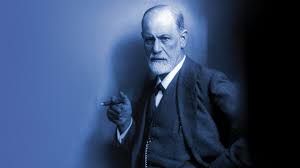

I’ve mentioned in other posts my ongoing interest in brewing and fermentation. It started early, mostly as a byproduct of my desire to get hammered, but then it became what I would call a compelling interest. This reminds me of a quote from Freud in “Civilization and Its Discontents.”

“Life, as we find it, is too hard for us; it brings us too many pains, disappointments and impossible tasks. In order to bear it we cannot dispense with palliative measures. There are perhaps three such measures: powerful deflections, which cause us to make light of our misery; substitute satisfactions, which diminish it; and intoxicating substances, which make us insensitive to it.”

My understanding is that the three palliatives Freud was alluding to were

- Powerful deflections—anything that grabs your interest and makes you forget everything else. These are clearly different for different people. Some people collect stamps, some fly-fish, and others tailgate at NFL games. Some people even publish blogs

- Substitute satisfactions—Freud was talking about art, religion, relationships, anything that makes you happy and gives meaning and lessens our suffering

- Intoxicating substances—kind of speaks for itself

Hmm. How did I get from brewing beer to Freud? Well, it could be argued that if you take up brewing as a hobby, you’ve checked boxes 1 and 3; if you are awed by the wonders of fermentation, you could even make a case for box 2. I hate to disagree with Freud, but while my life has had losses, pain, and some disappointments, on balance I’ve had a pretty good time, probably better than I deserved.

In any case, one of my compelling interests for a long time has been fermentation in general and making wine and beer specifically. In my 30s, I brewed beer often, in 5-gallon batches. After that, I backed off a bit, busy with my family and career. Also, that was when craft brewing really took off, and there was suddenly plenty of great beer just waiting to be sampled.

About 10 years ago I got back into it. I somehow stumbled on a book entitled “Make Mead Like a Viking” by Jereme Zimmerman.

It’s an interesting book that combines history, explorations of Viking culture, and a how-to guide to brewing mead. For the uninitiated, mead is fermented honey. It’s been around for a very long time, with some evidence that it was made as far back as Neolithic times. This is when humans began to shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture and herding. That makes sense. If you were limited to wandering around gathering berries, wild roots, and plants, and you didn’t have a horse to ride, it would be hard to schlep around brewing supplies. Also, it was around the same time that humans started making pottery, which allowed them to have vessels that would hold fermenting liquids.

Humans probably simply stumbled upon fermentation. For thousands of years, dinner (and probably breakfast and lunch) was a bowl of boiled grain (porridge). If you leave a bowl of porridge sitting around, at some point wild yeast will settle on it and start turning whatever sugars are present into alcohol and CO₂. Same thing with fruits and berries. I can’t help but imagine the first few times this happened. I think of our Neolithic hero getting up and scarfing down the bowl of boiled barley that had been sitting around for a couple days. It probably tasted funny, but these folks were in no position to be picky. Then I imagine this bloke chatting with a neighbor and telling them that they had a really great breakfast and that suddenly they had a very positive feeling about the future. The same thing will happen if you leave some ripe fruit around too long or throw a few pounds of berries into a pot. The magic happens because wild yeast is everywhere, particularly on the skins of fruit. Diluted honey will also do the trick.

Contrary to what you might have read, Vikings weren’t always swilling mead. Also, they didn’t wear horned helms. Why not? The idea was that if your enemy managed to get in a good cut at your coconut, there was a chance that the blow would glance off rather than splitting your skull. But horns would direct the sword or axe right into your headbone, and that would be bad. But back to mead. Honey is not that easy to come by, so it was used to make mead on special occasions. Sugars in general weren’t plentiful; you were pretty much limited to fruits and malted grains. One advantage of brewing and fermenting is that a barrel of beer or wine lasts longer than fruit or porridge, and you could make a big batch of it, plus you could party. Which reminds me of something I heard once from a stand-up comic. He was tired of hearing about the dangers of alcohol and observed that “If it wasn’t for alcohol, most of us wouldn’t be here.” I also recall that modern sage, Homer Simpson, saying, “Alcohol: the cause of and answer to all of life’s problems.”

Let’s circle back to “Make Mead Like a Viking.” Craft brewers and winemakers can be pretty sophisticated, and their recipes and procedures can get complicated. It makes sense; if you have something very specific in mind, you have to do what you have to do to get there. But it can get pretty intimidating. You have to hold malted barley (and you’ll probably need several types) at about 160 degrees to create the sugar, use a hydrometer to check the specific gravity, boil it for an hour while adding different strains of hops at specific times; like I said, complicated.

I’m glad that some people are dedicated and serious craftsmen, but I’ve never been that good at complicated sequential procedures like this recipe. In everything besides psychology, quick and dirty is more my style. That’s what I like about Jereme Zimmerman’s approach. He is a fan of letting nature take its course and sometimes being pleasantly surprised. For example, he recommends using wild yeasts from fruit peels or other sources. The downside of this is that it’s hard to exactly reproduce a recipe you liked, but he’s pretty flexible and doesn’t look down on people who buy a commercial beer or wine yeast. What I like about the book is the basic message that you should relax, let nature take its course and enjoy the results. It’s good advice. I’ve had batches of beer and wine that weren’t what I expected, but they’ve all been drinkable and I’ve never had a batch that I’d call bad. His basic mead recipe calls for honey. How much you use for your mead depends on what you are shooting for. 1 to 2 pounds per gallon gets you what is called “small” or “quick” mead, with about 5-10% alcohol. At 3 pounds per gallon, you can get up to 12-14% alcohol. Here’s the thing: yeast eats sugar and the byproducts are CO₂ and alcohol. But most yeasts die when the alcohol gets to about 14%. There is a lesson there somewhere but I can’t quite figure out what it is. Maybe something about global warming?

So if you want to make a batch of mead, you need honey and water to start. Different types of honey give different flavors, but I have to be honest, I’m not that discriminating. I generally go out and find the cheapest honey I can find. These days you can get grocery store honey for about $5.00 a pound. That comes to about 37 simoleons for a 3-gallon batch, or $2.50 a bottle. As I wrote this, I wondered, where did the term “simoleons” for dollars come from? I am reliably informed by Perplexity AI that the term became common in the 1800s. It was derived from the British slang for a sixpence, which they called a “Simon,” possibly after Thomas Simon, a famous engraver. This somehow became linked to the name for a French gold coin with the face of Napoleon, appropriately called a “Napoleon.” Get it? Simon+Napoleon=Simolian. But as ever, I digress.

You need a couple more ingredients. Yeast needs nutrients to keep it happy and vigorous. You can buy commercial yeast nutrients easily enough, but you can also just throw in a handful of raisins. You also need a source of acid, because unlike grapes or apples, honey doesn’t have any. Good wine has a bit of acid. You can just make a cup of strong black tea and add it to the mix, but that’s not your only option. If you are feeling all Euell Gibbons, you can use oak leaves or bark. Some lemon or orange juice will also do the trick.

So for a 3-gallon batch, you need water (preferably spring water), honey, and some combination of tea, oak leaves or bark, raisins, and maybe some citrus. You take the bottles of honey and sit them in a pot of hot (not boiling) water so you can pour it. You heat up about a gallon of water, then add the honey. Don’t boil the honey because it might scorch in the pot. Let it cool down a bit and add the tea or citrus, then take a whisk and whip it, whip it good; this adds a bit of oxygen, which I am informed makes the yeast happier still. At this point you can pour the honey water into a container (maybe a clean plastic bucket with a lid) and top it up to 3 gallons with more water. Once it’s warm, but not hot, you throw in a packet of yeast, cover it up, and let it go to work.

A word about yeast. You have lots of choices. Organic raisins have lots of wild yeast on them and will get your mead going. The downside is that wild yeast is unpredictable and each batch will vary, but that’s a matter of personal choice. You can always use bread yeast. It works perfectly well but can only handle about 10% alcohol and can give the mead a bready taste. But you can also buy packets of commercial brewing yeast and there is a bewildering variety. Expert mead makers often recommend Lalvin D-47, Red Star Cote des Blancs/Premier Blanc or Wyeast 4632, all available on Amazon or from brewing supply houses. But here’s what inspired this post. I’ve discovered a new yeast that has made me rethink brewing and meadmaking. It’s called Kveik, which I am reliably informed is the Norwegian name for “yeast.” It was apparently handed down from Norwegian farmhouse brewers who would use it, dry the sediment at the bottom of the vat, and use it again, generation after generation. At some point in the past, some random strain of wild yeast got together with more run-of-the-mill domesticated yeast and became super yeast. How super? Stay with me here. Let me count the ways.

Normal brewing yeast like to ferment at room temperature, about 64-72 degrees, while kveik works from 86 to 104 degrees. Those kinds of temperatures would kill your normal yeast. And it ferments at lightning speed. When I’ve brewed beer in the past, I’ve put the yeast in and gone to bed and when I woke up, the beer (called wort at this point) would just be starting to bubble, and it would take up to 2 weeks to finish up. I added the kveik yeast to my brew in the evening, and it was bubbling away in about an hour. When I woke up the next day, it was bubbling so hard that it blew the stopper out of the fermenting vessel. What once took 2 weeks could now be done in 3 days. And when you make beer, you generally start it in what’s called a primary fermenter. For most people, that’s a 6-gallon plastic bucket with a tight-fitting top with a hole for a fermentation lock. A fermentation lock is a handy plastic gadget that lets the CO₂ out and keeps air with bacteria and wild yeast from getting in. You let whatever you are fermenting work for a while, and as it gets to the limit of alcohol that the yeast can tolerate, it dies and settles to the bottom in a process called flocculation.

Then you use a J-shaped tube to siphon the stuff into a secondary fermenter, usually one of those 5-gallon water jugs you see in water coolers. This leaves all the dead yeast at the bottom and speeds up the process of the beer clearing up. This is called racking for some reason. But with Kveik, the Wonder Yeast, that’s not necessary because it settles rapidly to the bottom. The whole process can be over in 4 days as opposed to 2 weeks with normal brewing yeast. If you want it fizzy, siphon it into bottles and add a little more sugar to create carbonation. Wait a week for the stuff to get fizzy, and you are in business. One warning: if you want to carbonate, you have to have the right bottles. An average bottle of beer has about 20-30 pounds of pressure per square inch. If you pour your fizzy beverage into a wine bottle, the pressure will force out the cork, and your wine or beer will be dripping from the ceiling. If you put it in a mason jar and crank the lid down, it will explode like a bomb and create glass shrapnel. So what to do?

Traditionally, you saved up your empty beer bottles and bought a capper and used what are called crown caps to seal the bottles. But you can also buy plastic PET bottles with screw-on caps; these will set you back about 2 bucks a bottle. But there is a cheaper solution. You can go to the grocery store and buy 32-ounce bottles of club soda. Around these parts, you can get the grocery store brand for about 79 cents apiece. I recently went to buy some and then hesitated; what was I going to do with all that club soda? Then I had one of those moments when another part of your consciousness asserts itself. A little voice in my head said, “Schmuck, you were going to drop $2 on empty PET bottles. This costs 79 cents; you can just pour the club soda down the sink, plus you can reuse them.” And so I did.

So, let’s make a batch of one of my favorite meads. Assemble the following equipment for a 3-gallon batch:

A primary fermenter—I use a food-grade 5-gallon bucket with a lid, easily purchased at Lowe’s, Home Depot, or your grocery store. Or you can go to an online brewing supply store and get one with a gasket for a fermentation lock. If you want to go low-tech, you can skip the lid and cover the top with a sheet of Saran Wrap or other plastic and tie it on tightly; a large rubber band will work as well. The string or rubber band will allow the pressure to bleed off and keep nasty bacteria or wild yeast from getting in.

You might want a secondary fermentor. As I mentioned, this can be a plastic 5-gallon water jug, but if you follow this recipe, you won’t need one.

4 feet of plastic tubing, also not absolutely needed.

12 32-ounce club soda bottles

Then the ingredients

- 4 pounds of honey

- 6 cans of frozen apple juice concentrate

- 1 packet kveik yeast

- Yeast nutrient or a handful of organic raisins

- 1 cup of strong black tea, cooled

- 3 gallons of spring water

Note: If you want, you can scale this recipe down to one gallon. Just use 2 pounds of honey and 2 cans of concentrate.

Get a large pot and heat up one gallon of water. It doesn’t have to boil; just get it hot enough to dissolve the honey. The honey bottle should be sitting in another pot of hot water to warm it up so it flows easily. When the honey is warm, pour it into the pot with the hot water. Grab a spoon and a whisk and stir it so the honey dissolves, and use a little elbow grease to beat some air into it so the yeast has a source of oxygen. One trick I’ve used is to hit it with an immersion blender, which kills 2 birds with one stone. Add the semi-thawed apple concentrate and yeast nutrient, raisins, and tea. Put the lid on and let it cool till it is warm but not too hot, below about 100 degrees. Pour it into the primary fermentor, add about a quarter packet of kweik yeast and cover it with the lid or plastic. I’d put the whole thing in a warm place, like your boiler room. If you don’t have one, you can wrap it with a heating pad or just cover it with a blanket. You want it over 75 degrees and below 100 degrees.

If the temperature is in that range, it will only take 2-4 days to complete fermentation. How do you know? If you are using a fermentation lock, it will stop bubbling and start to clear. At this point, you might want to transfer it to a secondary fermenter. You can use a J-tube, but in a pinch you can just get a big funnel and pour it into the next container, leaving behind as much of the dead yeast on the bottom as possible. This is why it’s good to use a transparent water bottle, because you will be able to see how it’s settling and clearing. If it is taking a long time to clear, there are steps you can take. The easiest way is to get some unflavored gelatin. Add about half a teaspoon to half a cup of cold water, and let it sit there for about 15 minutes so it can absorb water. Then heat it to about 165 degrees; don’t boil it, or you risk making mead jello. If you have a cooking thermometer, you can heat it on low on the stovetop, or you can use your microwave in 10-second bursts until it is warm enough. Then just pour it into your mead and give it a gentle stir. In 24 to 48 hours, your brew should clear up. But there’s nothing wrong with it being a little cloudy. After all, people pay top dollar for hazy New England-style ales, and the yeast has B vitamins. Think about it; do you think Sven Bluetooth, the Viking warlord, fresh from slaughtering his enemies, worried about a little haze in his mead? I think not.

What you do next is up to you. If you don’t want it carbonated, just siphon it into bottles and let it age for as long as you can hold out. If you do, you can siphon it into those soda bottles you collected, and before you screw the cap down, add some sugar syrup. Take a cup of sugar and mix it with a cup of water. Stir till the sugar is dissolved and let it cool. You’ll need to measure carefully, since too much will cause your mead to foam out of the bottle like soda from a shaken can. I find the easiest way to do it is to get a syringe without a needle from your pharmacy and dose each liter bottle with 12 milliliters of syrup. It’s probably a good idea to make your first batch still, which is a fancy way to say no bubbles. If still mead was good enough for the likes of Ragnar Hairybreeks, it’s good enough for you.

Once you have the basic process down (and it ain’t rocket science), there is no end to the variations you can try. Back when mead was first popular, people had lots of very specific names for these variations:

- Cyser (what we just made) is honey and apple juice or cider

- Pyment is made with grape juice

- Methaglin is mead with herbs and spices. You can use cinnamon, cloves, coriander, or thyme and anything else that seems like it might work. My advice is that less is more

- Braggot is honey and malted grain, a kind of hybrid beer-mead

- Melomel is honey and any fruit or fruit juice you feel like using. You can get a quart or two of pomegranate, mango, or cherry and add it to the mix.

A word of caution. If you use more honey, and you can go up to about 3.2 pounds per gallon, the result may have up to 16% alcohol. Normal wine is about 12% alcohol. Mead that strong can knock you legless if you aren’t careful. If you decide to make your batch that strong, take it easy and use small glasses, or you won’t make it past the 1st quarter of whatever NFL game you are watching. Also, a mead hangover is a thing out of legend. You’ve been warned.

Addendum

There is a beginner’s recipe for mead that has been kicking around the internet since Jebus was in short pants called Old Joe’s Ancient Orange Mead. I’ve never made it, but it is popular and, by all accounts, pretty drinkable. Here it is (1 gallon batch) in all its simplicity:

Old Joe’s Ancient Orange Mead

Ingredients

- 3.5 lbs clover or your choice of honey (will finish sweet)

- 1 large orange, cut into eighths (rind and all)

- 1 small handful of raisins (about 25; more or less is fine)

- 1 stick of cinnamon

- 1 whole clove (2 if you prefer a stronger spice)

- Optional: a pinch of nutmeg or allspice (very small)

- 1 teaspoon of Fleischmann’s bread yeast (traditional, but you may substitute a mead or wine yeast)

Instructions

- Use a clean 1-gallon carboy or jug.

- Dissolve the honey in a little warm water, then pour into the carboy.

- Wash the orange well, slice into eighths, and add to the carboy (rind included).

- Add raisins, cinnamon stick, clove, and optional spice.

- Fill to about 3 inches below the neck with cool water (leave space for foaming).

- Shake vigorously with the cap on to aerate.

- Add yeast on top; swirl gently if desired.

- Install an airlock and leave it in a dark place at room temperature.

- After major foaming stops in a few days, top off with water as needed.

- Ignore it for 2–3 months until the oranges sink and the mead clears. Bottle and enjoy.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.