Back when I was researching unusual psychiatric symptoms, I came across a group of diagnoses that have been referred to as “culture-bound” disorders. The term refers to specific types of disorders that occur only in a specific culture, and they tend to be caused by a specific pattern of symptoms that only occur or make sense in a particular cultural context. There are plenty of them; there is running amok, which is a real disorder rather than a general term for losing it and getting violent; kayak angst, which only appeared among the Inuit in Greenland; and Lahtah, seen primarily in the Malay archipelago. But let’s start with a disorder called Koro.

The area of Southern China, Indo-China, and the Malay Archipelago in particular seems to be fertile ground for these types of disorders. The reasons for this are not clear, but it may have something to do with the cultures in this area being very ancient and isolated from the rest of the world until relatively recently. One of the most unique and well-known of the culture-bound disorders of this region is known as Koro, or Su-yang. A male afflicted by this disorder becomes terrified that his penis will suddenly shoot up into his stomach, causing instant death. To understand the genesis of this disorder, it is first important to know something about the cultural context in which it develops.

Eastern and Western cultures have profoundly different worldviews. Many scholars have examined these different philosophies, and the books and treatises on this subject could fill a good-sized library. Unfortunately, I took very few philosophy courses in college, and truth to tell, I slept through most of the classes. So please bear with my whirlwind tour of Eastern philosophy and take it for what it’s worth; I’m better with the clinical part of the analysis. The cultural differences between these views of the cosmos and man’s place in it are not superficial; they involve fundamental contrasts.

Generally speaking, Western man sees the world in terms of opposing forces that strive for dominance. Humanity is seen as separated from the creator by its sinfulness; good opposes evil, and man opposes nature. Eastern thought follows different lines. Rather than seeing forces in opposition, Eastern cosmology sees the world as a place where opposing forces ebb and flow, naturally seeking balance but always in a state of change. This worldview, derived from Taoism, is a more dynamic way of looking at humanity and its place in the universe. This philosophy is symbolized by the yin-yang ideogram. Its two parts represent the dual forces that encompass the universe. The Yang force is masculine, dry, and active, while the Yin force is feminine, moist, and yielding. Each of these “fish,” as they are sometimes called, that make up the ideogram contains a small portion of the opposite force. Even men and women are not seen as exclusively masculine or feminine but rather as having one force predominating over the other. This is in keeping with the Taoist idea that nothing on earth is all yin or yang exclusively. The Chinese system of medicine is based on the idea of a harmonious balance of forces in the body. Illnesses can result from excess yin or yang, and when such an imbalance is diagnosed, steps must be taken by the physician to put the body’s systems back into harmonious balance. Various herbs and animal substances (powdered deer antlers, tiger sinews, wine with snake venom) may be prescribed to alter the patient’s yin-yang balance. Acupuncture may also be applied to stimulate the flow of vital energy, called chi, through the natural meridians of the body. Systems of exercise such as Tai Chi are used to stimulate and balance the vital body energies. The yin-yang forces are also seen to affect human sexuality.

In this system of medicine, it is thought that a beneficial exchange of yin-yang energies takes place between men and women during normal sexual intercourse. The sex act is therefore usually seen as health-promoting by traditional Chinese doctors. Unfortunately, nocturnal emission and masturbation are thought to be harmful since they cause the release of yang, or masculine energy, with no corresponding “recharge” of yin energy. The result of these “unhealthy” sexual outlets is a deficiency of yang in the male. Traditional Chinese medicine also held that sexual excess in general was bad for men because it dissipated vital chi energy. This is the context in which a culture-bound disorder called Koro is seen.

Koro is a culture-bound mental syndrome that has been observed in southern China, southern Asia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. P.M. Yap, who was the leading authority on culture-bound disorders, suggested that the syndrome was spread through southern Asia by Chinese migration to that area. He points out that the word koro means “turtle head” in Malay. This is significant because the ancient Chinese poets and artists used the turtle as a symbol of long life and the conservation of vital forces. Later, the term came to refer to the penis itself, partly because of the oft-remarked-on similarity of the glans penis and the turtle head. Yap comments that a medical treatise from the Ming Dynasty discussed ways of prolonging life in males through sexual techniques that involve the practice of achieving orgasm while holding back the ejaculation of semen. The author of this treatise used a symbolic comparison of this practice to the retracting of the turtle’s head into its shell. It can be seen that ideas of sexual energy, the penis itself, and the turtle’s head are all bound up in the Malay word for the syndrome.

Koro syndrome is characterized by a morbid fear on the part of the afflicted individual that his penis is retracting into his abdomen. This creates intense anxiety in the Koro sufferer because it is generally believed that if the penis actually recedes entirely into the body, the victim will die. This belief that there is a real possibility that the penis can shoot up into the body was very strong in the recent past and continues to persist to this very day. Van Wulffen Palthe (1936) reported that in southern China and Malaysia, it was not uncommon to see male children wearing small weights on their penises to prevent sudden retraction or having relatives perform fellatio on them when they were threatened by illness.

An episode of Koro can be triggered by a number of different causes. In some cases, Koro begins when the victim overreacts to a natural decrease in the size of his penis, such as during urination on a cold night or when taking a bath. At other times, an attack can result from sexual arousal, coitus, or coitus interruptus. While the onset of the syndrome varies, the course of the symptoms is fairly uniform. The patient, believing that his penis is retracting, becomes panicked, sometimes experiencing palpitations, cold sweats, and even shortness of breath. The patient then seeks desperately to keep the penis from disappearing into his body.

Koro sufferers have been very inventive in the means they use to halt the shrinking process. The most obvious and common approach is to simply hold on firmly to the afflicted member, and many Koro patients do in fact present themselves at the hospitals with their penises clutched firmly in their fists. At other times, relatives of the victim hold the penis for the sufferer. In some cases, mechanical aids such as clothespins, chopsticks, rubber bands, and various forms of clamps are used. Folklore suggests that the very best aid of this kind is the carrying case made to contain a jeweler’s balance called a Lie Teng Hok, perfectly shaped for its new purpose. Unfortunately, some Koro victims clamp the penis so tightly that real physical and neurological damage is done to the member. At other times, the victim’s spouse performs fellatio to stop the shrinking process. Sometimes a red string tied around the base of the organ is sufficient to calm the Koro patient, red being considered a color that averts malignant influences. In any case, “first aid” is applied, and the Koro sufferer is usually taken to a traditional doctor or to a Western-style hospital in a state of considerable distress.

The following case report (Rin, Hsien, 1965) illustrates some of the central features of Koro:

T.H Yang, a 32-year-old single Chinese cook from Hankow in Central China, came to the psychiatric clinic in August 1957, complaining of panic attacks and various symptoms such as palpitations, breathlessness, numbness of the limbs, and dizziness. During the months prior to his first visit, he had seen several herbal doctors who diagnosed his disease as Shenn-Kuei, or “deficiency in vitality,” and prescribed the drinking of a boy’s urine and eating human placenta to supply chi (energy or vital essence) and shiueh (blood), respectively. At this time the patient began to notice that his penis was shrinking and withdrawing into his abdomen, usually a day or two after sexual intercourse with a prostitute. He would become anxious about the condition of his penis and eat excessively to relieve sudden intolerable hunger pangs… In July 1957, he had his first attack of breathlessness and palpitation. He felt dizzy and suffered from weakness in limbs and muscular twitching. He also complained of dryness of the mouth, nausea, and vomiting. Physical examination was largely negative; he was given vitamin B injections. He recovered in two weeks, started going to brothels again, and had another attack within a few days. Attacks came on more frequently and lasted longer…

Almost irresistible sexual desire seized him whenever he felt slightly better, yet he experienced strange “empty” feelings in his abdomen whenever he had sexual intercourse. He reported that he often found his penis shrinking into his abdomen, at which time he would become very anxious and hold onto his penis in terror. Holding his penis, he would faint, with severe vertigo and pounding of the heart. For four months he drank a cup of torn-biann (boy’s urine) each morning, and this helped him a great deal. At night he would find that his penis had shrunk to a length of only one centimeter, and he would pull it out and then be able to relax and go to sleep. The patient was overly concerned with his body and would present himself at the emergency clinic frequently, in a state of panic, with various complaints and requests for laboratory examinations to prove that his illness was somatic… His description of his symptoms was very exaggerated: “Hands tremble, anguish in abdomen, penis withdrawing, heart pounds kag-kag, kazu-kazu, I am scared… I cannot breathe at night, my heart pounds; my head aches if I talk too much; my heart sounds kok-kok; my head sounds zuzu-zuzu.”

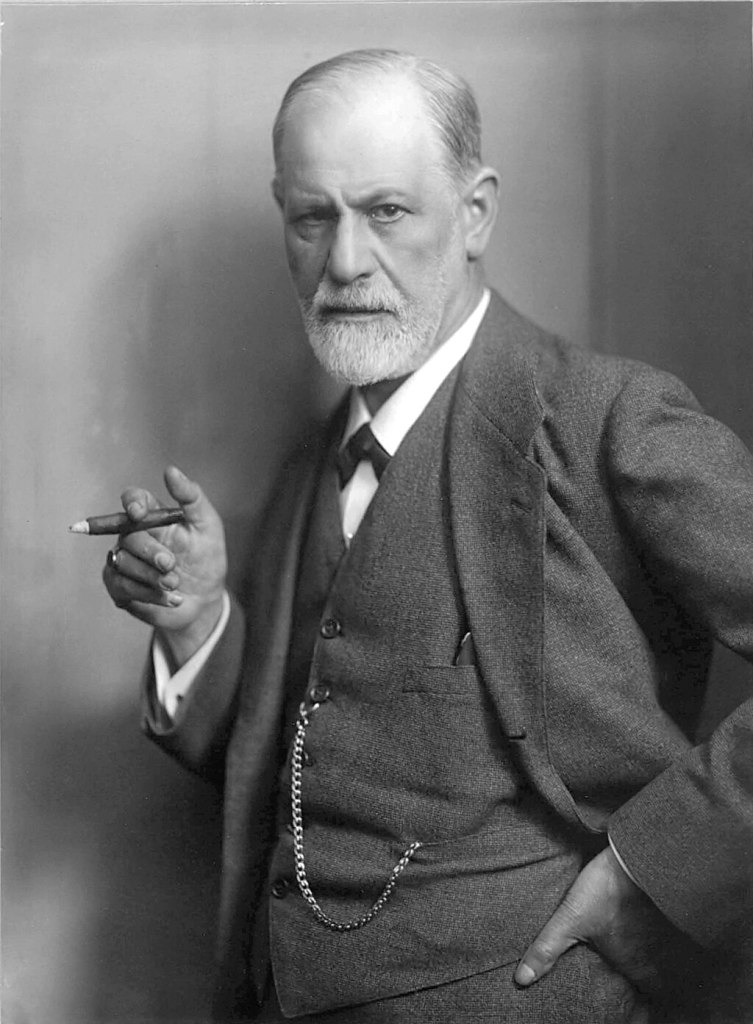

Many of the early formulations of Koro drew heavily on psychoanalytic thinking. Back in the 80s when I first started researching the subject, I was going through my psychoanalytic phase; I’m one of the few people I know who actually went through psychoanalysis. It happened like this. My doctoral program at Yeshiva had a psychotherapy requirement and they worked with the William Alanson White Institute on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I went into my intake interview expecting to be offered the usual 1 time per week psychotherapy plan that all my classmates received. To my surprise, I was offered option B, which was 3 actual psychoanalysis sessions per week on the old Freudian couch, just like in the movies. The price was right; they charged me $8.00 for a session, which a pittance even then. I was what was referred to as my analyst’s control case; he did the therapy, and he was supervised by Silvano Arieti, a professor of psychiatry at New York Medical College who won the National Book Award is Science in 1975 for his Interpretation of Schizophrenia. It was a pretty good deal. My only question was whether they picked me for the works because I was an unusually interesting subject, or whether they thought I was particularly screwed up and needed intensive treatment; I like to think it was the former, but I don’t think I’ll ever know. Psychodynamic principles are still important in my work with my own patients, but psychology has moved on and now has a cognitive/behavioral approach.

Freud introduced the concept of male castration anxiety. He believed that the male child eventually realizes on some level that his parents share a sexual relationship that he cannot be part of. At this point, the male child begins to see his father as a rival for the affections of his mother, and he starts to fantasize an end to his father’s sexual power, i.e., castration. Unfortunately, to the unconscious mind, fantasizing about an act is the same as committing the act, and the Oedipal-stage boy begins to fear retaliation in kind from his father. This fear of equal retribution for a crime is well known in world literature and custom and is known as the talion principle. This idea can be seen in its most basic form in the Bible, where the stricture “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” outlines the legal and moral precepts of the day. Freud felt that eventually the male child resolved his Oedipal complex by identifying with his father. Put more simply, the male child, realizing that while he cannot have his mother’s exclusive love, begins to understand that by following his father’s example (identification), he can eventually have a relationship that approximates the one his father enjoys with his mother.

This idea has become less important in psychotherapy as time went on. Some of the criticisms that have been raised about the concept include:

- Masculine bias: The focus on the actual sex organ as the source of most psychopathology gives short shrift to femininity, and seems to focus on heterosexuality and ignore other gender identities

- A general underemphasis on factors other than biology (e.g., the roles of social and psychological factors) in the development of personality

- Lack of empirical evidence for the concept, which is a general criticism of psychoanalytic thought

All of this may be true, but the fact remains that people suffering from Koro seem pretty preoccupied with the idea that they may lose their “manroot” (as they sometimes say in bodice-ripping romance novels) and if that is not a form of castration anxiety, I don’t know what is. With that in mind, let’s explore the concept.

One of the classic psychoanalytic case studies of castration anxiety is Freud’s analysis of a phobic reaction in a little boy. This case is known as the case of “Little Hans.” Little Hans developed a fear that if he went out on the street, a horse would bite him. Freud came to the conclusion that little Hans’ fear of horses, which the boy saw as powerful and masculine, was a displacement of the child’s unconscious fear of being castrated by his father. Little Hans developed this fear as a result of his incestuous desire for his mother.

Coming to terms with this primordial love triangle is referred to as resolving the Oedipal complex, and it can be resolved with varying degrees of success. However, according to Freud, the fear of castration that the male child experiences is very powerful, and the experience invariably leaves behind a residue of fear, known as castration anxiety, that remains throughout the life span. While there is very little experimental evidence to prove the existence of castration anxiety, there is a great deal of anecdotal evidence to suggest that it does exist in some form and exerts an influence on the male psyche. For example, almost any experienced R.N. will attest to the fact that when little boys who have had their tonsils removed come out of anesthesia, the first thing they do is grasp their penises, as if to reassure themselves that it remains intact. In psychoanalytic terms, putting a male child to sleep on the operating table to “cut something away” is a situation that is almost certain to provoke castration anxiety, and the post-operative reaction of these boys tends to bear out the assumptions of the Oedipal complex.

In virtually all cases, the symptoms of castration anxiety in Western society are expressed in disguised form, since the sexual desires that create the scenario for this form of anxiety are strongly repressed. Many theorists who have considered the Koro syndrome have related the symptoms to castration anxiety. Why Koro sufferers express their fear of castration (loss of the genital organ) so overtly, while Westerners express it through disguised symptoms, is not entirely clear. In an early article on the subject. Fritz Kobler (1948) suggested that the fact that almost everyone in the culture believes that the penis could disappear creates an atmosphere where the Koro symptomology can be openly exhibited. In such a cultural milieu, the overt expression of this form of castration anxiety need not be as strongly repressed. But regardless of how disguised or openly expressed the dynamic is, there can be little doubt that castration anxiety is the central psychic theme of Koro.

The men who become Koro sufferers vary in their personality structures, but they seem to have certain characteristics in common. First of all, Koro patients tend to come from the lower socio-economic classes and have relatively little education. Most studies of Koro patients indicate that men who eventually develop the syndrome had a variety of neurotic manifestations before the onset of their illness. Their pre-morbid adjustment was poor, and these men can be characterized as shy, dependent, and nervous. Their level of social and sexual adjustment in particular tends to be unsatisfactory. Yap (1964) reported clinical examples of Koro patients who, before the onset of the illness, were teased by local girls because of their extreme shyness, insisted on staying with their mothers at all times, and were also often very dependent on other family members. Some Koro patients managed to find wives but often simply transferred their dependency needs to their spouses.

Yap and other authorities are almost unanimous in their characterization of Koro patients as having a poor level of sexual adjustment. Many patients were reported to use masturbation as their only sexual outlet because they feared catching a venereal disease from women. Others had unsatisfactory sexual relations with their wives and used masturbation to relieve the attendant sexual tension. There are also clinical reports that some Koro patients manifested their sexual difficulties through hypersexuality. Yap reports that some of the patients he treated were married and visited prostitutes and masturbated frequently before their first Koro attacks. The underlying dynamic for virtually all reported cases seems to be a fear on the part of these men that they had been excessive in their sexual activities. Loss of male potency and virility is a serious concern in all Koro cases.

The theorists who have explored the Koro syndrome have come to differing conclusions about exactly what category of mental illness Koro belongs in. Some theorists have seen it as a kind of anxiety neurosis; others have characterized it as more akin to a phobia or panic state. Yap (1965) made an interesting comparison between Koro and psychiatric conditions known in the West as conversion reactions. Conversion reactions are seen when an individual expresses a psychic conflict through a change in the functioning of some part or process of the body. Conflicts between sexual and aggressive impulses and the individual’s ideas of morality (his conscience) are symbolically expressed through a physical metaphor. Norman Cameron (1967) gives the following examples of conversion reactions:

A college student went numb in his hands and arms after failing his examinations. This cleared up when he found work, but it returned when he took entrance examinations later in another college and again just before graduation. The numbness did not correspond in distribution to that of sensory nerves.

A middle-aged woman lost her voice following a long-distance call from her mother, when she learned that her mother was dying. All medical examinations, including bronchoscopy, were negative. She recovered her voice spontaneously after a period of mourning.

At the age of eighteen, a young man was struck in the eye by a snowball. He was experiencing general unpopularity among his classmates when this happened. He now found that he could not see and therefore could not study or remain in school. Whenever he sought work, over a period of four years, he would become functionally blind. He mixed well with his friends who were working, and, though jobless himself, he seemed content with his lot. As long as he did not try to work or study, his vision remained normal.

The part of the body affected in conversion reactions usually has a symbolic significance for the patient. For instance, in the case of leg paralysis, the patient may be expressing ambivalence about leaving home or a conflict between dependence and independence, metaphorically making the statement that he cannot stand on his own two feet. The same thing is seen in conversion blindness; in these cases, the patient may be physically expressing guilt about seeing (or realizing) something about which he feels conflicted. In these cases, the patient is not consciously malingering. Instead, he experiences himself as having a physical disability. Substantial secondary gain is frequently associated with these symptoms. Expressing conflicts through conversion reaction frees the sufferer of responsibility for his actions; it is not his “fault” that he cannot work or leave home; it is his physical disability that is to blame. These conditions also supply the added secondary gains that go along with the role of the sick person in society, such as special care and reduced responsibility.

There are a number of ways in which the clinician can differentiate conversion reactions from real organic illnesses and conditions. It is particularly easy to do in the case of conversion anesthesias, which are conditions in which an area of the body loses all feeling and becomes numb. Two common patterns seen in conversion anesthesia are known as glove and stocking anesthesia. They have been given these names because the area in which the loss of feeling takes place corresponds to the areas covered by these two garments. Patients affected by these conversion reactions demonstrate loss of sensation in the hands that stops at the wrists, the wrists, or the feet that stops at the ankles. It is easy to diagnose these anesthesias because the pattern of numbness does not correspond to the pattern of the nerves in these limbs, so such a pattern of anesthesia could not possibly result from an injury or physical illness.

Yap felt that some of the symptoms of Koro were caused by a conversion anesthesia of the penis. He suggested that the Koro patient, having grave doubts about his virility and masculinity, express this uneasiness as a conversion reaction. a conversion reaction. In this case, he would lose part or all of the sensation to this organ, and this would stimulate feelings of panic that his penis was actually disappearing. The fact that an indigenous body of folk beliefs supports and gives credence to this feeling prepares the patient to jump to the conclusion that he is suffering from Koro and adds to his panic.

This scenario of the genesis and course of Koro is in keeping with some of the clinical observations that have been made about conversion reactions. In modern times, there has been a marked decrease in the number of cases of conversion reactions, which are seen yearly by clinicians. One of the possible reasons for this decline may be the greater sophistication of the public in recent years. The idea that a person might develop paralysis, blindness, or some other physical problem because of some mental condition is no longer exotic or unbelievable. Television dramas and soap operas use these conversion reactions as elements of their plots and often use even children to understand that sometimes a physical condition can be “all in the mind” of the sufferer. This level of sophistication makes it more difficult for the individual to make use of these mechanisms, since they now know better than to accept the symptoms at face value. In fact, anyone who has read the preceding explanation of glove anesthesia is very unlikely to develop the condition. Additionally, those around us also “see through” such symptoms and are therefore less likely to supply the secondary gains (care, sympathy, etc.) that used to be part of the pay-off.

All this has meant that conversion reactions have become less frequently seen in the psychiatric population. The only places where conversion reactions are still seen with any frequency are areas where there is a very low level of education and psychological sophistication, such as the more isolated parts of Appalachia or the urban ghettos. This pattern also holds for Koro, since it is usually seen in the poorer and less educated classes of South China and Indochina. However, there is evidence that recent increases in the education level of the population in these areas have reduced the incidence of this disorder. This is illustrated by a monograph by Dr. Chong Tong Mun, which appeared in the British Medical Journal issue in March 1968. He reported that in October and November of 1967, a panic swept Singapore. The panic was brought on by rumors that the eating of pork from pigs that had been recently vaccinated for the swine flu would bring on Koro. This rumor caused a panic, and a Koro epidemic began. Dr. Mun reported that hospital clinics, which usually saw only a few cases per year, were now swamped by 80 cases a day. Not surprisingly, the sales of pork at butcher shops and restaurants came to an immediate standstill. The acute cases were treated with minor tranquilizers such as Valium and reassurance from their physicians. This was usually enough to end the attack. However, the local health authorities went on the offensive, giving public talks and press conferences to explain that there was no health hazard in the eating of the vaccinated pigs and certainly no risk of Koro. This informational campaign had the desired effect, and the incidence of Koro declined rapidly in the subsequent months. These events bear out the theory that increased knowledge of disease processes may decrease the incidence of more primitive psychological disorders like Koro and also reinforce Yap’s formulation of Koro as a culture-bound conversion reaction.

Most authorities on the subject have stated that Koro has been less prevalent in recent years. However, I have strong anecdotal evidence that the belief in the syndrome still exists in parts of southern Asia. I was recently eating lunch in a Chinese restaurant in Cincinnati, reading an article on Koro between courses. While serving me my wonton soup, the Asian waiter glanced at the article and noticed the words “Su-yang” in Chinese. He told me that he was from Singapore and that he knew all about the fact that the disease was still a very common condition. He told me that the disease was that he and many of his friends went to herb doctors to obtain potions to stave off the dreaded malady. He even stated that a good friend of his had recently died from Koro. Fascinated, I asked for more details. He told me that his friend had been having sex with his new bride when the attack occurred. The attack was brought because his friend had stood under a fan after sex, and the chill, combined with the loss of chi energy from coitus, precipitated the attack. His friend developed severe stomach cramps, and his jaws locked shut. A few minutes later, the poor man’s penis began receding into his stomach and his skin turned a hideous black color. A few moments more, and he had expired. My informant also told me that if you call a Western-trained physician in this situation, you are as good as dead, since only herbal medicines and acupuncture could save a man from an acute case of Koro. He also mentioned that experienced women usually made love with a silver pin in their hair for just such an eventuality. These women know that if their lover develops signs of Koro, the attack can be averted by sticking the pin into the acupuncture point at the base of the spine. This somewhat drastic remedy would keep the man alive until professional help could be summoned. I have no idea how representative the waiter’s views on Koro are, but I did find a translation of an old Chinese medical text that gave almost exactly the same formulation of Koro that he did. This same text also gave directions for the formulation of a medicine that would help the Koro patient, the main ingredient of which was a powder made of the ashes of burnt panties

Koro is another example of how cultural dynamics can interact with individual personalities to produce specialized psychopathology. In this particular case, the sexual folklore and general worldview of the southern Asians created the fertile ground for this syndrome to develop to its present form.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.