I was overdue for my dermatology appointment, so I set one up and went on in. By way of background, before I went bald and most of my hair turned white, I was a real redhead. You know the type. Green eyes, really pale skin, the kind that turns lobster red after a minute or two in the sun. And I certainly had a number of those blistering burns. I am so pale that people sometimes remark on it. I once saw a new rheumatologist; he looked me over and asked, “Are you always this pale, or have you been unwell?” So it was just a matter of time before I had sun-related skin problems.

Back when I was a kid, there was plenty of medical folklore that we all just believed until somebody finally pointed out that it wasn’t true. One of the most obvious examples I can think of is the idea that you couldn’t swim for 15 minutes after eating, and if you did, you’d get cramps and drown. This has since been revealed to be completely untrue, which shouldn’t be too surprising since I don’t know of anyone who entered the pool in an untimely manner after consuming a hot dog and a bag of chips and jumping into a pool. I became aware of this type of thing early on. When I was 16, they tried to stop us from smoking pot with fake facts. One of the things the health teachers told us was that if guys smoked marijuana, their testosterone levels would drop and they would grow breasts. I did a little research and discovered that they had arrived at this conclusion by extrapolating from one study done on rats. Apparently, they gave the male rats heroic doses of THC and discovered that their testosterone levels were lowered slightly.

From this small bit of data, these geniuses extrapolated to the idea that male high school stoners would be shopping for bras in no time. I think I mentioned in an earlier blog post that I had read a book about understanding statistics, which noted that to really understand a phenomenon, you had to have both a bird’s-eye view and a worm’s-eye view. The bird’s-eye view is derived from research and studies on large groups of individuals, while the worm’s-eye view is what you see going on around you. Giving the matter a little thought, I realized something. I knew a lot of guys who smoked marijuana, and none of them had suddenly grown breasts.

Getting back to the redheaded thing, the conventional wisdom of the day was that you just had to go out and expose yourself to the sun many times, and you would eventually acquire the ability to tan. In actuality, nothing could be more false. What was really happening was that you were frying the crap out of your skin and laying the groundwork for later basal cell carcinoma and worse.

So I went to the dermatologist, and she found a suspicious-looking lesion on my forehead and biopsied it. Unfortunately for me, it came back as basal cell carcinoma. This is one of those good news/bad news situations. Having any kind of carcinoma is bad news, but if you had to pick one, basal cell would be the way to go. My reading on the subject informs me that the treatment for this condition is about 99.9% effective, and if you take care of it in a timely manner, you can go about your business until something else kills you. They scheduled me for something called Mohs surgery. I had just assumed that Mohs was an acronym for something, but it turns out that it’s named after Dr. Fredic E. Mohs, an American physician. He started developing a procedure for removing the cancerous lesion from the skin, along with a thin layer of healthy skin around it to make sure no cancer cells were left behind.

So Wednesday, I got up bright and early and headed for the dermatologist’s office. They put me in a chair, tilted me back, and numbed up my forehead. The procedure itself is nothing; there’s a tiny pinprick when they numb you up, and then you feel nothing. After the first excision, they slap a bandage on your head and send you out to the waiting room while they check to see if they got it all. I was lucky and didn’t need another round. Then they stitch you up. The doctor said there might be a small scar that would fade over time. I told her to try and minimize any scarring, because I am just getting by on my looks. The nurse gave me a sheet with some instructions about how to take care of the wound and told me that after the anesthetic wore off, I might have some mild discomfort that could be managed with Tylenol. That was encouraging. I’ve always felt that if Tylenol takes care of your pain, you probably weren’t experiencing enough pain to justify the Tylenol.

I took the rest of the day off; nobody wants to see a psychologist with a bloody pressure bandage front and center on their coconut. I felt fine until I didn’t. Ever have a wisdom tooth out? You head home, all numbed up, and you think, “This isn’t so bad.” Then the novocaine wears off, and you feel like someone has applied a set of red-hot pincers to the place where your tooth used to reside. That’s kind of what this was like. First the area where they had removed about a dime-sized patch of skin started to hurt. Then the pain spread. I had a headache behind my eyes and soreness on parts of my head that the doctor hadn’t touched. I felt shaky and tired, and a couple ibuprofen helped but not enough.

I had a rough night, but I had the perspicacity to hang on to some Percocet from an earlier procedure. What’s that? Drug disposal day? You want me to drop off my unused painkillers for safe disposal? Your mama. Maureen Mart didn’t raise any foolish children. One of these days (like today) I’m going to need that stuff.

Thursday wasn’t a whole lot better. Constant headache, pain at the site, and I felt shaky and weak. I took it pretty easy, and some ibuprofen helped. Today I’m a bit better, but the headache is still there and gets worse when the ibuprofen wears off. So I had to ask, what gives? I thought I’d try to find out.

Just to provide some context, if you have been following my blog, you know that I am a forensic psychologist with a subspecialty in forensic neuropsychology. What I might not have mentioned is that in the last 10 years or so, my practice has changed, and I do a lot of what are called IMEs (independent medical examinations). Just to be clear, they are not medical, at least when I do them. I do file reviews in worker’s compensation cases and personal injury actions, and sometimes I evaluate these folks face-to-face. Usually, these cases involve mild traumatic brain injury (concussion) or posttraumatic stress disorder. If I’m doing a file review, my job is to see whether what’s in the file supports the diagnosis; I’m not diagnosing the person because I haven’t met or examined them. In some cases, I do face-to-face evaluations as well, but file reviews are more frequent.

Sitting and reviewing medical files all day, I’ve had to get up to speed on medical terminology. I sit at my desk, with Black’s Medical Dictionary at my elbow, and all of mankind’s accumulated knowledge at my fingertips. I see references to obscure medical conditions and look them up. You can’t do that for a decade and not learn a few things. Can Hashimoto’s syndrome cause symptoms of mania? Yes, it can. Can low potassium mimic acute anxiety? Apparently so. You can’t keep looking up all this information without learning something. It doesn’t make me a physician, but then, the things that physicians know are generally understandable by regular mortals.

So I have some ability to research questions, such as, “Do some people have problems after Mohs surgery?” There is AI, databases, Google Scholar, and all that. It turns out that the idea that most people have only mild discomfort after Mohs is both true and not true at the same time. How could that be? This is going to require a little science to explain, but I promise to be gentle.

Let’s start with medical standards for pain control. I’m sure that at some point you have been asked, “How bad is your pain on a scale of 0-10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain you could imagine?” This is called the Numeric Pain Scale. Dr. Henry Beecher, who deserves a blog post of his own. He was an anesthesiologist and medical ethicist who served as a doctor with the US Army in Italy and North Africa. After the war, he became chief of anesthesia at Mass General. In 1966, he wrote an article entitled “Ethics and Clinical Research,” which exposed unethical practices by physicians. These weren’t minor ethical lapses; they included withholding penicillin for rheumatic fever, infecting children with hepatitis, and injecting live cancer cells into patients without telling them. At the time, the members of the medical establishment initially howled like stuck pigs and played the “a few bad apples” card but eventually came around and started requiring detailed, written informed consent from patients and the creation of Institutional Review Boards at hospitals.

Beecher was also a controversial figure. After his death, his papers revealed that he had worked with the CIA on mind control and interrogations of prisoners; this may have involved the use of LSD. It’s a good bet that the subjects were not volunteers. It was also revealed that he consulted with Nazi researchers on the best ways to interrogate. There is a saying that no one is as bad as the worst thing they did or as good as the best thing, and I think that’s true. But most of us don’t live a life as full of contradictions as Dr. Beecher.

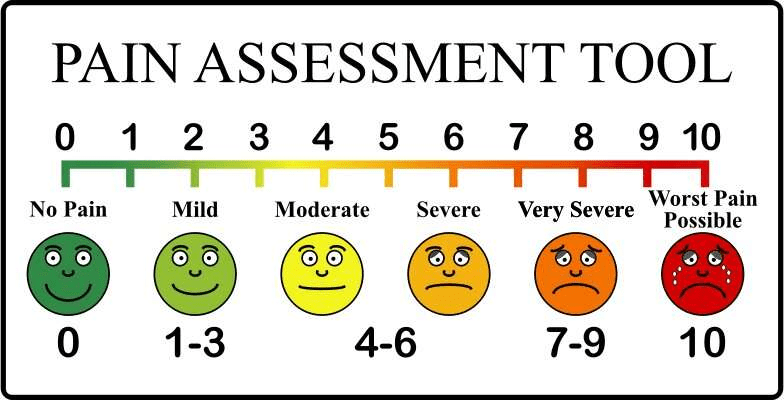

But back to the numeric pain scale. The way it is applied varies a little from one setting to the next, but generally pain is rated like this:

0=No pain at all

1-3=Mild pain

4-6=Moderate pain

7-10=Severe pain

Here’s a handy visual aid:

The scale isn’t perfect but has been widely endorsed by major health and physician organizations, including the CDC, the World Health Organization, and the American Academy of Pain Physicians. These organizations also indicate that patients should be kept at or below 4, pain-wise. It’s not perfect. I’ve used it a few times in my practice, and some people have trouble applying it. I recall one patient who had serious chronic back pain. They said their usual and current pain levels were both 10. Remember, 10 is the worst pain you could possibly imagine and I had explained that carefully. I pointed out the window at a guy who was ambling down the street. I asked, “If I went out there, doused that guy with gasoline and set him on fire, what do you think his pain level would be?” The patient quickly replied, “10.” Then I asked if their pain level was that bad. After a moment’s thought, they revised their level down to 7-8.

So, back to my case. I’m pretty good at chronic pain. At different points in my life, I’ve suffered from gout and migraines. You learn to cope; you can take to your bed, but in my experience, the best thing is to keep on keepin’ on to the best of your ability. The worst pain I ever experienced was when I had a herniated disk in my neck. I recall that it was winter, and I went outside to view Halley’s comet. When I raised my head to look up, it felt like someone had stabbed me in the neck with one of those broadhead hunting arrows. It took my breath away and went on for several months. I remember asking my physiatrist how people coped with such pain long-term, and he told me that they often became addicted to alcohol or drugs or killed themselves. In my case, it eventually resolved.

After my procedure, I was told that I would probably experience mild discomfort after and I was instructed to take Tylenol; I could alternate Tylenol and ibuprofen if it was a little worse than that. But it was a lot worse; I’d rate it as about a 6 on the numeric pain scale, and it went on through Friday, which was yesterday. I’m a little better now, but still at 3-4. I began to wonder what was going on and did some more research.

It turns out that two things can be true at the same time. My research revealed that it is true that the average Mohs patient has only mild post-procedure pain. But averages can be misleading, and this comes up in my work and court testimony. Let me give some examples of how this can be.

- Ten students take a test: 5 score 95, and 5 score 55. The mean (average) score is 75, but no student actually scored close to that—it’s just a midpoint between high and low performers, hiding the real pattern of achievement

- Imagine a company with 100 employees: 99 earn $30,000 per year, and the CEO earns $2,970,000. The average salary is $60,000, but almost everyone earns half that amount, and only one individual earns vastly more. The mean salary paints a false picture of the typical earnings

- In a neighborhood where three children are ten years old and one retiree is 90, the mean age (30 years old) doesn’t reflect the reality that almost everyone is a child or a senior

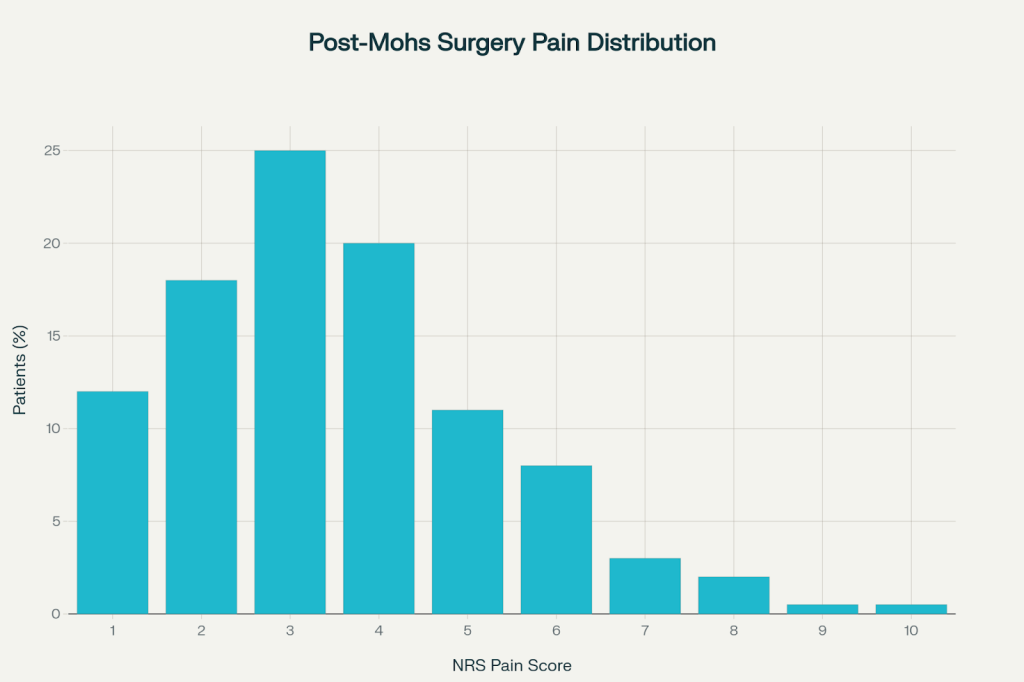

It turns out that people like me who have the procedure on the scalp or face have more discomfort than those who have it on other areas of the body. Here is a graph that shows the distribution of pain scores for those folks:

So, the average post-Mohs pain score really is around 3. But look carefully at the graph. A substantial portion of the patients had scores ranging from 4 to 10. How many? If we were looking at 100 patients, 39 would have moderate pain scores, 5 would be in the severe range, and 44% is darn close to 50%. So it was almost even money that I was going to have moderate to severe pain later that day. So, given these facts, was the procedure really done with my informed consent?

Before I answer, let’s talk about what informed consent is and where the idea came from. Physicians have been aware for centuries that they should let patients know what they were going to do to them, how much it would hurt, and what the outcome was likely to be. But the idea wasn’t clearly formulated until after WWII, when the Nazi doctors experimented on patients without their consent. This was later codified in the Nuremberg Accord in 1947. The first principle of the Nuremberg Code explicitly requires “the voluntary consent of the human subject” and goes on to lay out, in detail, what this involved:

- The patient has to be capable of giving consent. Some people with very low intelligence, those with dementia and others with similar conditions can’t understand what they are being told, and have to have an interested party stand in for them

- The patient can’t be forced or coerced

- They have to be informed about:

- What was going to be done to them

- How it was going to be done

- The risks and possible inconvenience expected as a result

The idea was that a procedure done without full informed consent was a form of assault, or more specifically, battery. We all hear about assault and battery, but they are not the same things. Assault is the threat that puts the victim in fear, as in “I’m going to kick your ass,” and battery is the actual ass-kicking; you can assault someone without laying a finger on them. In medicine, performing a procedure without informed consent is sometimes called medical battery because the person has not given knowing permission for what is being done to them.

Before I go any further, I want to be clear that I do not feel I was battered or assaulted during my procedure. I am grateful to the doctor who was doing their best to keep my lesion from growing and disfiguring me and eventually possibly killing me. And I don’t believe for a minute that anyone in that clinic intentionally misled me about what was in store. If I had been in enough pain, I could have called, and I have no doubt they would have called in some stronger medication. But why did it happen? I think a little background on the idea of informed consent is necessary.

The concept of modern informed consent in medical research and treatment is strongly rooted in the Nuremberg Trials, specifically the “Doctors’ Trial” of 1947. The Nuremberg Code emerged from these trials and specifically outlined voluntary consent as its first principle: “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.” This set of ten ethical standards was established in direct response to Nazi human experimentation during WWII, making clear that no person should be enrolled in research or subjected to medical procedures without full, voluntary, and informed consent.

While the basic idea of patient autonomy and consent in medicine predates the Nuremberg Code—there were earlier legal cases establishing the right to consent—the Code is widely considered the foundation of formal consent standards in research ethics, with its principles influencing international guidelines and laws, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The modern concept of informed consent in medical research and clinical practice is widely recognized as having been deeply shaped by the Nuremberg Trials and the subsequent Nuremberg Code of 1947. The first principle of the Nuremberg Code explicitly requires “the voluntary consent of the human subject” and sets forth detailed requirements for disclosure and decision-making autonomy in human experimentation. While some earlier instances of consent in medicine existed, the Nuremberg Code is considered the first major international document that established the standard of informed consent as essential. Its ethical legacy continues to shape consent requirements and protections for patients and research subjects worldwide.

So, it is clearly established that physicians and surgeons need to communicate levels of risk and adverse outcomes to their patients.

The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics lays out the requirements for informed consent, which include:

- The diagnosis (when known)

- The burdens, risks and expected benefits of all options, including foregoing treatment

- The nature and purpose of the recommended interventions

- Documentation of the informed consent conversation and the patient’s decision

That seems pretty clear, so why does it sometimes not happen effectively? There seem to be a few different reasons. One of these is that physicians are under a great deal of time pressure, particularly since medicine has been largely corporatized. This leads them, whether consciously or unconsciously, to simplify the information they give to patients.

Another factor is that surgeons tend to focus on average outcomes based on the output of risk calculators they use. Let’s say that a 62-year-old man who never smoked is experiencing moderately severe angina. He has high blood pressure but it is controlled with medication. His BMI shows him to be overweight but not quite obese. He has mild kidney disease and his blood sugar is elevated but he is not diabetic. The surgeon will punch these numbers into a risk calculator and come up with the following:

- Risk of major adverse events, including death, another heart attack or urgent bypass, within 30 days: 1-3%

- Risk of stroke or kidney injury during or shortly after surgery: 1-6%

- Bleeding or vascular complications—1-3%

I was curious and checked into whether these various risks were independent or cumulative. They are cumulative, which raises the overall risk of adverse outcome, but knowing this, physicians can take extra care and reduce risk. So I wondered, what if we were looking at the odds of an adverse outcome as though I were betting on a football game? We’d have two teams, “Team No Complication” vs “Team Major Adverse Event.” What are the betting odds? Here you go.

| Outcome | Likelihood (% chance) | Analogy to Football Spread |

| No Major Complication | 94-98 | Favorite: -14 to -20 |

| Major Adverse Event | 2-6 | Underdog: +14-+20 |

If we were betting on this like an NFL game, the favorite being favored by 14 to 20 points would be a huge spread and is unusual in professional football, where most games have -7 to -9.5 spreads. This week, the Green Bay Packers are favored by 14.5 points over the Bengals, making the Packers huge favorites. If you were just betting on who would win, you would bet very heavily on the Packers. [Update: The Packers won 27 to 18, and the 9 point difference didn’t cover the spread. That’s why its called betting.]

Moving back to the medical risk calculators, it makes a certain amount of sense that a busy surgeon would simply translate the risk for our patient into a percentile or a descriptive range. In this case, the patient would likely be told that his risk was moderate but not prohibitive, which is reassuring.

Other factors that interfere with clear communication of risk are related to physicians’ cognitive and psychological factors. They may be overconfident and feel like their performance is better than the risk calculation. And again, these doctors are under a lot of pressure. Mr. Patient needs to have the procedure; his overall odds are pretty good, so let’s wheel this guy into the operating room and get cracking because there are five more patients waiting behind him. Lastly, there are some concepts that are just really hard to break down for laypersons, as I know from my experience testifying in court; try explaining Bayesian probability to a jury sometime.

In the end, I did give informed consent—but like most things in medicine, the process can always be improved. True informed consent happens when patients feel genuinely informed about the full range of outcomes, not just the averages, and have the chance to ask the questions that matter most to them. It’s a reminder that medicine is as much about communication, empathy, and shared understanding as it is about diagnosis and treatment.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sheesh! I especially like the last paragraph. ….”they have the chance to ask the questions that matter most to them…”

LikeLike

I found this article quite helpful. Looking forward to more content like this.

LikeLike