So, it was 1978, and I had managed to get accepted to Yeshiva University’s doctoral program in school psychology. Good news, right? But as my father once told me, you try and try to make the team, and then you have to come off the bench and play the game. At that point in my life, I was arrogant enough to believe that it would just work out. But it wasn’t that easy. I flew to NYC and stayed for a week with my cousin, Sheldon Gaylin, a noted psychiatrist, and his family. I commuted into the city every day and tried to locate an affordable place to live. I ended up in a basement on Carmine Street in the Village, but that wasn’t a long-term solution. Looking back, what was I thinking? A privileged Jewish kid from the burbs, and I was going to sashay into Manhattan and take the town by storm? Looking back, the arrogance and chutzpah are still astonishing. I recall looking for apartments, and it was a real eye-opening experience. There were affordable apartments in the Bowery, but after seeing a couple, I was nearly in tears. I decided that if that was my only option, I’d crawl back to Cleveland and rethink my life.

I kept looking. One place wanted to rent me an actual closet that was just big enough to lie down in. In retrospect, it was one of the better options. Then there was the guy who offered me a platform about 6×4 above his refrigerator screened off with bamboo shades. Things were grim. I’m not sure how, but I finally snagged a position as a live-in counselor in a residence for intellectually impaired adults in Gramercy Park. My job was to get the residents up, get them breakfast, send them off to their programs, and take some of them to their medical appointments. In return, I received a room one floor up, my meals, and about $85 a week pocket money. I know it sounds like chump change, but that was about $400 in 2025 dollars, and I actually saved money.

This wasn’t my first time working in a position like this. The year before, I had worked as a psychiatric technician on a locked psychiatric ward at University Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio. You know those old movies where someone gets committed to a psychiatric hospital and they are flanked by several burly guys in whites? That was me, but not that burly. But it was very different at the Residence. For one thing, this place was open, and nobody was held there against their will. They were free to come and go and had a great deal of autonomy.

I really enjoyed living there. I think that getting that up close and personal with the people who lived there gave me insights I could not have possibly obtained otherwise. An example? Well, when you do psychological assessments, you only have limited contact. Even though you obtain a great deal of information, you are just getting the short version. With the folks at the residence, you sit around and chat, watch TV, have lunch in restaurants, and do all of that. Let’s remember that I was a naive kid from an affluent suburb and knew almost nothing. After a while, I developed concern for these folks and real friendships. The whole patient/staff thing breaks down, and you realize that they are people just like you are. An added benefit was that some of them were a riot to work with.

And I better clear something up right now. Most of the folks living at the residence were what we would now call intellectually impaired; some were also autistic. There are some people out there who might find my anecdotes offensive and assume I am making fun of them. I am not, and I know my gentle readers would never make such assumptions. They were my friends, and I have kept in touch with a number of them for many years. Has a friend of yours ever done anything that made you howl with laughter? Same thing here. Do I sound defensive? Well, we live in strange times, and I’ve gotten the “hit dog howls” crap a few times now in other forums. This is directed at drop-in trolls rather than my readers. All I can say is that if what I write offends you, stop reading now. Maybe you can use the time you save to signal your virtue someplace else. Better yet, you could take some of the time you use parsing everything you read on social media for uncool attitudes and privilege and maybe actually help someone who needs it. Ok, now we all know where we stand.

There was Michael, who I now realize was autistic. He could be difficult at times and a bit dramatic. One time, he wanted me to take him to the bank. I had to make a few calls and told him I’d take him, but he’d have to wait a while. He came back every 5 minutes to see if I was ready. Around the 5th time, he glared at me when I put down the phone. “How long, Eric? How long must this torture go on?” But he could be amiable as well. His parents had been NYC socialists, and it had rubbed off. Now and again he would break out his guitar and start belting out socialist songs like “I’m Sticking to the Union.”

Then there was my buddy Ronnie, a Black man with a bald head. He understood what was said to him but had very limited expressive language. If you asked him a question about what he was going to do that weekend, he would say something like “Doo doo doo, dada, my momma.” But here’s the thing. If you didn’t know better, you would think he was just speaking a different language. The tone, flow, and emphasis were just as though he were speaking normally.

I know a lot more about these kinds of problems now than I did at the time. Ronnie had a kind of language problem called aphasia. The word “aphasia” has Greek roots. “Phasis” means “speech” or utterance, while the prefix “a” means “without.” But there are different types of aphasia, depending on which portion of the brain has been damaged. For example, one type is Wernicke’s aphasia. These folks have a type of brain damage that allows them to speak fluently, but they talk nonsense. Here is an example of their speech, courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic:

Well, the cheese is running on the ladder, smoodle pinkered, and I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before. Yes, exactly. It’s just, you know, the goster is splining, absolutely sunflower.”

These unfortunate folks can no longer understand the meaning of language. The part of the brain that controls the actual production of speech works fine, but they don’t really understand what is being said to them. On top of that, for some reason they don’t realize that they don’t know what has been said, and they don’t know that they are not making sense.

That wasn’t what was going on with Ronnie. If you asked him to pass you the salt, he’d do it. I believe he had what is called Broca’s aphasia. It is like the flip side of Wernicke’s. Broca’s patients struggle to say what’s on their mind. Their speech is generally labored and telegraphic. Here is an example of someone with Broca’s who has been asked how they came to be in the hospital, courtesy of AI:

“Yes… ah… Monday… er… Dad and Peter… hospital… and ah… Wednesday… nine o’clock… ah doctors… two… er… teeth… yah.”

Usually, their speech lacks prosody, which is the tone, pace, and rhythm of language. Want an example? The words “You’re coming” can be either a statement or a question depending on whether you say it with a rising or dropping inflection. If you are an MCU fan, consider “I am Groot.” But in recent years, those who study these kinds of things have discovered that some people who have Broca’s aphasia have preserved prosody and can even use it as a tool to communicate.

I’m going somewhere with this. I’m going somewhere with this. Ronnie received social security benefits for his disability. I don’t remember just how it happened, but some paperwork required by the government didn’t get to where it was supposed to go and he was summoned to the local office, which just happened to be in the World Trade Center. I thought it might be an opportunity for some of the other residents, so we hopped the subway and went to the towers. We were ushered into the office, and the gentleman in charge offered Ronnie and me chairs. He was polite but firm and demanded to know why Ronnie has not returned his call or responded in writing to his queries.

Mustering all my self-control to keep a straight face, I turned to Ronnie and told him to explain in his own words why he had been so neglectful.

You are probably way ahead of me at this point. Ronie earnestly tried to explain, complete with hand gestures and appropriate expressions of regret, but what he said was, “Do da, dododa, my friend, my mama.” To his credit, the social security guy attempted to keep his composure; I did too, but it wasn’t easy. He managed to pull himself together and said, “I believe I understand the situation. I’ll complete the paperwork.” We shook hands and left. I took the gang up to the observation deck, then we had dirty water hot dogs and went home.

But before all this, there was moving day. I moved from Carmine Street by borrowing a two-wheeler and hauling my paltry possessions to the residence, about a mile away. Once I got settled, I came downstairs to meet the folks. I looked up, and a bony, gawky man with an odd gait was hustling over to me. He stopped with his face about 3 inches from mine. In a strange, nasal sing-song voice he asked, “What is your name?” I told him, and he said to himself, “Yes, that’s right.” Then he asked, “What’s your birthday?” I told him it was 11/4/1955. Without hesitating, Joel said, “It was a Friday!” I had no way of checking at the time, but I was able to lay hands on a perpetual calendar, and damned if he wasn’t right. Later, armed with the calendar, I asked Joel what day my birthday was on in different years, and he was never wrong.

He had other talents. He had memorized the streets of the boroughs of NYC, and L delighted in asking, “Is East 167th Street one-way or two-way?” I had no idea, but when I checked, he was always right. L. would also routinely kick my ass in Scrabble, but you had to watch him, because now and again, he’d cheat. I’d look at his triple word score and ask, “L, is zippldorph a word?” Joel would cackle and reply, “It’s not a word!”

Joel had also memorized the top one hundred songs listed in Billboard magazine pretty much as far back as they had been listed. If you asked him what had been the top song on November 11, 1978, he’d just tell you. As it happens, it was (God help me, I wish I were making this up) MacArthur Park sung by Richard Harris. I recall when my son was about 6, I played it for him and sang along. He howled with laughter at the stupid lyrics, to wit:

Spring was never waiting for us girl

It ran one step ahead

As we followed in the dance

Between the parted pages and were pressed

In love’s hot heated iron

Like a stripped pair of pants

OK, that’s bad enough; love is something you slap on the old ironing board and iron like a pair of pants, stripped no less? Note that it’s stripe-ed, not striped. But it gets worse with the chorus:

Macarthur’s Park is melting in the dark

All that sweet green icing flowing down

Someone left the cake out in the rain

I don’t think that I can take it

‘Cause it took so long to bake it

And I’ll never have that recipe again

A rain-sodden cake as a metaphor for ruined love? We can only be grateful that the writer, Jimmy Webb, hadn’t been inspired by an overcooked meatloaf with congealed gravy. I don’t think that I could take it.

And then there’s the interminable musical interlude that starts about four minutes and 40 seconds into the song and continues for another 2 minutes. But the pièce de résistance comes at 6:45, where Richard Harris bellows out “Oh noooooo!” like a freshly castrated water buffalo.

But L. For all his amazing abilities, Joel had his challenges as well. He would sometimes melt down if his routine was disrupted, and if he was really peeved, he’d angrily tell you, “Meow, meow, you shall have no fish!” At one point, the residence washing machine broke down, and for a few days, the folks had to use the laundromat. The residence was on East 20th St. between Park and 3rd Ave., just across from Gramercy Park. We had arranged for the folks to go to a laundromat on 3rd Ave. The residence took up the 3rd and 4th floors of an old church rectory and we had an elevator. I was coming out of the kitchen when I noticed a trail of laundry detergent leading from Joel’s room to the elevator. Puzzled, I rode the elevator down to the ground floor and found that the trail of detergent continued across the lobby and down the 3 steps leading to the street. Now I was really curious. I followed the trail east on 20th for a block to 3rd Ave., then took a left and walked another half block to the laundromat. Inside, I found L in a considerable state of agitation. He had gathered up his clothes and grabbed a large, partially opened box of detergent and stuck it under his arm, open side down; hence the trail. When he arrived at the laundromat, he realized that the detergent was all gone and he was rapidly striding around the place, muttering to himself and alarming the other patrons. Luckily, I had shown up just in the nick, and was able to calm him down and buy more detergent.

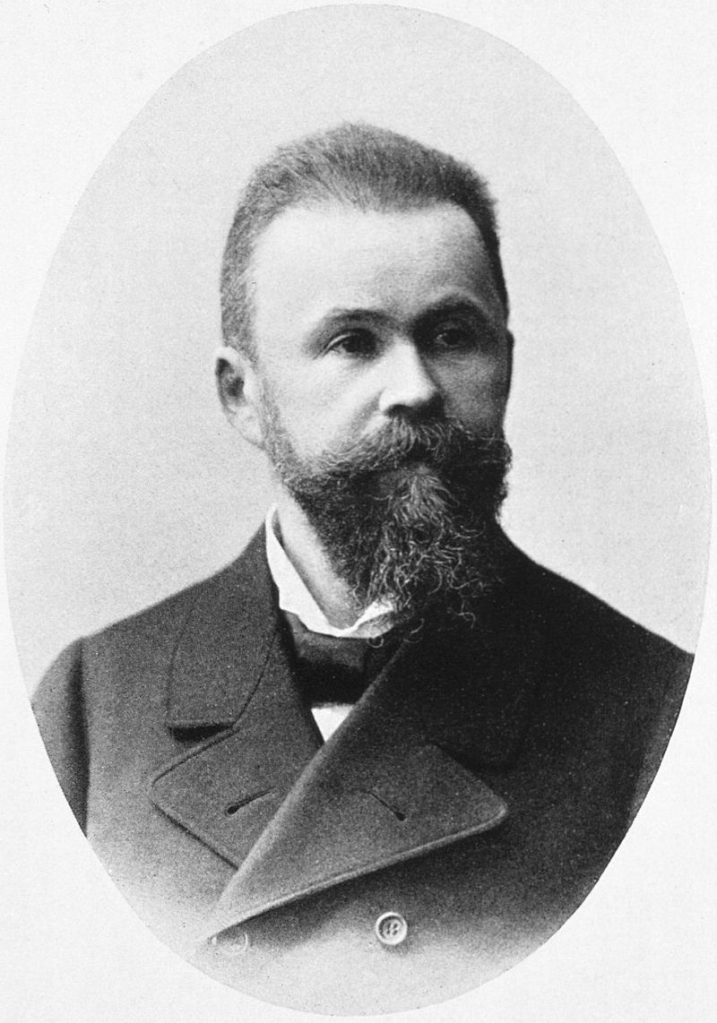

If you’ve been following this blog, you have probably realized that I am an inquisitive bloke. Staff members had access to the resident’s files and I pored through L’s. To my surprise, I saw that he had been a patient of Kurt Goldstein’s. By a remarkable coincidence, I had just listened to a lecture on his work in my neuropsychology class at Yeshiva U.

Goldstein was born in Germany, where he studied neuropathology and specialized in different manifestations of brain damage. He became interested in the work of Carl Wernicke (remember Wernicke’s aphasia from earlier in the post?) and became a physician when he was 25.

In 1933, he got on the wrong side of the Nazis and was held in a basement for a week; they let him out on the condition that he leave Germany and never come back. He took the hint and left for the US, where he joined the staff of Montefiore Hospital, which was affiliated with Yeshiva University, where I was studying at the time. I asked Joel if he remembered Goldstein and he said that he did and that he was “a nice doctor.” But wait, there’s more. In 1945, he collaborated with Sheerer and Rothman on a monograph entitled “A Case of an Idiot Savant.” Who was the focus of the monograph? None other than my buddy L.

Here is some of what Goldstein et al. had to say about L.

In 1937 an 11 year old boy, L. was presented by his mother to the writers

for neuropsychiatric and psychological consultation. The complaints about L. summed up to this: he could never follow the regular school curriculum, like a normal child, or learn by instruction. His general information was alarmingly substandard; he had made progress in only a few school subjects, and even in these, his achievements were very limited. His motivational and behavioral peculiarities had been an early concern of his parents. He had never shown interest in his social surroundings or in normal childhood activities. On the other hand, he had always excelled in certain performances.

However, he shows one unique interest in his human surrounding—an amazing phenomenon exhibited in the first minutes of the examination. Spontaneously the boy asks each of us, “When is your birthday?” Given the date, he answers in a fraction of a minute, “Dr. G.’s birthday was on Saturday last year, and Dr. S.’s birthday was on Wednesday.” A glance at the calendar proves him correct. We call others to the scene, and with amazing swiftness, L. gives correctly the day of the week of every person’s birthday. Moreover, he can tell at once exactly which day of the week a person’s birthday was last year or 5 years ago and on what day it will fall in 1945, etc. More closely examined, L. provescapable of telling the day of the week for any given date between about 1880 and 1950. Conversely, he can also give the date for any given week-day in any year of that period, e.g. the date of the first Saturday in May 1950, or of the last Monday in January 1934, etc. As much as we could determine, he makes no mistakes in his calendar answers. Though L. unquestionably takes delight in the recognition of his feat, he never seems aware of its extraordinary character in the same sense as a normal person (e.g. the reader of this, if he could master such a task).

That was my friend Joel, right? But he also had talents I never suspected:

L.’s rigid trend towards developing skills and knowledge only on his own limited terms of play-like function and sheer manipulative interest reappears in his musical ability. He shows a surprising musical capacity and sensitivity together with equally surprising gaps. He has absolute pitch, likes to play the piano for hours without being taught. Although he has learned to read simple scores, he plays only by ear, e.g. such melodies as the “Moonlight Sonata” or “Three Blind Mice,” and later, at 14, more difficult compositions, e.g. the “Largo” from Dvorak. Mostly, however, he will play monotonous sequences of his own fancy. He will rarely reproduce a tune he knows and then only on insistent demand. He loves the opera “Othello” to the degree of obsession, and can sing the “Credo,” “Si del” and the “Adagio Pathetique” from beginning to end. He sings the accompaniment or the Italian words as they sound to him. Without knowing the language he reproduces it purely phonetically. His interest in music includes a preference for the operas of Verdi, for Beethoven, Schubert and Tschaikowsky, all of whom he likes to hear on records.

Here’s a visual aid of L’s strengths and deficits:

| Remarkable Abilities | Severe Deficits |

| Instantly identified the day of the week for any date (1880–1950); named birthdays/weekday rapidly | Profound impairment in abstract reasoning and understanding causation, analogies, metaphors |

| Extraordinary memory for dates, names, and birthdays (social recall) | Unable to learn by instruction or study; unresponsive to teaching in all but rote or self-selected tasks |

| Exceptionally rapid, accurate manipulation of numbers; increased digit span with age | Extremely limited social awareness; aloofness except toward the mother; no genuine curiosity. |

| Unusual spelling skill (forwards, backwards, orally, in writing, either hand); retained new spellings | Speech repetitive, echolalic, and lacking meaningful dialogue; trouble answering questions appropriately |

| Absolute pitch; played piano by ear (refused lessons); recognized/completed melodies, opera arias | Fine and visuo-motor deficits: difficulty with utensils, impaired planning, poor part-whole integration |

| Retained/composed melodies, texts, compositions after hearing; reproduced phonetically/synesthetically | Emotional responses shallow or misplaced: fleeting tantrums/fears; rigid food/behavioral preferences |

| Strong associative and serial memory: counted rapidly by unusual intervals, learned rhymes/music fast | Unable to generalize: rote learning only transferred to identical contexts; couldn’t adapt knowledge |

| Misunderstood social constructs (age, time, relationships; e.g., “older” by order of birthdays) | |

| IQ consistently low (< 50); general facts/information subnormal despite cognitive “islands” |

But L was more than a list of strengths and deficits. I remember taking a group of the residents out to go roller skating in the West Village. When we got there, it was full up, so we had time to kill. I took the gang, including Joel, to a Greek restaurant on Bleeker Street. We had a bunch of what would now be called small plates: hummus, tzatziki, olives, souvlaki, and a half bottle of wine for everyone to taste. We were having fun, but L was getting restless. He’d jump up from his seat and rush over to the jukebox, no doubt memorizing the songs. But apparently, he’d had enough. I stood up at the table and began to sing at the top of his voice “When is Eric going to take me home! When is Eric going to take me home, home, home?” The other patrons were becoming alarmed, so I paid the bill and we beat feet for the residence.

A word about the “idiot savant” thing. People have tried repeatedly to come up with non-pejorative, respectful terms for people with lower cognitive abilities. In the mid-18th century, physicians developed a classification system for people with limited intellectual abilities. An idiot referred to someone with a severe disability (unable to care for self). An imbecile had a moderate disability (some self‑care and speech) and a moron had a mild disability (able to work but limited judgment). In the early 20th century, these terms were linked to IQ scores:

Idiot—IQ less than 25

Imbecile—IQ 25 to 50

Moron—IQ 51-70

These terms were not originally pejorative or insulting, but there is something called the euphemism treadmill. The idea is that a stigmatized group becomes associated with a negative label. Then well-meaning people decide to come up with kinder, gentler terms. It happens all the time. Want some examples?

Crippled → Handicapped → Disabled/Differently Abled

Soldier’s Heart → War Trauma → Shell Shock → Combat Fatigue → Battle Fatigue → PTSD

Garbage men → Sanitation workers → Environmental services → Waste‑management professionals

Why doesn’t it work? Because stigma attaches not to the word itself but to the underlying concept. Changing the label doesn’t remove prejudice—it only postpones it. I find these attempts to change minds by changing words admirable and well-meaning, but I think it reflects a basic misunderstanding of the nature of prejudice and bigotry.

But there has been some evolution about the idea of savant skills. The original idea was based on observations that some people like L had amazing abilities but very serious deficits in other areas. The “idiot” modifier has been dropped in favor of “savant skills.” Why? While most people with these amazing abilities are on the autism spectrum, some are not. There is a group that develops these abilities after brain injury, stroke, or the development of neurodegenerative disease. But there is also a smaller group of normal individuals who suddenly develop incredible skill for no apparent reason. These skills include:

Perfect musical pitch, and the ability to play complex music by ear after one exposure

The ability to draw scenes seen briefly with photographic accuracy

The sudden ability to quickly learn new languages

Flawless recall of nearly everything they have heard or seen.

How does this happen? Beats the hell out of me, but if my savant abilities are in there somewhere, I wish they would hurry and make themselves known.

Goldstein thought that L and people like him had a profound impairment in abstract reasoning. What’s abstract reasoning? It’s a slippery concept. It’s the ability to understand and manipulate complex concepts that are not linked to concrete objects or experiences. It’s easier to provide examples than explain. Looking at a handful of small change and counting it up is concrete. Understanding a common proverb requires abstract reasoning. That’s why for decades, psychiatrists and psychologists have asked patients to explain common proverbs during intakes, since overly concrete thinking is one of the hallmarks of several conditions such as schizophrenia, brain damage, and autism. If abstract reasoning is impaired, patients respond with concrete interpretations. Here are some examples of concrete and abstract interpretations:

| Proverb | Concrete Response | Abstract Response |

| “No use crying over spilled milk.” | “The milk is spilled; you can’t put it back in the pitcher.” | “The time to worry is before the damage is done, not after.” |

| “Rome wasn’t built in a day.” | “A city takes a long time to build.” | “You have to be patient and allow things time to happen.” |

| “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” | “You really don’t know if a book is going to be good until you read it.” | “First impressions can be deceiving.” |

| “Actions speak louder than words.” | “If you say you’ll help, you should do it.” | “What people do is more important than what they say.” |

| “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” | “Not all eggs become chicks.” | “Don’t anticipate benefits that might not come.” |

Back when I was working at a state hospital in Cincinnati, we’d do intakes with new patients. One question we sometimes asked was “What brought you to the hospital?” And as often as not, the answer would be “a cab” or “an ambulance.” It turns out that the strengths and weaknesses of folks with autism are much more complex and nuanced than Goldstein outlined in his monograph. But he did identify an important component of the condition. My clear impression was that L, blocked from understanding abstractions and social nuances, channeled his intellect into memorization and rote learning. I’ve often thought about what it was like to be him, but I really can’t wrap my head around it.

I left the residence after about a year. I moved to Brooklyn and found a couple of roommates, one of whom became my wife and the love of my life (spoiler alert, it wasn’t Stuart Waugh, although he was a good friend; just not what I was looking for in a spouse). I dropped by the residence whenever I had a chance, and over the years I continued to drop by. One time, I had stopped by and then headed up 5th Ave to catch my train home. I ran into L by chance. He was headed home from his workshop. Always gaunt, now he was skeletal. I’d been told he had been diagnosed with leukemia, but I was shocked to see him like that. He recognized me, but it was clear that his incredible memory was not working as it had in the past. We exchanged a few words and shook hands and said goodbye for what turned out to be the last time. I’m not given to sentimentality, but I wept all the way to Penn Station.

So that was L, a famous case and my personal friend. He was a celebrated case, but he was a real person like anyone else with strengths and weaknesses. The difference was that his strengths and weaknesses were much more profound on either end. I’m glad he found his way to the residence; I think he had the best life he could have had. More than glad to have made his acquaintance.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.