A Gorilla Walks into a Bar

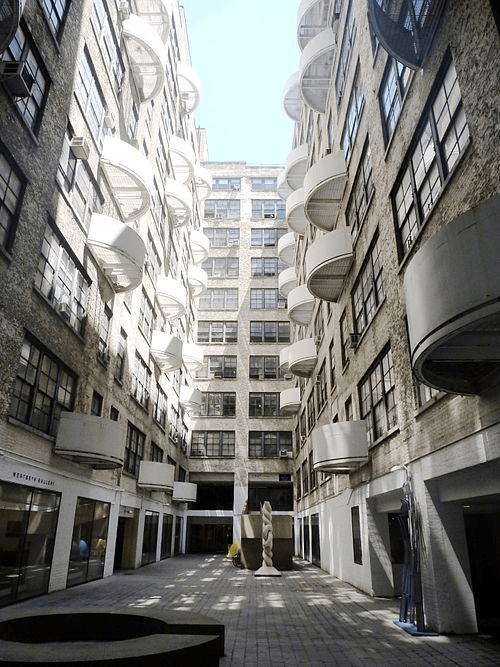

Back around 1982, Kay and I had gotten together as a couple and were living in a studio in Westbeth, the furthest extreme of the West Village.

I was still in grad school and needed a side gig to bring in some money. I had worked as a cook and bartender in my parents’ restaurant in Cleveland. I even had a certificate from the American Bartending School. I had taken their intensive 7-day course.

Generally, bartenders learn on the job, but there was a reason I attended. My parents’ first restaurant had a small bar, and we had no idea how to set up a bar. The world is full of things we experience every day, but we never consider how they work. Internal computation engines? Electricity? Computers? They might as well be magic; maybe they are. I recall discussing this with my father. He was musing about how the people who came to our restaurant really had no idea how their food appeared on their table. By way of example, he mentioned that they had a half-duck special at the restaurant and ran out. When the waiters would tell this to the diners, often as not they would say, “Can’t you cook up another batch?” They seemed to think that when they ordered duck, the kitchen staff took a raw duck out of the fridge, warmed up the oven, and roasted it to order, never mind that it would take an hour. In reality, you cook off a batch of ducks, stick them in the cooler, and then heat them up when ordered.

Same thing with pasta. The patrons seemed to think that when they ordered a bowl of pata boulengase. They thought that when the order came into the kitchen, the cook would put a pot of water on the stove and stand around till it boiled, drop the pasta, wait 12 minutes, and then pour it into a colander. Nothing could be further from the truth. We’d come in the morning and boil up 25 pounds of pasta, then cool it in cold water. Then we’d drain it, ladle up appropriate portions, and put them in a clean bus pan and thence into the cooler. We cooks would have a big pot of boiling water on the stove, with a handled colander inside. If you ordered spaghetti, we’d grab one of the pre-measured portions, drop it into the colander, let it heat up, then drain it and throw it on a plate. There would be various sauces on in the steam table, and we’d fill a ladle, pour it over the sauce, yell “order up,” and then it would go to the customers’ table.

And the same is true with setting up a bar. What kind of glassware do you need? Beer glasses, shot glasses, martini glasses, old-fashioned glasses—you never know what people will order. Then, what kind of liquor do you stock? It depends on how fashionable your bar is. But you will need several kinds of gin, just as an example. Most bars are set up with a rack of bottles below the bar called the well. If you just order scotch on the rocks or a bourbon, if you don’t specify a brand, that’s what you get. Maybe Gordon’s gin or Evan Williams. But maybe the customer is a bit more particular and orders a Bombay martini or a Jack Daniels on the rocks; you keep that on the shelf behind the bar. They call those “call brands.” By the way, it’s probably not a good idea to order a Patron margarita if you aren’t sitting at the bar, because it’s even money you’ll be getting Jose Cuervo from the well, and you won’t know the difference.

As usual, I’m going somewhere with this. And I’ll thank you not to be so impatient. After all, you are reading a blog entitled (in part) “Musings on the Passing Scene,” so what did you expect? I feel like Dustin Hoffman in “Lonesome Cowboy.” “I’m musing here! I’m musing here!”

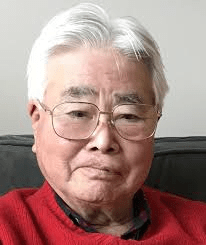

A few years back, I made the acquaintance of Shintaro (Sam) Asano, and we became friends. He was a famous engineer/inventor from MIT, and you are familiar with his work. How? Ever use a Xerox machine? Sam invented it, among other things. I looked him up on Perplexity AI and got this:

Shintaro “Sam” Asano was a Japanese-born American inventor, engineer, and entrepreneur best known for inventing the portable fax machine and making substantial contributions to electronics technology. Born in Tokyo in 1935, Asano survived the bombing of his home during World War II, then immigrated to the United States as a Fulbright Scholar in 1959 to pursue graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While working as a NASA engineer, his need to communicate complex technical instructions to colleagues, despite language barriers, led him to invent the fax technology that revolutionized business communication worldwide.

Sam knew I was fascinated by Japan and was the impetus for my trip. I was explaining how someone in Japan had proved mathematically that some professional sumo matches were fixed using the binomial theorem (I may cover this in another post; good story). He hadn’t heard about this and said, “So how come you know more than I do about Japan, and you’ve never managed to get there?”

We would talk about Japanese culture, and one day he told me something that surprised me, and that was that jokes, as we know them, aren’t really a thing in Japan. He told me that instead of stand-up comedy, comedy clubs went at it from a different angle. You and your friends would be at your table, and the comedian would sit down and tell you an amusing story. They also have Manzi, which features a slapstick comedy duo involving much slapping of the head with a rolled-up newspaper. But “Take my wife, please!” just isn’t part of their culture.

This was eye-opening. Like the patrons at my family’s restaurant who didn’t know how their meal arrived at their table, I’d had no idea that humor could be different from culture to culture. Oh, I knew that British humor came from a little different direction than humor in the US, but that was, to me, just a matter of style. This raised other questions like “What is humor?” and “Why do we laugh?” I did some research in my copious free time and came up with some answers and more questions. So, gentle reader, here’s what I came up with.

What is a joke?

A classic American/British joke has this structure:

1. The setup. This is where the characters and premise are laid out. It is factual and creates a narrative flow that the listeners expect to continue. To wit: A priest, a minister, and a rabbi walk into a bar.

2. The punchline. This involves a sudden twist that breaks the expectation created by the setup, as in “The bartender looks up and calls out, ‘What is this, a joke?’” Our expectations are broken, and the surprise triggers laughter for some reason.

A good joke is brief and does not have a lengthy setup. Timing is important, and the punchline should be delivered right after the setup. Also, US jokes often use the rule of three: two characters react similarly to the situation, and the third has a different and hopefully funny take, as in:

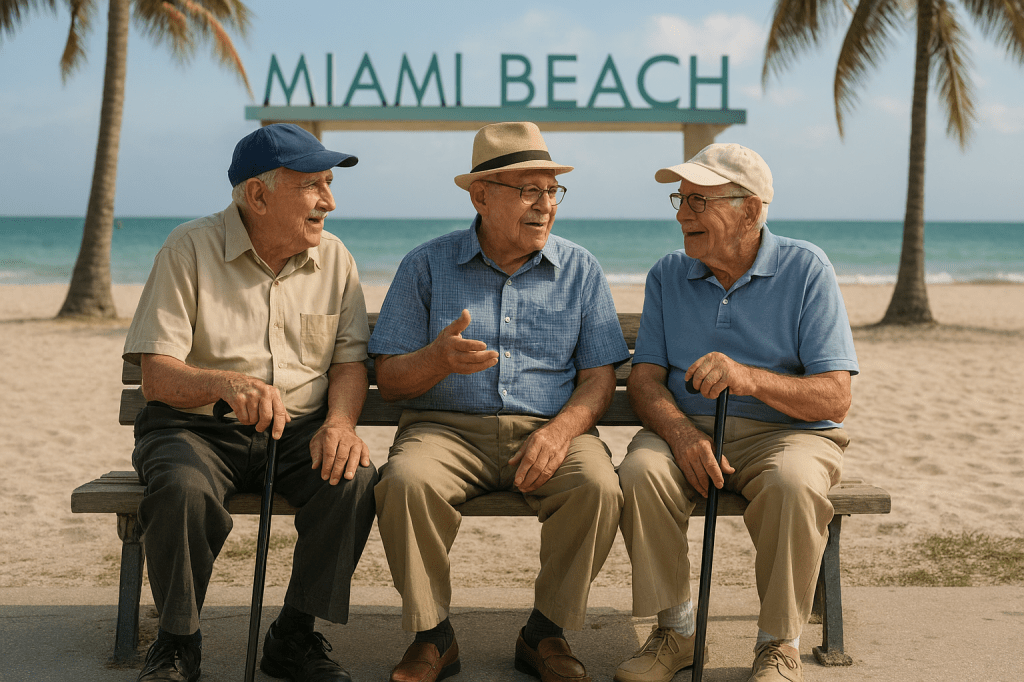

Three retirees are sitting on a bench in Florida. The first one says, “I must be getting senile. I go to the refrigerator and forget what I was looking for.

The second man says, “I know what you mean; I go into the bedroom to get something and forget what I wanted.”

The third one smiles and says, “Not me, I’m still sharp as a tack.” I remember everything; I always know where I am. My mind has stayed sharp, and knock wood…” He emphasizes his point by rapping his knuckles against the bench, then looks around and says, “Who’s there?”

First of all, why is that funny? And what does “funny” even mean? Ever wonder why we find jokes funny? “Funny” is hard to pin down. For example, when I lived in a condo in Portsmouth before I bought my house, there was always someone tailgating me and flashing their lights when I started driving into town. It got to the point where I would simply pull over on the shoulder and smile and wave as they sped past. Why the smile? I knew something that they didn’t, and that was that the reason I was driving 25 mph was that the Exeter Police usually had a speed trap just the other side of the rise. About half the time, when I caught up, the tailgater was getting a ticket at the side of the road. Now that’s funny. On the other hand, if they had driven into a tree, that would not have been funny; I wanted them inconvenienced, not dead. So what gives?

The Anatomy of Humor

Current theories about humor start with our brains being adapted cope with our environment.; finding food and water, detecting threats, figuring things out. But with jokes, just when we think we grasp the arc of the narritive. the punchline yanks the rug from under our feet. Psychologists call this “incongruity resolution”—you’re led down one garden path and, surprise, the gate opens to a completely different backyard. That twist—the “Wait, what?” moment—is what makes us laugh.

So what are we talking about when we say something is “funny”? “Funny,” to the social scientist, means anything that gives the brain momentary disorientation in a non-threatening situation through well-managed surprise. It might be a pun, physical comedy, or satire. Whether it’s a pratfall or a play on words, if it jostles the mind in a safe, clever way—it’s funny.

Theories—Because Science Likes a Good Joke, Too

- Incongruity Theory: Humor is what happens when reality zigzags and the mind gets wrong-footed.

- Superiority Theory: Sometimes we laugh because, frankly, it’s not us falling down the manhole.

- Relief Theory: Every giggle is nature’s own pressure valve. Laughter empties tension and defuses tense situations.

This is similar to other forms of art and entertainment. A good story sets up the situation (star-crossed lovers, a complicated bank heist), creates tension through conflict or peril, then resolves the conflict, one way or the other. There may be twists and turns in the story, but those have similar effects as jokes, because they are little surprises.

Ok, maybe that’s why we find things funny, but what’s with telling jokes? BTW, in talking to millennials, something finally occurred to me. They often refer to “Dad” jokes, particularly when I make them. But observing them in their natural environment, it hit me: they hardly tell jokes. It’s not that they don’t have humor, although it is different. They seem to get their laughs from randomness, which makes sense in the funny department. But they don’t stride into the room and announce, “Here’s a new one; why don’t you use three eggs in an omelet? Because two eggs are an oeuf!” Humor changes over time like language, and I finally realized that “Dad jokes” is just another term for “joke.” In the same vein, I’ve watched my son and his wife watching old musicals and sensed their bewilderment: why are these people, who were just having a conversation, suddenly singing and dancing? And taking their perspective, I get it; the idea that Gene Kelly would suddenly have a bizarre reverie that suddenly switched into a singing, dancing fantasy is something you have to grow up with.

Laughter

So humor generally and jokes specifically make us laugh. But then another thing I never considered occurred to me: what is laughter, and why does it take the form it does?

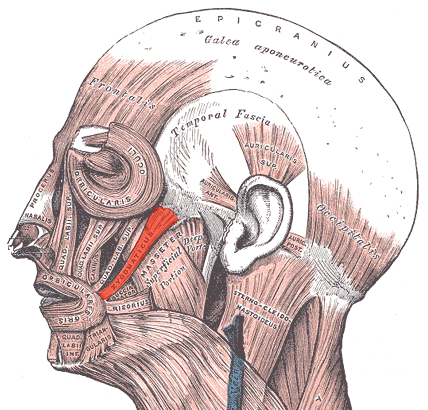

When a person laughs, several things happen all at once: the brain coordinates a whole series of muscle contractions in the face and body, starting with about fifteen facial muscles tightening and relaxing. The zygomatic major muscle lifts the upper lip, and the skin around the eyes creases, sometimes squeezing the eyes shut.

The diaphragm and intercostal muscles in the chest work in rapid bursts, which forces air out of the lungs in a series of rhythmic exhalations—those “ha ha ha” sounds aren’t just for show; they’re what happens when the epiglottis partially closes off the larynx, disrupting normal breathing and producing laughter’s peculiar noise.

Heart rate and blood pressure increase briefly, and breathing becomes irregular until the laughing stops. The brain is busy too: regions associated with emotion (the limbic system), motor control (motor cortex), and decision-making (frontal lobe) all get activated together. After a good laugh, stress hormones like cortisol drop, endorphins get released, and most people feel calmer, sometimes for nearly an hour afterwards. So laughter isn’t just a noise—it’s a coordinated event, involving muscles, breathing, and brains working together in a wave of positive physical reaction.

I was curious about whether neuroscientists had studied what happens to the brain when people laugh. It turns out that there is not a great deal of data, for a reason that hadn’t occurred to me. When you get a brain scan, it’s important that you not move, as it degrades the image. But if the neuroscientist studying you tells you a real knee-slapper, you are bound to move around some, and lots of the results they have gotten are full of artifacts from involuntary movement.

It appears that laughter is universal; members of all human cultures laugh in the same way, whether you are an Inuit, Zulu, Peruvian, or Pakistani. That being said, I’m guessing religious fanatics are not a bundle of laughs; it’s hard to imagine a card-carrying member of ISIS regaling his chums with knock-knock jokes, unless the punchline was “So the infidel was dismembered, along with all his kin!”

Animals laugh too. It turns out that laughter or something like it is seen in at least 65 species. If you’re playing with a dog, rubbing its belly and chasing it around the yard, that peculiar panting sound isn’t just labored breathing; it’s dog laughter. Rats will squeak and chirp when you tickle them, and it’s not just random rodent noise; it’s their version of giggling. Dolphins whistle and chirp at each other, and sometimes, those noises mean “this is fun, keep going!” Chimpanzees will pant and make hooting sounds when they roughhouse with friends, just like kids on the playground.

Summing up

You know, after researching this, I find that all this information, while helpful, doesn’t completely explain humor and laughter. Maybe sometimes the totality of a phenominon like love, or beauty or awe is more than the sum of its components. We see through a glass darkly, and an explanation is not the thing itself.

Okay, just to wind things up, here’s the gorilla joke. A gorilla walks into a bar and pulls up a stool. The bartender, who is chatting with some regulars, looks up and sees him. “Guys, there’s a gorilla at the bar. What do I do?” The regulars confer and suggest he ask the gorilla what he wants. He does so, and the gorilla orders a Bombay martini, straight up, with an olive. The bartender goes back to the regulars and asks, “What should I charge him?” The regulars suggest $25. The bartender gives the gorilla the bill, and without a word, he pays up and adds a 15% tip. Curious, the bartender strikes up a conversation.

After a few “How about those Yankees?” and “Nice day if it doesn’t rain,” he says. “You know, we don’t get many gorillas in here.”

The gorilla looks him in the eye and replies, “And at these prices, you won’t be getting many more.”

I can almost hear you slapping the table, gaffawing, and crying out, “Stop, stop, lest my sides split with mirth!” Don’t thank me; as I have said before, I am a river unto my people.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.