I don’t know if I’ve mentioned it, but I am a magician. Not a Gandalf-style wizard, although that would be cool. I mean the “now you see it, now you don’t” sleight-of-hand kind of magician. I’m reasonably good, not quite professional grade, but skilled enough to be entertaining. I can vanish and reproduce coins and sponge balls, do a few selected card tricks, the linking rings, that kind of thing. If I practiced for a couple months, I could probably do reasonably successful walk-around magic in a local bar and not humiliate myself.

My interest in magic and sleight of hand started early. My maternal grandfather, Zaddie Gaylin, died when I was quite young, maybe 7 years old. I only have a few memories of him. One that sticks out is him taking me to Jean’s Funny House on East 9th Street in Cleveland.

They sold all kinds of tricks and novelties there; you could stock up on whoopie cushions, fake vomit, and special pellets that turned your uncle’s cigar into one that exploded. Spoiler alert: Exploding cigars didn’t actually explode a la Bugs Bunny.

What they did was fizzle, pretty much as if you broke off a piece of a sparkler and inserted it into the tip of a cigar. Not nearly as dramatic and entertaining as a real Bugs Bunny-style cigar explosion, but it did minimize the facial scarring and ruptured eardrums that the real deal would have no doubt caused. I did use them on my father and several uncles to good effect; looking back, what a delightful urchin I must have been.

I also scored a bottle of disappearing ink. You squirted it on a tablecloth or garment, and it did indeed look like ink, then it faded away. I recall going over to see my father’s parents, Papa and Buby Ruth. Papa was not an imposing figure; he might have been 5’3” tops. He looked like an Eastern European immigrant from central casting. He wore slacks, a dress shirt buttoned all the way to his neck, and sometimes a suit coat, elbows shiny with wear. We were sitting at the table when I pulled out my little bottle of disappearing ink and just let him have it on his white shirt. I still recall, vividly, the look on his face; he was clearly thinking, “Ok, it’s come to this. My grandson has lost his mind.” Luckily for me, the ink faded away, and his consternation turned to amusement.

I had a close relationship with Papa. He had been a kind but stern parent to my father, and my dad told me that he never actually had a conversation with him. I had plenty; I was fascinated by his stories about the old country (Kavarskas, outside of Vilnius, Lithuania). I was full of questions: what did you eat, did you go to school, and what was it like there? Some of what he told me was pretty interesting. He told me that he had actually seen Cossacks, and he had nothing but contempt for them. I asked if they were as fearsome as I had been led to believe, and he told me, “Yeah, real tough guys, good at killing their own people.” He also told me he had been to Siberia, although I’m not sure why. I recall asking him how cold it was there. He explained that it was so cold that if you took a hot cup of tea outside and threw it into the air, it would burst into a cloud of ice crystals and fall to the ground as “snow.” I guess he was caught up in the memory, because to illustrate, he picked up a full tumbler of water and flung it into the air, dousing my father and me with the contents. We sat staring at each other with much the same expression Papa had when I doused him with disappearing ink before we started laughing.

When I got a little older, I realized that because of his heavy Yiddish accent, he really couldn’t hear the difference between the sounds of the letters V and W. I had just seen the Smothers Brothers on Ed Sullivan and borrowed part of their routine for an impromptu experiment. Here’s how the dialogue went:

“Papa, when you lived in Kavaras, did you ever drink wodka?”

“Vell, not all the time, but sometimes happing that I would drink shot or two wodka.”

“Did you ever drink so much that you would womit?”

“Vell, maybe once or twice I womit.”

“Tell me, Papa, did you ever womit in the Wolga?”

Papa considered this last question for a moment, then smiled. “Boychik, I think you are laughing on me.”

His name for me was “Chochum,” which in Yiddish literally means wise man or sage. In common usage and context, it can be a way of calling someone clever or smart but can also be used ironically, as in “wise guy.”

But back to magic. My grandfather bought me a little Egyptian-looking sarcophagus that held a small King Tut mummy. It’s easier to show you than explain its workings:

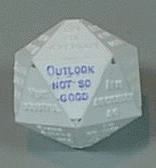

I can’t tell you how many hours I played with it. I knew it involved magnets but wasn’t quite sure how, but I didn’t break it to find out. My magic 8 ball was a different story. I spent a long time developing a theory of how it might work and decided there was a geometric figure inside that would float to the surface, pressing one of the sides to the little window. Finally, I had to know. I took my father’s ball peen hammer and my 8 ball out to the backyard and smashed it, and by God, I was right. It turns out that the geometric form inside is a regular icosahedron, with 20 sides:

But back to the narrative at hand. Zadie bought me a couple other magic tricks. There was the ball and vase:

The coin slide:

These are called self-working magic tricks because they rely on some mechanism or fixed mathematical principle and don’t require any sleight of hand or manipulation.

They are great for kids but have some drawbacks if you want to take your magic game to the next level. One problem is that they only do one thing. You get your coin slide and amaze your friends by turning a penny into a quarter. Inevitably, they ask you to do it again. After 2 or 3 repetitions, all the magic is gone and it’s getting tedious. Also, all good magic tricks need a big finish, and the King Tut trick has none.

For some reason, lots of young people, mostly boys, get interested in magic at about 12–13 years old. That’s what happened to me. I got a couple of books on magic and tried some of the simple sleights and vanishes they suggested. I’d give them a shot, with poor results, and then decide they were too hard and give it up. Here’s the thing: you really have to practice. I promise that if you try, you could learn to palm a coin convincingly. But it would require a couple hundred repetitions. That sounds like a lot of practicing, but it could be done in about 15 minutes a day for a week. My problem was that I just didn’t have the patience. Lots of kids have the same problem, and I think it is the rule rather than the exception. I had it worse than most. Lots of things came easily to me, but when they didn’t, my reaction was, “Who needs to know that anyway?” The idea that I should do something methodically, over and over again until I had it right, was foreign to me. That explains why I can’t play a note on the piano after several years of lessons. The idea of actually practicing something that you can’t do well until you can hadn’t been part of my outlook or training.

But as you grow up, your frontal lobes settle in, and you start thinking about things more rationally and systematically. Also, sometimes something someone says or something you read clicks a switch and you gain insight; this almost never comes from where you might expect it. In my case, I decided I would learn to juggle. I went out and bought “Juggling for the Complete Klutz.”

It had 3 square beanbags, which are good because you don’t have to chase them or get them out from under the couch with a mop handle. I highly recommend the book; after a week of practicing, I could actually juggle. One of the authors wrote something that stayed with me; I don’t have the book anymore, so this isn’t a quote, but he pointed out that to learn to juggle, you have to drop the beanbags many times. The mistake most people make is that they get tense and frustrated when the dropping happens. But this is a mistake; since you have to drop the beanbags many times, each drop brings you closer to your goal. Reading this, I had one of those “Huh, never thought of it that way” moments. And it applied to many of life’s challenges and endeavors, magic being one of them.

A little background on magic. It comes in many flavors. One type of magic is stage magic. You may have seen David Copperfield, Lance Burton, or David Blaine on TV, sawing people in half, making doves appear out of nowhere, and making elephants disappear. These days you have to go to Las Vegas to see that kind of thing. Should you wish to become a stage magician, I’d strongly urge you not to try the infamous bullet-catching trick. The basic idea of this trick is that the magician has a marksman come on stage along with a volunteer. The volunteer marks the bullet so it will be identifiable later. Then the magician walks downstage, and some kind of target is set up between the marksman and the magician, usually a pane of glass or a plate that will shatter to show that the bullet was actually fired. The gun is fired, the plate shatters, and the magician staggers theatrically. He then opens their mouth to show that they have caught the bullet in their teeth.

The problem with this trick is that several magicians have died performing it. One was killed when a piece of a ramrod broke off in the barrel of the rifle being used and was fired at the magician, killing him. The most infamous example of this kind of fatality occurred with a famous magician who called himself Chung Ling Soo.

Chung Ling Soo deserves some discussion. His real name was William Ellsworth Robinson, born in Westchester County, New York, in 1861. He tried a number of names and personas as a performer, but when he heard there was an agent looking for a Chinese magician for a stage act, he made himself up to look Chinese, including what we would call “yellowface” make-up. Around this same time, there was an actual Chinese magician named (wait for it) Ching Ling Foo who was very popular.

Robinson adopted the similar-sounding name and copied Foo’s name. He claimed to be the son of a Scottish missionary and a Chinese woman who was orphaned and brought up by a Chinese magician. He wouldn’t speak during his act and used an interpreter when talking to the press; he didn’t speak Chinese but made Chinese-sounding gibberish noises that were then “interpreted.” [Note: For a more in-depth discussion of Chung Ling Soo, check out “Chung Ling Soo: The Magician Who Led a Double Life and Got Shot on Stage” at: https://www.amusingplanet.com/2022/09/chung-ling-soo-magician-who-led-double.html]

Robinson actually went so far as to have his stage assistant disguise herself as Chinese; she called herself “Suee Seen.” Robinson did a version of the bullet-catching trick that involved a gimmicked gun with an extra barrel. Something malfunctioned during the performance, and he was shot and died from his wounds. This brings to mind a scene from the movie “Body Heat” from 1981. The protagonist, played by William Hurt, wants to kill his girlfriend’s husband and make it look like he died in a fire at his factory. Hurt plays a lawyer, and he seeks out the advice of one of his clients, an actual arsonist played by Micky Rourke. Rourke tells Hurt that his best advice is that he not try his hand at arson:

“Hey now, I want to ask you something. Are you listening to me, asshole? Because I like you. I got a serious question for you: What the fuck are you doing? This is not shit for you to be messin’ with. Are you ready to hear something? I want you to see if this sounds familiar: any time you try a decent crime, you got fifty ways you’re gonna fuck up. If you think of twenty-five of them, then you’re a genius – and you ain’t no genius. You remember who told me that?”

Good advice for many endeavors. I liked the lines so well that I included them (cleaned up a bit for a general audience) in one of my books, “Getting Started in Forensic Psychology Practice,” available at fine bookstores everywhere.

There are other styles of magical performance. One of my favorites is close-up magic. This is the kind of performance done for one or several people, at a table or bar. Since the magician is so near to the audience, they usually use cards, coins, sponge balls, or common objects like napkins or saltshakers. Personally, I’ve never found card tricks very interesting, nor can I do them well. They require a good deal of sequencing and certain kinds of rote memory, which have never been my best thing; I’ve been known to get tense just sorting socks. When I’ve tried to do tricks like the cups and balls, I’ve always found the deceptive moves easy enough; it’s remembering which moves to do next that’s difficult. Here is the professor himself, Dai Vernon, doing his classic cups and balls trick:

This trick has been around for a very long time.

I should mention that magicians take a very dim view of people who explain how a trick is done. If you’re teaching your padawan the trick, you can do it, but it’s customary to keep it secret. That being said, basically every standard magic trick in the world is now explained in books you can buy on Amazon or watch on YouTube, so if you must know how to bake a cake in a hat, you can find out easily enough. Luckily, most people just want to be entertained, so this isn’t as big a problem as it might be.

An offshoot of close-up magic is impromptu magic. These are the kinds of little tricks you do for your nieces and nephews at family gatherings. I’m guessing that almost everybody had an uncle or family friend that used to pull a quarter out of their ear. There are other, better impromptu tricks than that, and you can use common objects to do them, such as spoons and forks, saltshakers, napkins, pencils, and rubber bands. I always carry some half dollars, rubber bands, and maybe a couple sponge balls around with me so I can perform, should the need arise.

So, I hear you ask, how does magic work? Like most things, it’s complicated. There are the actual moves (sleights), and they range in difficulty from pretty easy to ridiculously hard. The basis for most close-up tricks is palming. This is the technique of concealing something in your hand so that the spectators don’t know it’s there. The easiest thing to palm is a sponge ball, which is exactly what it sounds like: a 1 ½- or 2-inch ball made of sponge rubber. It’s easy because you can squish it into a cranny in your hand and then produce it full-sized. You can do the same with coins or other objects, but they lack the squishability. You hold the sponge ball in your right hand and pretend to put it in your left, but instead you palm it in your right. Hey, presto!

But here is where it gets interesting. Think about it; I just put a sponge ball in my left hand, but now it’s not there. Wherever could it be? If you gave it a second’s thought, it would be obvious. Clearly, I’m not Merlin or Dumbledore; I’m just some bald guy with a big head. It’s obviously still in my right hand. So how does this trick work?

That’s where the real magic comes in. Magicians have developed an astonishing, intuitive grasp of human perception and thought processes. Neuroscientists have made this explicit, but magicians understood the way this works for many centuries. For example, they know how you think, and after years of practicing sleight of hand, so do I. I know you will look where I look, so I look at my left hand and purposely forget about the ball in my right hand. If I clenched my right hand, that would draw your attention, so I keep it loose. I also don’t clench my left hand; I keep it puffed out as if it were holding something, like a sponge ball. These moves—my looking where I want you to look, holding my hand like there was something in it, and looking at the moving hand—all of that is called misdirection. Misdirection involves focusing your attention on something irrelevant or disguising something I don’t want you to see. It’s easier than you might think, and you see it outside of magic all the time.

You can see misdirection all game long if you watch the NFL. A play-action pass is a great example of this; the quarterback makes it look like he’s handing off the ball to one of the running backs, then drops back and passes downfield. The best example I’ve ever seen of misdirection on the football field is this clip of the Seattle Seahawks punting to the Rams in 2014. The Seahawks’ punter kicks the ball left, while all but one Rams defender runs right, as if that’s where the ball is going. Apparently the NFL won’t let you embed one of their YouTube videos in a blog, but if you go to YouTube and look for Rams Amazing Trick Punt Play Fools Seahawks (Week 7, 2014), you can view it there. I had to watch the clip three times before I realized what happened.

Petty criminals also use misdirection. Pickpockets generally work in groups; one creates a disturbance that attracts the victim’s attention while another bumps into you and relieves you of your wallet. It’s not that difficult to manipulate someone’s attention. Check out the selective attention test below:

Another way magicians manipulate perception is related to what has been called “change blindness.”

Other tricks rely on our brain’s ability to fill in missing information seamlessly, and it happens to you more often than you think. Here is an example. Wherever you are sitting, look over to the right, then quickly look to your left. Here’s the deal: while your eyes were moving, you were functionally blind. This function is called saccadic suppression; the visual system “edits out” the blurred images created when the eye moves and allows you to have a stable image when your eye reaches the new target. The effect only lasts a few milliseconds, but you don’t notice it. How can that be? You don’t notice because the brain uses pre- and post-eye movement data to create the illusion of an uninterrupted view. Your brain expects the world to remain stable, so it fills in the blanks. We also use context cues to fill in missing information. Here’s an example; it’s called the Cambridge University Paragraph:

“Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.”

You didn’t have any trouble reading that, for a couple of reasons. The first is pattern recognition. “Cmabrigde” isn’t correct, but it is a close enough match to “Cambridge” that you have no trouble recognizing what it probably says, particularly because the first andlast letters are right. The second is our ability to use context clues. “Cmabrigde” might be confusing, but it’s right there next to ” Uinervtisy” and that provides more information about what the words say. Finally, there is the gestalt principle. Here are some examples:

See the triangle? There is no triangle; there are just 3 Pac-Man-looking shapes suggesting a triangle and your brain filled in the rest.

Here’s another:

It takes a moment, but the seemingly random dots quickly transform into the image of a Dalmatian.

I could go on about the relationship between magic and psychology and probably will at some point. But I think learning magic was helpful to me in my work as a psychologist. It is one thing to read or be told about attention, memory, and concentration. It is another to actually manipulate these functions in another person. Sometimes it was hard for me to believe that my audience couldn’t see what I was doing, and that’s a potential problem for beginning magicians. If you worry that the audience will see what you are doing, there is a good chance they will. In addition to learning the sleights and routines of a trick and knowing how to manipulate their memory and attention, there is an additional factor if you want the trick to work, a “secret sauce,” if you will. The famous magician Tony Slydini probably put it best when he said, “If you believe it, they’ll believe it.” Good advice for many endeavors.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.