Ever since I became a psychologist, I’ve been fascinated by some of the unusual diagnoses and syndromes that lurk in the dark corners of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, 5th Edition (DSM-5) and academic databases. At one point I even started a book on the subject, but life got in the way and it was never finished; maybe I’ll finish it when my practice winds down at some point. But most people and the majority of psychologists have either not heard of these diagnoses. That’s a shame, since not only are they very interesting, they also raise questions about the nature of human consciousness and mental disorders. That being the case, I’m going to post about these disorders now and again. Let’s start with:

Capgras Syndrome

Imagine the following scenario:. After a day at the office and a quick workout, you come home around 6:30, pretty typical for you. You hang up your coat, and you hear your wife of 20 years moving around the kitchen, getting dinner ready. You call out “Honey, I’m home!” like you do every night. You enter the kitchen and go to give your wife a hug; she pulls back, an expression of perplexity and anger on her face.

“What have you done with my husband?” she demands.

“Honey, what are you talking about?” You wonder if she’s joking, but this isn’t really her style.

“Don’t ‘Honey’ me. You look like Jacob, but you can’t fool me.” She grabs a knife from the counter and walks purposefully toward you. You decide that it’s not a joke at all and quickly run out of the house, calling 911 when you get to the tree lawn. As the ambulance arrives, you wonder: has your wife been poisoned or drugged? Is she ill? She seemed fine when you left for work; what’s going on? The EMTs try and talk to her, but she keeps shouting about her husband having been replaced by a replicant. They have to restrain her, load her onto a gurney, and place her in the ambulance, still shouting and demanding she be released so she can find her husband, who has obviously been kidnapped.

What’s going on here? Why has this man’s wife become convinced he is an imposter and become violent? Is it some kind of brief, sudden psychotic break? It could be, but in this case it is something called Capgras syndrome. It was first identified by Jean Marie Joseph Capgras, a French psychiatrist who was most active in the early 1900s. He and his co-author, Jean Reboul-Lachaux described a woman who believed she was wealthy, famous, and a noble. Three of her children had died, but she insisted they had been abducted and that her only surviving child had been replaced by an identical imposter.

What Imaging Can Tell Us

I first started practicing psychology in the late 80s, so I’ve been at it for over 40 years. There have been some advances, but I think one of the most dramatic is the advent of imaging techniques that allow neuroscientists to see the brain functioning in real time. Its complicated, but let me use a simple example. Researchers could identify a group of adolescents with ADHD as well as a matched group (similar age, IQ, socioeconomic class). Then they put members of the two groups in the imagining device and have them engage in a task requiring sustained attention. These advanced techniques allow the researchers to see differences in how the brains of both groups respond to the task. This allows researchers to develop theories about how the brains of the adolescents with ADHD process information differently from those who don’t have the disorder.

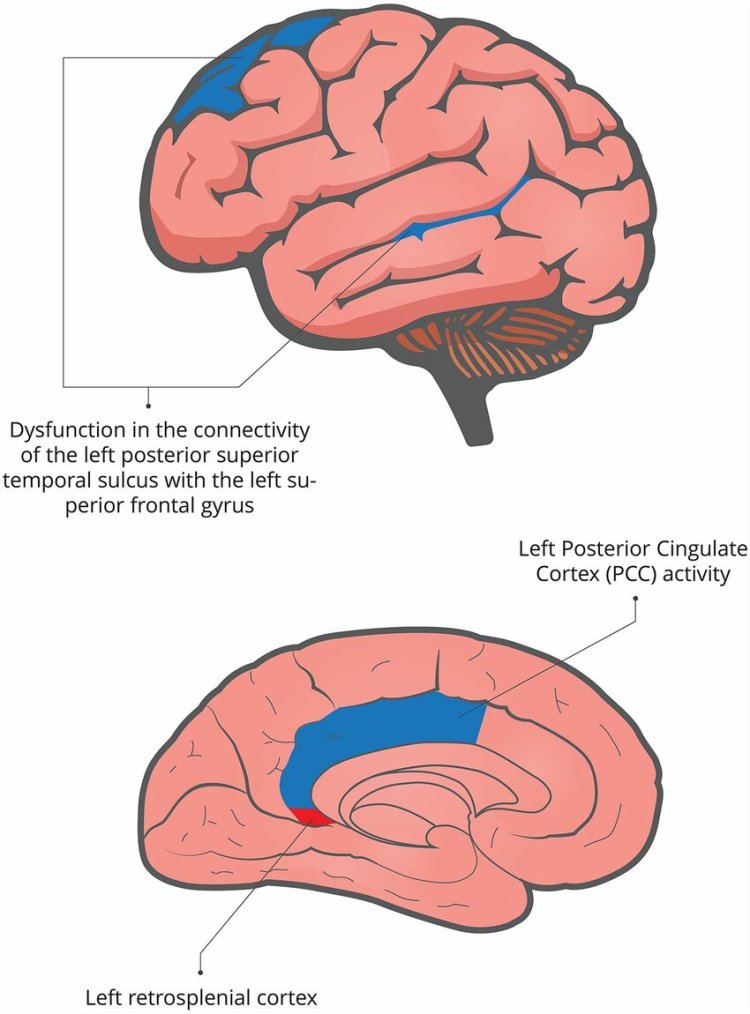

This has been done with patients with Capras syndrome. The results are complicated, but here’s the jist. Humans have two systems for recognizing familiar people. The first system, generally controlled by the left hemisphere, uses visual input; the person looks like your spouse, so they probably are. This makes sense; its how computer face scanning works. And the system has some flexibility. Think about it: your spouse gets a haircut or a new outfit, so they don’t look exactly like your last stored image of them. Do you still recognize them? You do, because your brain does some fast calculations and determines that the person you see right now is a 93% match with your stored image of them. Plus, there is context; what are the chances that someone who resembles your spouse but isn’t would walk into your home, say “Honey, I’m home,” and then see what’s in the fridge?

But we have a complimentary system for recognizing this person that comes out of the right hemisphere. In addition to the way they look, we have associations, memories, and reactions to this person. You two have a history. You have feelings of affection, protectiveness, and memories of shared experiences. These also kick in and help you identify them. But in some cases, something disrupts the right hemispheric recognition system. This means your spouse looks right but doesn’t feel right; all those memories and associations are not being applied to the person standing in front of you.

But that isn’t enough to explain Capgras syndrome. Think about it; you are looking at your spouse, and they look right, but they don’t feel right. It would be strange, almost dreamlike, probably disturbing; its them, but at the same time, it isn’t. How would you react? If it were me, I’d think that something was wrong with me. Maybe I’m having a stroke or a migraine aura or who knows what, but I better have them drive me to the nearest emergency room. So what’s happening?

Underlying Neuropsychological Mechanisms

It turns out that in order for Capgras to occur, there has to be a problem with another system of the brain. Somewhere in our frontal lobes, there is a kind of probability calculator. Its not as good as an advanced computer, but it generally works pretty well even if we aren’t conscious of operating. Humans do some pretty amazing things that we don’t think about much. Ever play baseball? You are in the outfield, and the batter hits the ball, and it arcs out to center field. With no conscious thought, you look at the arc of the ball and instantly calculate its trajectory and run,not to where it is at the moment, but to where its going to end up. Or you are in your car heading for an intersection and the light turns yellow. Do you have enough time to make it before it turns red? You make an immediate decision and either hit the brakes or the accelerator, and you are usually, but not always, right. That’s your brain’s probability calculator at work.

But in cases of Capgras, the brain takes a double hit. The right hemispheric recognition system that uses emotion and memory is disrupted, and the familiar person feels wrong. So what are the possible explanations for this feeling? Here are a couple:

- My brain is malfunctioning; maybe someone slipped something into my drink at Buffalo Wild Wings, where I stopped on the way home, or maybe I’m having a brain aneurysm

- My spouse has been kidnapped and replaced with someone who looks almost exactly like them, maybe a clone or an alien replicant

Obviously, explanation 1 is far more likely. So why do people with Capgras syndrome so readily believe that 2 is the more likely explanation?

The current theory about why this delusion develops is that due to any number of causes, the brain of the Capgras sufferer takes a double hit. First, something interferes with the recognition system I mentioned earlier; this has been referred to as an anomalous experience, in this case the lack of the expected emotional response to a familiar person. The second is a disruption of certain aspects of reasoning and problem solving, in this case related to probability. Put simply, the familiar person feels wrong, and the Capgras sufferer jumps to an improbable conclusion. But this model has some limitations. Even if the brain has been damaged or affected in some way, why would the Capgras sufferer jump to the conclusion that a person has been replaced? After all, even if you can’t estimate probabilities well (for example, something is wrong with the way I am perceiving things vs. my spouse has been kidnapped and replaced by an exact duplicate), wouldn’t you be just as likely to accept the more probable explanation?

Current research suggests that the development of any delusion is caused by a complex interplay between neurological factors, personal predispositions, and cultural beliefs. The idea is that the Capgras sufferer already has a tendency to believe that things are not as they seem, and this tendency is part of the mix. Additionally, they fit this tendency into beliefs that have some support in the broader culture. Just to give a few examples, there are plenty of novels and movies that use the ideas of cloning, shapeshifting, and alien abduction as part of their plots. If someone had the same neurological damage to the recognition system 500 years ago, they wouldn’t be thinking about cloning because they would never have heard of it. I’m guessing they would claim that the person who looks like their spouse was actually the devil or a ghost.

Delusional Thinking in Everyday Life

To be clear, these mechanisms are not unique to those with Capgras syndrome. You can see these tendencies at work every day in conspiracy theorists. One example I saw back during the worst of the Covid pandemic was related to the vaccines. There were plenty of people who refused the vaccine because of the belief that it contained nanobots, placed there by the government to track their movements. How likely was that? Have you read any articles or seen any news that such nanobots exist and could be used for this purpose? Anything is possible, but how likely is it? And even if it were true, millions of people were vaccinated; you’d need an incredibly complicated monitoring system to make any use of the amount of data collected in this manner. Personally, I was struck by one comment on this belief posted on social media. The poster said, “Dude, they don’t need nanobots; you already have a cell phone.” That seems obvious; why go to the trouble of engineering microscopic robots and slipping them into a vaccine to monitor people when you could just track their phone and monitor their actual comments and beliefs? I’m guessing that this idea is driven by pre-existing beliefs that things are not as they appear and that the government is malevolent in ways most people don’t realize. And as an added reinforcer for this belief, aren’t you smart for realizing this when so many others do not? This is sometimes referred to as motivated reasoning.

I’ve personally seen one case of this disorder up close and personal. But before I continue, I want to be clear about something. As a psychologist, I have to protect the identity of the people I treat or assess, unless the cases are a matter of public record. For example, if I’m on local TV testifying about an identified defendant at a public trial, there’s not much point in disguising their identity. But in most other case examples I may include in this post and in the future, I’ll be disguising their identities. In some cases, I’ll be using a technique called hybridizing, where the identities of two or more patients or evaluees are combined. But the underlying symptoms are described accurately and not changed for dramatic effect.

About ten years ago, I received a call from a defense attorney in the northern part of New Hampshire about a perplexing case. It followed the general outline of Capgras syndrome. An older woman had attacked her husband of many years, insisting that it wasn’t him and that he had done something to her spouse. The police were called, and she was arrested. The police quickly figured out that she was unwell and had her evaluated at a local hospital. Although the doctors agreed that she was delusional, she didn’t seem dangerous to anyone but her husband. She was briefly jailed and then arraigned in court. The court, defense attorney, and prosecutor didn’t want her in jail and thought psychiatric hospitalization was the way to go. But the defendant was uncooperative and refused hospitalization; the only place to hold her was in jail. It got worse from there; she stopped talking to her attorney because she had been replaced like her husband and she refused to read correspondence from the court because everyone in the court had also been replaced.

They sent me up to the jail to evaluate her because they needed someone to sign off on involuntary commitment. She was willing to speak to me initially because I was unfamiliar to her and hadn’t been replaced. Her delusions were clearly evident

There was some kind of plot involving her husband, and all the lawyers and the court were involved, although she was still trying to figure out why. After about 20 minutes, she began to become suspicious of me; what was my role in all this and who sent me? Once this happened, she refused to talk to me anymore, but I had what I needed. I took the stand, gave the court a quick overview of Capgras syndrome, and offered my opinion that she needed to be in a hospital. The court concurred, and she was taken to a psychiatric hospital in Boston. The last I heard, she had been treated with antipsychotic medicine, and her delusions had almost, but not completely, remitted.

Variations on the Capgras Theme: The Delusional Misidentification Syndromes

Capgras syndrome is classified with a number of other related disorders, sometimes referred to as the delusional misidentification syndromes. These include:

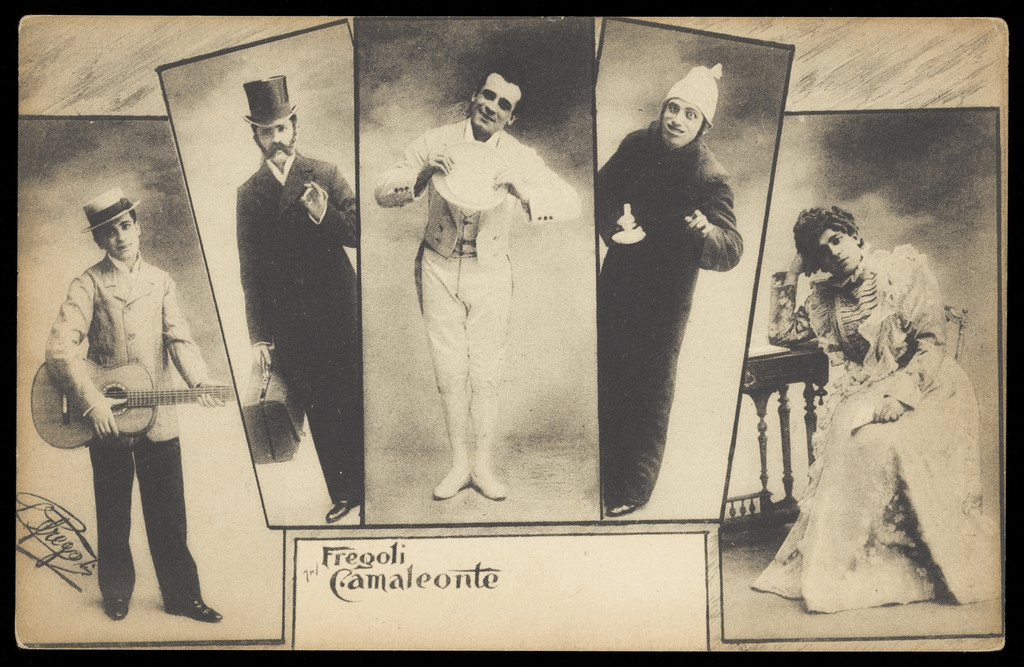

- Fregoli Syndrome: This occurs when the patient believes that any number of people they encounter are actually the same person. One case example involves a man who met a woman on Facebook; he wanted to meet with her and possibly start a relationship, but she was not open to this. He subsequently became convinced that any other women who contacted him were actually the original woman; she was using a special face cream to alter her appearance, and he was convinced she wanted to be in a relationship with her. This case also has features of what has sometimes been called erotomania, but that’s a topic for another post. This syndrome was named after Leopldo Fregoli, a renowned quick-change artist in the 1890s.

- Intermetamorphosis: The belief that familiar people can swap identities with each other or with strangers while maintaining their original physical appearance.

- Syndrome of Subjective Doubles: The belief that there is a doppelgänger or double of oneself carrying out independent actions.

- Mirrored-self Misidentification: The belief that one’s reflection in a mirror is another person.

- Reduplicative Paramnesia: The belief that a familiar person, place, object, or body part has been duplicated.

- Cotard’s Syndrome: The belief that one is dead, does not exist, or has lost internal organs.

- Syndrome of Delusional Companions: The belief that inanimate objects are sentient beings.

- Clinical Lycanthropy: The belief that one is turning into or has turned into an animal.

These variations on a theme are fascinating and raise questions about the workings of the mind. In future posts, I’ll be discussing other unusual psychiatric disorders; stay tuned, and send me any questions you might have.

Discover more from Wandering Shrink (Samurai Shrink)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.