It’s a night like any other. You go to bed and drop off to sleep, but just as you start to drop off, you are jolted back into wakefulness. You hear a loud humming in your ears, and you try to sit up, but you find to your dismay that you are completely paralyzed. You struggle to move, but to no avail. It becomes harder to breathe, and now you can make out the vague outline of a shadowy creature squatting on your chest. Terrified, you fight to move but you are still unable, and that only adds to your terror. Finally, with a gasp, you break out of the strange grip that held you motionless. You sit up, shaken and sweating profusely, and find the shadow figure nowhere to be seen and your room just as it always is.

What’s going on here? Perhaps the person in this vignette has been traumatized or has some kind of emotional conflict that gets expressed through nightmares? Maybe it was that spicy meal they had before they went to bed, or that horror film they watched before retiring? Probably not. This type of nightmare is far from rare. In fact, Robert Ness, in a 1978 paper, described a fishing village in northeastern Newfoundland in which at least 10% of the population experienced such sleep disturbances. The people of the village called these attacks “The Old Hag.” The causes of these episodes and the way they are culturally interpreted by the affected population offer some perspective on the genesis of the culture-bound disorders.

The people of Northeast Harbour, which is the pseudonym he gave to the village, all report very similar symptoms when they suffer the attacks of the Old Hag. The attacks occur at night when the victims are in the process of falling asleep or just waking up in the morning. The “Hagged” individual suddenly experiences waking up out of sleep but being totally paralyzed, unable to move or speak. The victims report that they are aware of their surroundings and other people around them but find themselves unable to call out for help. People who have been “Hagged” often experience the attacks as terrifying and struggle desperately to break out of their paralysis but frequently find it difficult unless they are touched or called to by another person. Others who are affected by the syndrome are made less anxious and simply relax and allow the attacks to subside naturally.

The people interviewed by Ness made a clear distinction between simple nightmares and attacks of the Old Hag, although they do report that dreams may precede the episodes. After the attack is terminated, the victim is often left exhausted and drenched with sweat.

While they are under the influence of the Hag, some of the sufferers also report seeing ghostly people come into the room who they may or may not recognize. These spectral presences may be reported as having a weird or otherworldly aspect, and their presence is sometimes linked to the onset of the attacks. Ness reports that the Newfoundland community he studied has an active undercurrent of belief in the supernatural, and the name of the syndrome, the Old Hag, derives from legends of an evil witch or hag who would put spells on sleeping victims. Several of Ness’s older informants reported actually seeing the hag during their paralytic attacks.

Ness’s article gives several accounts by individuals in the Northeast Harbor community who experience fairly frequent attacks of the Old Hag. One individual referred to as George described the experience like this:

“I came up late from the stage [storeroom for fishing gear] We had beach stones up the path then and I went in and lay down like this [reclining in a chair] and before long I heard steps comin’ up the path on those rocks. The outside door opened, then the inner door and I wondered who was comin’ in, bein’ so late. Then I saw a woman all in white come across the kitchen. She came around the stove and came over to me. Then she put her aims out and pushed my shoulders down. And that’s all I know about it. She ’agged me.

Ness noted that George could not recognize the woman but said that he “was chasin’ a few girls around the harbour then.” He also noted that “I’ve dreamed about ‘em before and young girls have ’agged me, but I suppose they didn’t know it just the same.”

The same subject gave Ness an account of one of his more memorable Hag attacks:

I can feel it comin’ on, ya know it’s a real uncomfortable feelin’ like a fear spreadin’ over ya. I can bawl out when I have it and I can get it when I’m lyin’ on my chest, or with my hand along side. I’ll say, “Call me! Call me!” Sometime I get all tangled up with cats, horses, or fallin’ of cliffs. I was ‘agged just a few weeks ago … ya know those TV chipmunks or TV puppets or whatever you call’ em. I was watchin’ those and went to bed and they ’agged me.

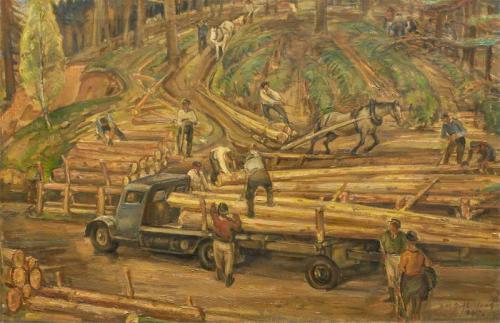

Rather than being a rare occurrence, Ness found these attacks of the Hag to be remarkably common in the small community. He collected reports of the disorder from 43 affected persons in the community of only 400, and almost everyone in the community was very familiar with the phenomenon. The informant’s theories about the causes of the disorder fell into three basic groups. Most of those interviewed on the subject felt that attacks of the Old Hag occur when the victims sleep flat on their backs because it is understood that in this position a person’s blood tends to pool and stagnate. Others in the community believed that the attacks are brought on by extreme exertion and being physically overtired. Some of the villagers who spoke to Ness told him that the Old Hag was very common in the inland logging camps, where the men worked very hard without proper rest or food.

Finally, some of those interviewed felt that the Old Hag could be “put on ya” by someone else, in the manner of a spell or curse, or by the simple fact of someone harboring anger, hostility, or envy toward the victim. As previously noted, Ness stated that the people of Northeast Harbor have close links to their English heritage and have an active body of folk beliefs and superstitions derived from their old country origins. These superstitions and beliefs are accepted to varying degrees by the villagers, but virtually everyone in the village is at least familiar with this current of beliefs.

Ness’s research showed that the people of Northeast Harbor did not regard the attacks of the Hag as a form of illness or as a condition that required treatment of any kind. They also rejected any suggestion that they should see a physician about the complaint. The Old Hag is seen more as something that simply happens to some people at certain times, like a bad dream or an attack of indigestion. Certain methods are recommended for averting the attacks by the villagers. These include avoiding going to sleep lying on the flat of the back, reciting certain charms before retiring or sleeping with a Bible under the pillow.

The Old Hag symptomology and the attitude of the people who experience it are very different from the usual picture seen in culture-bound disorders. It does not seem to have arisen out of any obvious cultural dynamics or personal issues that could be detected by Ness in the course of his investigation. As seen in previous chapters, culture-bound disorders are usually related to some emotional/cultural issue of the group that manifests the disorder. For example, Koro seems to be related to castration anxiety and generalized difficulties with the attainment of a satisfactory male identity in men who develop the disorder. But the Old Hag appears different. In this case, the symptoms are coupled with a relative lack of concern on the part of the victim, and this lack of concern is shared by the general society. This seeming incongruity raises questions about the essential nature of the disorder.

Attacks of the Old Hag appear not to be related to any serious physical malady. Ness found, through a systematic study of the health of the population of Northeast Harbor, that those who reported attacks of the Old Hag were no more likely to report physical or emotional complaints than those who did not report attacks. Because several families in the community had a higher incidence of attacks than other families, there may be inherited factors in the formation of the syndrome.

I called Dr. Ness and he was gracious enough to speak to me about his research. He told me that when he came back to the United States after completing his Newfoundland research, he was convinced that he had uncovered a unique new neurological or psychiatric syndrome, previously unknown in the annals of modern medicine. However, when he described the symptoms of the Old Hag to a fellow graduate student, he was startled when she replied, ‘Oh, I get that all the time!” Further investigation revealed that there were many people in the United States, seemingly in good mental and physical health, who reported incidents of symptoms almost identical to those of the Old Hag. Ness’s research into disorders of sleep led him to the conclusion that the Old Hag is simply a form of sleep disorder called sleep paralysis, which, while not very well understood by modern medicine, has been recognized for some time.

The experience of people with episodes of sleep paralysis in our own culture shows a marked similarity to the types of experiences reported to Ness by his subjects in Northeast Harbor. For example, Schneck (1968) reported the following symptoms in several patients he treated:

“A 33 yr. old man sought psychiatric treatment for symptoms of sexual impotence. He described his sleep paralysis from the time he was 8 to the age of 32. The episodes appeared two or three times a week on falling off to sleep, but not on waking. Many attacks involved the feeling of “someone sitting on my chest” which others with sleep paralysis also described. The squatting figure was a vauge and shadowly woman. The hallucination contributed to his sensation of suffocation. At times he would react rapidly, forcing body movement while still moaning, and thus break the paralysis.”

When thoroughly paralyzed, he would feel unable to moan, much less move. He would have to await the spontaneous disappearance of the paralysis, which, taking a minute or so, would seem more like an hour. The patient was always aware of his real surroundings during the paralytic attacks. The shadowy, squatting figure would sometimes emit a prolonged 0-0-0-0-0 …” sound. When his wife was on hand, she would shake him when she heard him moan. This characteristically dispelled paralysis.

In the same article, Schneck reports the experiences of another patient:

“A 32-year-old woman recalled five sleep paralysis attacks she had a year before seeking psychiatric treatment. They occurred within a period of one month. She believed all were essentially similar and remembered two in detail. She fell asleep in the evening and on awakening found herself completely paralyzed. She was aware of being in her bedroom. Although struggling ineffectually to move, she did not have a feeling of pressure on her chest, nor did the passage of time seem unusually prolonged. But she did have feelings of anxiety. The episodes were not terminated by a sudden movement. Instead, as an occasional patient will describe, she’ waited till she relaxed for the paralysis to disappear. During one episode, she heard footsteps in the apartment. She thought a man was walking about and assumed it was her boyfriend. When she realized that he could not be there at that time, she believed it was an intruder, grew frightened, and feared being harmed. Later she realized it was a hallucination. During a second episode, she saw a shadow cast on her bedroom door by the light in an adjacent bathroom. The shadow moved about; she decided it was not what she usually saw and again was frightened and feared harm from an intruder. Later, she realized the movement of the shadow had been an illusion.”

Sleep paralysis has been described as an unusual neurological phenomenon that presents as a brief period of inability to move or speak upon falling asleep or arising. This transient paralysis is often accompanied by terrifying hallucinations, which are distinctly different from normal nightmares in their feeling tone and in the neurological activity that produces them. The attacks of paralysis are usually quite brief (although they can seem quite long subjectively) and are aborted by the person’s struggles to break out of the state by moving or crying out, or by the person’s being touched or shaken by someone else. The patient may relapse into paralysis if they do not get up and move about before returning to sleep.

Sleep paralysis was first described in medical literature by Mitchell in 1876. The syndrome has also been known over the years by other names, such as nocturnal paralysis, delayed psychomotor awakening, and catalepsy of awakening. The syndrome has been linked to two other neurological syndromes known as narcolepsy and catalepsy. To begin to understand the possible causes of the condition, it is first necessary to learn something about the nature of normal sleep and some of the ways in which sleep can be disrupted.

For most of human history, sleep was thought to be a unitary, undifferentiated state. People were seen to simply be in an unconscious state for 7 or 8 hours every night. Research in the 1950s demonstrated that the normal sleeper passes through a number of different stages during the night, all characterized by distinct patterns of brain activity and levels of physiological arousal. In general, the various stages of sleep can all be placed in two basic categories. These are Rapid Eye Movement sleep (REM) and Non-Rapid Eye Movement sleep (NREM). REM sleep is so named because the eyes of the sleeper in this state dart up and down and side to side beneath the sleeper’s closed lids. REM sleep is also the period when most dreaming occurs. This was discovered through simply waking up sleepers during REM sleep and asking them what they were experiencing. One interesting finding of this type of research is that the direction of the eye movements (up and down or side to side) often corresponds to the direction of action reported in the dreams.

REM sleep itself has two sub-phases, called tonic and phasic REM. In phasic REM, the sleeper’s body is more active, the eyes twitch, and there is an elevation of the vital signs. Tonic REM is different from phasic REM in that nearly all of the skeletal muscles are paralyzed. Some researchers have theorized that it is this paralysis that prevents the sleeping dreamer from moving about in response to the dream and possibly injuring himself.

REM sleep itself has two sub-phases, called tonic and phasic REM. In phasic REM, the sleeper’s body is more active, the eyes twitch, and there is an elevation of the vital signs. Tonic REM is different from phasic REM in that nearly all of the skeletal muscles are paralyzed. Some researchers have theorized that it is this paralysis that prevents the sleeping dreamer from moving about in response to the dream and possibly injuring himself.

The sleeper next moves into progressively deeper stages of sleep. In stage two sleep, the sleeper is much less aware of environmental stimuli, and if awakened at this point, will report having been asleep. An even deeper stage of sleep, called Delta sleep, follows stage two. All of these phases are characterized by distinct patterns of brain activity as measured by EEG tracings and have differing levels of physiological arousal

After the first progression through stages 1, 2, and Delta, the sleeper moves back through the stages in reverse order. However, instead of going back into stage 1, the sleeper moves into the night’s first period of REM sleep, with accompanying dreams. REM sleep alternates with phases of NREM at approximately 90-minute intervals, with the periods of REM gradually increasing in duration up to the point of awakening.

In trying to understand sleep paralysis, it is helpful to conceptualize the human brain as existing in three general states: wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep. REM can be considered a separate state of neuropsychological existence because it contains elements that are characteristic of both sleep and wakefulness. For example, in REM there is eye movement and increased activation of certain physiological functions, with the accompanying mental activity that is characteristic of the dreaming state. On the other hand, the sleeper is much less responsive to environmental stimuli. It is because of these apparent contradictions that REM sleep is sometimes also called “paradoxical sleep.”

The most recent research on the subject suggests that sleep paralysis occurs due to the brain mixing up some of the sequences that occur with movement from wakefulness into REM, NREM, and back to wakefulness. Sleep paralysis occurs most frequently just as the afflicted individual is falling off to sleep or when the person begins to awaken. In normal sleep, as mentioned previously, the sleeper moves from wakefulness into stage 1, 2, and delta sleep and then into REM. In sleep onset sleep paralysis, it is theorized that the individual moves almost directly into a premature REM phase. This is followed by a return to partial wakefulness, probably similar to stage 1 sleep. However, in the case of sleep paralysis, the generalized motoric inhibition (paralysis) usually accompanies REM and does not recede with wakefulness. This same phenomenon is also seen in sleep paralysis, which occurs upon awakening in the morning, except that in this case the sleep-paralyzed individual awakes prematurely from a REM state.

When this happens, the afflicted individual becomes conscious but cannot move or call out. This is the essence of the experience of sleep paralysis. Sleep-paralyzed individuals usually struggle to move and break out of the state, and the attack terminates abruptly when the person is suddenly able to break free or when someone else touches the sleeper or calls their name. In some individuals, there is also an associated problem with breathing, and this sometimes adds a sensation of suffocation or drowning to the experience. This seems to occur because the combination of REM and waking brain activity causes a temporary disturbance of respiration.

It is easy to understand that the experience of waking up precipitously and discovering oneself to be paralyzed would be frightening. And there are other aspects of the experience that can sometimes increase the terror that accompanies the episodes. Incidents of sleep paralysis are sometimes accompanied by bizarre, frightening visions known as hypnagogic hallucinations. These hallucinations can take many forms; sometimes the sleeper sees people, creatures, or animals in the room with them, hears voices, noises such as loud humming, or the sound of bells. These hallucinations are referred to as either hypnogogic or hypnopompic; hypnopompic refers to hallucinations that occur as you are falling asleep, while hypnogogic hallucinations happen when you are in the process of waking up. More recently, the terms are often used interchangeably.

Hypnagogic hallucinations differ from normal nightmares in several ways. First, they tend to occur in semi-conscious states such as stage 1 sleep. Secondly, there is a very different feeling tone to the hallucinations. Unlike the experience of nightmares, the person experiencing hypnogogic hallucinations is usually aware of their surroundings. They have a strong feeling that they are awake; part of the anxiety comes from the fact that elements of reality and unreality are mixed and this makes the hallucinations much more disturbing. It is the combination of the sensation of paralysis and the disturbing sounds and visions that makes the experience of sleep paralysis so disturbing.

In comparing these accounts of sleep paralysis with the reports of Old Hag episodes from Northeast Harbor, it is the strong similarity of symptoms across cultures and individuals that is striking. Ness suggests that this is because the Old Hag is simply sleep paralysis under a different name. Sleep paralysis is a usually mild disorder that probably stems from some slight abnormality in the REM system. It does not seem to be a disease per se; it does not seriously affect an afflicted individual’s health or functioning in any major way. This has been seen in such seemingly divergent groups as Newfoundland fishermen and Johns Hopkins medical students.

There have been studies that have explored the prevalence of sleep paralysis in the general population. A study by Sharpless and Barber (2012) found that in the US, about 8% of the general population has experienced at least one episode and that with college students, the rate was as high as 28%.

I think it is important to mention that sleep paralysis is sometimes associated with more serious disturbances of the REM system. Specifically, it is sometimes seen as a precursor to a condition known as narcolepsy. Narcoleptics are characterized by excessive sleepiness during the day, and this pattern usually becomes more noticeable in the teenage or early adult years. The most striking symptom of narcolepsy is the tendency of the afflicted individual to suddenly fall asleep in the midst of daytime activity. The effects of these sleeping fits can range from being merely inconvenient and embarrassing to being life-threatening, as when the narcoleptic falls asleep behind the wheel of a moving car. Between sleep attacks, the narcoleptic is often very sleepy, despite the sleep provided by the attacks or by naps.

Several other symptoms help distinguish narcolepsy from other conditions that cause excessive daytime sleepiness. As previously mentioned, one of these is sleep paralysis. Narcoleptics frequently experience hypnogogic hallucinations during sleep paralysis. It is important to point out that not all those who experience sleep paralysis have or develop narcolepsy. This is particularly true if the individual develops the attacks after early adulthood. In the same way, sleep paralysis attacks that occur in the morning are less likely to be associated with narcolepsy than those that occur at sleep onset. However, a portion of those individuals who experience sleep-onset sleep paralysis with hypnogogic hallucinations may eventually develop full-blown narcolepsy and so should have their condition monitored by a physician.

The other symptom associated with narcolepsy is catalepsy. Catalepsy is a brief period of paralysis that occurs during waking hours, sometimes in the middle of some activity. Cataleptic attacks frequently occur in association with some type of excitation, such as laughter, anger, or crying. While catalepsy can be very mild and only involve minor weakness in a few muscle groups, it can be more severe, affecting the entire body and leading to sudden complete paralysis.

Narcolepsy is related to sleep paralysis in that it seems to involve an imbalance between the wakefulness system and the REM system. In narcolepsy, the REM system, with its associated dream imagery and protective paralysis, suddenly overpowers the wakefulness system and intrudes into daytime consciousness. This is similar to but far more severe than the sleep paralysis in the subjects in Northeast Harbor or the previously mentioned American case studies. In these cases, sleep paralysis episodes were not associated with either excessive somnolence or catalepsy. For this reason, the type of sleep paralysis discussed in this chapter is sometimes referred to as benign sleep paralysis.

All of this suggests that the Old Hag is not a true culture-bound disorder in the usual sense. Rather, it is one subculture’s view of what appears to be a universal human phenomenon, filtered through that culture’s belief system and worldview. However, there is a question to be answered about why the people of Northeast Harbor seem to have so many episodes of sleep paralysis. There are several possible explanations. First, Ness observed in his research that several families seemed to have a higher incidence of Hagged individuals, even by Northeast Harbor standards. This may indicate that genetic predisposition may exist for the disorder. If this is the case, it may be that the people in this area, which is isolated, may be somewhat inbred and may have a greater probability of passing along this predisposition. In addition, Ness has suggested that the lives of the people of Northeast Harbor may also increase the probability of their having sleep paralysis attacks. Previous research has suggested that people who are deprived of REM sleep tend to have more sleep onset REM when they go to sleep. The longest REM periods of the night are usually at the end of sleep, toward morning. The men of Northeast Harbor generally work as woodsmen or fishermen, and both of these occupational groups arise very early in the morning. Ness also points out research findings that demonstrate that intense physical activity increases the proportion of NREM sleep during the night.

Both fishing and forestry are occupations that are extremely physically demanding activities. The combination of early awakening and physical exhaustion may tend to make many of the men of Northeast Harbor chronically REM deprived, and Ness suggests that this situation increases the likelihood of sleep paralysis in that population. It may be that the combination of some type of genetic predisposition and chronic REM deprivation may be what makes the disorder so frequent in that area. The specific imagery that accompanies the attacks of the Old Hag has an interesting background. The people of Northeast Harbor have a close historical link with their cultural roots in the British Isles. There is a long tradition in Celtic mythology of legends that deal with the figure of the hag.

Hags were said to be evil, ugly old women who were in league with the forces of evil. The word hag comes from the Middle English “hegge” and the Germanic word “hexe,” both meaning witch. Hags were said to visit their victims at night while they slept. Legend has it that they would sit on their victim’s chest or stomach, making it difficult for the sleeper to breathe. Many stories tell of hags riding their victims like horses throughout the night, leaving them exhausted in the morning. As a result, the term “hag-ridden” has come into the language to denote a person who is weighed down and tormented by worries or concerns. The concept of a malevolent night spirit who torments sleepers is widespread. A legendary type of night creature related to the Hag is the succubus, with its male counterpart, the incubus. These spirit creatures would come to sleepers in the night, perching on their chests, stopping their breathing, and troubling their sleep with evil dreams. Our word for troubling dreams, “nightmare,” is derived from the Old English word for incubus, “mare.”

The incubus and succubus would sometimes have sex with their victims, and there are many tales of demon lovers who came in the night throughout the legends of the world. It was thought that children with birth defects or multiple births were the results of such couplings. It is also said that ·Merlin, magician to the legendary court of King Arthur, was the offspring of an incubus.

These legends match well with the symptoms associated both with attacks of the Old Hag (as is seen in Northeast Harbor) and the general symptomology of sleep paralysis. This seems to suggest that the legends about hags with supernatural powers may have developed out of the experience of sleep paralysis. Why the imagery of sleep paralysis involves a malevolent feminine figure is not clear. It may be that such images come from infants’ experiences of being held too tightly by their mothers, and that this association passed into the common symbolic vocabulary of mankind as an unconscious metaphor. In addition, it is not uncommon to see images of suffocation in the dreams and associations of psychotherapy patients who have experienced their mothers as overprotective and interfering with the development of an independent identity. The metaphor in these cases seems to revolve around the patient’s deep feeling that they cannot draw a free breath, and psychologists writing about the subject have sometimes referred to the constricting quality of the affection of these mothers as “smother love”.

Personal dream symbols and folklore, which can be seen as the collective dreams of a culture, are distillations of common human experiences. It is possible that the figure of the old hag represents a sort of collective symbol of experiences where individuals feel their freedom to act and general autonomy being strongly curtailed. This is true whether freedom relates to individuals who are oppressed by financial or social concerns, individuals who are having problems with the formation of a personal identity, or at a very basic level, the inability to move or even breathe independently. The common human experience of constriction and paralysis (real or metaphoric) is translated by our unconscious minds into symbols that may not be consciously understood but have a deep meaning on a level below conscious thought. In the same way, the specific form of the Old Hag syndrome is what results when certain neurologically based symptomology is filtered through the individual consciousness shaped by personal and cultural experiences.

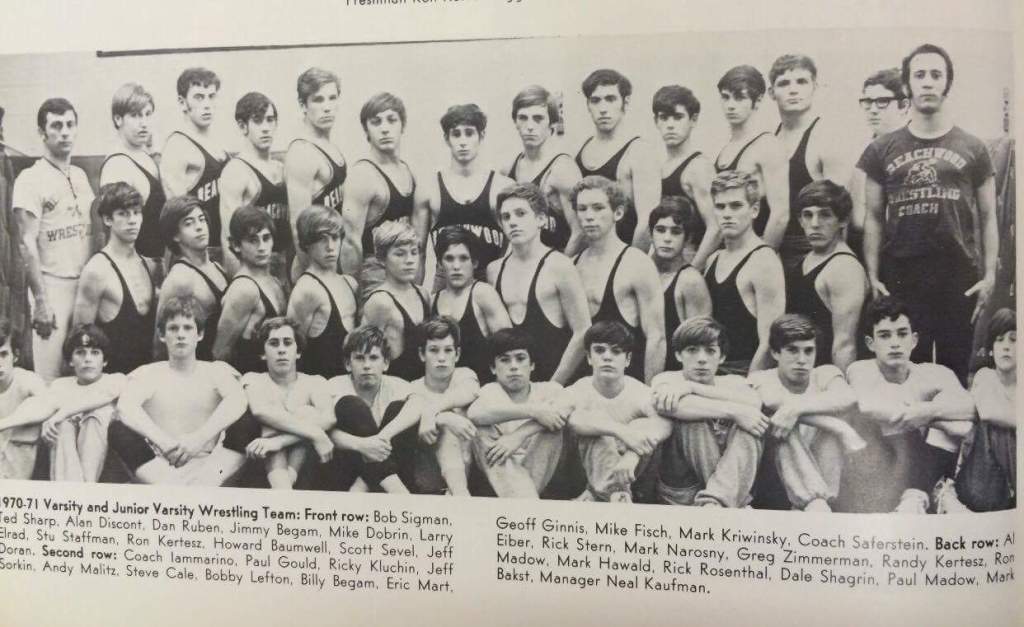

Time for a little self-disclosure, as we say in the psych biz. When I was around 16, I started having occasional episodes of sleep paralysis. In those days I was on my high school’s wrestling team.

From November until spring, it was 2-3 hours of practice 5 days a week, and during the actual season, we’d wrestle again on Friday or Saturday night. All high school sports are demanding to a certain extent, but there is nothing to match wrestling. Practice would start with some stretching, then the calisthenics would start. By mid-season, we’d be doing 100 push-ups, 100 sit-ups and 75-100 up-downs. What are up-downs? The team would space themselves out on the mat and start running in place. The coach would gesture left, right, forward and backward, and we’d follow, feet pumping furiously. Then, at random intervals, he’d blow the whistle and that was the signal to throw ourselves face down on the mat, then we’d scramble to our feet and do it again and again. It never got any easier, and that was just the warm-up. Then there would be wrestling drills. One of my least favorites involved one guy getting on the mat and wrestling 3 or 4 guys in a row for 30 seconds, until the coach blew his whistle, and a fresh guy jumped on you. After a few minutes of this, we would crawl to the edge of the mat and lie there, gasping for air and perspiring heavily. Then there would be actual wrestling matches until practice was over and we staggered home.

Added to this was the pressure to cut weight. These days, they have put a limit on how much weight a wrestler can lose to compete in a weight class. My normal weight in those days was about 145 pounds, but I wrestled in the 138-pound class, which meant that I had to lose 7 pounds if I was going to be 138 by weigh-in time, and I didn’t have much body fat in those days. We’d all starve ourselves, but at least 2-3 pounds of that was water weight, so the last couple of days involved a considerable amount of dehydration. In some cases, we would buy rubber suits, put on a couple of sweatsuits and jog in place in the boiler room. I recall that on several occasions some of my teammates and I would be spitting into cups on the bus to the meets just to be sure we made it to the weight limit. I was bumped up to the varsity in 10th grade because the older guys in my weight class managed to put themselves into the hospital when their kidneys started to shut down. I still can’t help but wonder what our parents were thinking while all of this was going on. In any case, by Thursday or Friday we were probably as tired and hungry as any Newfoundland lumberjacks ever were.

Around this time, I started to develop asthma. It wasn’t a bad case, but it caused me to convert from side-sleeping to sleeping on my back, propped up on a couple pillows. It was around this time I started having episodes of sleep paralysis, although I didn’t know what was happening at the time. I’d be drifting off to sleep when I seemed to wake up. I couldn’t move and it was hard to breathe. I wasn’t sure if I was having a nightmare, or if I was awake, but it was terrifying. I’d struggle against paralysis and try to cry out, but I couldn’t move. I’d hear a loud humming or what sounded like bells tolling and then I’d see shadowy figures out of the corner of my eye. Finally, I’d somehow break free, panting and soaked with sweat. Sometimes I’d be afraid to go back to sleep, but I seldom had more than one episode per night. I never told my doctor or my parents, and it pretty much stopped when I left for college. Looking back, I’m not sure why I never mentioned it to anyone; maybe I thought it was just nightmares. Luckily there were no apparitions squatting on my chest, but those episodes were about as frightened as I’ve ever been.

What I find interesting about my own experiences with the Old Hag is how well they lined up with what Ness and others described: paralysis, hallucinations, and strange background noises, and this was before I had any inkling that it wasn’t just me. I suppose I didn’t experience the whole hag/succubus thing because that wasn’t part of my culture; looking back, I’m surprised that it didn’t involve some spirit telling me to study harder so I could get into medical school, but I got plenty of that in the daytime.

McNally RJ, Clancy SA. Sleep paralysis, sexual abuse, and space alien abduction. Transcult Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;42(1):113-22. doi: 10.1177/1363461505050715. PMID: 15881271.

Ness RC. The Old Hag phenomenon as sleep paralysis: a biocultural interpretation. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1978 Mar;2(1):15-39. doi: 10.1007/BF00052448. PMID: 699620.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.