American Psychiatric Association, does so poorly with some diagnoses. Allan Francis is a distinguished psychiatrist who has headed the task force that revises the various versions of the DSM and has tried to hold the line against what he sees as diagnosis creep and diagnosis inflation.

- There is no solid, agreed-on definition of what counts as “normal”—all attempts to define it end up circular or arbitrary.

- No general rule tells us what a mental disorder actually is or who has one—our criteria are vague and shifting.

- Most current psychiatric diagnoses are historical constructions, not clear-cut diseases.

- Any dividing line between normal and illness is fuzzy and can be moved easily.

- Small changes to diagnostic definitions can dramatically raise or lower the numbers of people labeled as mentally ill.

- Without a gold standard, the best approach balances the real-life risks and benefits of calling people “disordered” or “normal.”

- The DSM tries to set the boundary, but in practice, the labels stretch when there are incentives to diagnose.

- Financial and social incentives (money, services, insurance, drugs) reward wider and looser diagnosing.

- Drug companies drive expanding diagnoses through aggressive marketing to both doctors and the public, prioritizing profit over patient care.

- Diagnostic inflation carries real dangers: unnecessary medication, wasted resources, and the medicalization of normal distress or behaviors, which can expose people to stigma, side effects, and healthcare costs with little real benefit.

So with all that in mind, what reasons do politicians and the medical establishment offer against recreational cannabis? Here are some common points they make:

- Cannabis lowers intelligence and impairs memory, attention, or executive skills in adults.

- Long-term, frequent use supposedly causes global neuropsychological decline.

- Modern, high-potency products are claimed to create permanent brain changes, even for adults.

- Cannabis acutely impairs judgment and decision-making, raising public safety risks (e.g., for driving and work).

- Legalization increases cannabis use disorder (addiction) and harms mental health.

- Brain scans show damage or abnormal structure in adult users.

- Societal costs: legalization is said to burden public health, healthcare, and workplace productivity.

Let’s look at these claims one at a time:

1. Cannabis Causes Declines in Intelligence and Cognition

- Population studies of heavy, long-term users show small average differences in IQ or memory—but most adult users show no clinically meaningful decline.

- These small group differences are often presented as inevitable outcomes for all users, when in fact, they represent the extreme end of use (chronic, early-onset, or folks who already had another condition).

- Many studies show that observed deficits disappear after a period of abstinence, especially for folks who started smoking cannabis as adults and use it moderately.

2. Long-Term, Heavy Use Causes Global Neuropsychological Decline

- Reports of “global decline” tend to look at large groups of people who started smoking cannabis as teens, then generalize to adults, even though those who started as adults typically show little or no long-term impact.

- The true proportion of adults showing clinically meaningful decline is very small

3. High Potency Means Lasting Harm Even for Adults

- Concerns about high-potency cannabis are supported by preliminary data in young users or those with pre-existing psychiatric risk but are applied to all adults regardless of dose or pattern of use.

- Data drawn from adolescents is frequently used to suggest adult risks without any real data to back it up.

4. Acute Memory, Judgment, and Workplace Safety Harm

- Laboratory evidence demonstrates acute impairments (short-term memory, attention) near the time of intoxication, but population risk estimates are often based on laboratory performance tasks, not real-world impairment.

- Many studies don’t account for typical adult consumption patterns (occasional, moderate use) nor do they check to see if these folks have any real-world problems, such as backing into the paper shredder. at the office.

5. Cannabis Use Disorder and Addiction Rates

- Population increases in cannabis use disorder diagnoses post-legalization are presented as catastrophic, while most adults use cannabis non-problematically.

- Prevalence increases are small relative to the population of users, and diagnostic thresholds changed over time, making longitudinal comparisons difficult and often exaggerated.

But onward. Let’s remember that we live in a state where alcohol is not only widely available but is also one of the cornerstones of the New Hampshire economy. When I first came here for a job interview in 1986, I was astonished to see that there was a huge liquor store on Interstate 93, one on each side of the highway. A giant store full of booze right on the main north-south thoroughfare seemed like a bad idea to me, but selling cheap liquor to folks from Massachusetts was a huge source of revenue; it still is. I’m reliably informed that NH state stores sell upwards of $750,000,000 worth of liquor. This translates to about $150,000,000 in revenue for the state coffers, and that’s a lot of liquor. So we sell liquor enthusiastically but ban cannabis. Let’s compare the downsides of liquor to those of cannabis:

| Harm Area | Alcohol | Cannabis |

| Violent Crime | Involved in ~1 in 4 violent crimes in U.S.; strong causal link | No consistent link; not reliably associated with increased violence |

| Domestic Violence | Major risk factor; increases intimate partner violence rates | No significant association; legalization linked to reduced rates in some studies |

| Physical Health | Causes ~140,000 deaths/year in U.S. from liver, cancer, heart, and other diseases | Virtually zero fatal overdoses in adults; may raise heart attack (~25%) and stroke (~42%) risk in heavy daily users (but remember the base rate problem) no confirmed deaths |

| Motor Vehicle Death | ~25% of U.S. traffic fatalities (about 10,500/year) involve alcohol | Cannabis impairment increases risk (OR 1.5–2.5), but substantially fewer deaths than alcohol; most deaths from combined use |

| Psychiatric: Psychosis in Low-Risk Individuals | Alcohol may cause delirium/psychosis only with heavy use or withdrawal | New-onset psychotic episodes from cannabis in people without prior vulnerability is <0.1% per year (about 1 in 10,000 daily users); most cases are acute and resolve |

Clearly, the dangers of this heathen devil weed have been exaggerated in the service of some other agenda.

Then there is the issue of what is really going on day to day. I’m 15 minutes from a bunch of dispensaries right across the border in Maine. Maine is unusual in that they have a higher limit for how much cannabis you can buy per day. You can buy 2.5 ounces a day, or 10-0.5 gram cartridges a day. If you bought 10, and you limited yourself to a couple puffs in the evening, how long would that last? At least a year. And in Maine, those limits are per day; you can go back the next day and buy another 10. Vermont and Massachusetts have lower limits but still allow you to buy plenty. Fun fact: 90% of New Hampshire residents live within 20 minutes of legal cannabis. And I can’t help but notice that when you drive into New Hampshire from other states, there are no police checkpoints stopping people to search their cars. The upshot of this state of affairs is that anyone who wants cannabis in this state has as much wacky tobaccy as their hearts desire.

Again, there are real negative consequences to substance use, but you have to distinguish between serious, moderate, minor, or negligible harms.

So, as a result of politicians like Senator Gannon and Governor Ayotte’s refusal to allow the will of the people to prevail, are New Hampshire residents deprived of cannabis? Not even close. New Hampshire is a small state, 190 miles north to south and 90 miles east to west at the longest points. 50 percent of the population lives within 20 minutes of the Massachusetts border. Let’s cut to the chase: almost 80% of the NH population lives 20 minutes from all the weed they could ever want. And these states will sell you plenty if you want some at competitive prices. As far as I can see, all the New Hampshire Republican senators and the governor have accomplished is an arbitrary curtailment of the will of the people of the Live Free or Die state and the loss of substantial revenue we could really use. Maybe it’s time for our leaders to rethink their positions.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.